By Annie Stuart, Contributing Writer, interviewing Scott R. Lambert, MD, David A. Plager, MD, and M. Edward Wilson Jr., MD

Download PDF

At one time, “The possibility of restoring the vision in an eye with a congenital unilateral cataract was considered hopeless, and surgery was thought a lost cause,” said Scott R. Lambert, MD, at Stanford University Medical Center in Palo Alto, Calif. “But by learning how to optimize cataract surgery, optical correction, and patching therapy, we have shown it is possible to achieve near-normal vision in many of these patients.”

With publication of its 5-year results, the Infant Aphakia Treatment Study (IATS) helped illuminate the way forward for these children.1 Three of its steering committee investigators review key lessons learned and how they are being translated into clinical practice.

|

|

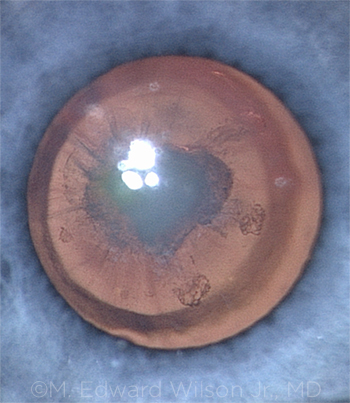

ONGOING STUDY. The IATS involved infants with unilateral congenital cataracts (shown here) who had surgery at 1 to 6 months. Follow-up will extend to 10 years.

|

Key IATS Recommendations

Here are the main messages the investigators now try to drive home, said M. Edward Wilson Jr., MD, at the Medical University of South Carolina’s Storm Eye Institute in Charleston.

Contacts preferred. “If possible, leave babies [who are] operated on in the first 7 months of life aphakic and use a contact lens, with the plan to implant an intraocular lens [IOL] a few years later,” Dr. Wilson said.

“We didn’t conclude that physicians should never use an IOL in a baby,” he said, but rather, that beginning with a contact lens entails “a less-traumatic surgery with fewer reoperations needed” later on. “Also, when the implant is placed later in childhood, we can better predict the growth of the eye and decide on an IOL power with more accuracy than we can with a very small infant.”

Exceptions to the rule. Even so, an IOL might be better for families who have a developmentally delayed child, live a long distance from the doctor, or are expected to have difficulty caring for the contact lenses, said David A. Plager, MD, at Indiana University in Indianapolis. In these cases, infants might otherwise experience significant periods of uncorrected aphakia.

When to operate. “There is some evidence that doing cataract surgery in the first month of life may increase the chances of secondary glaucoma in eyes that are microphthalmic,” said Dr. Wilson. “That’s why we now tend to wait until the 4- to 8-week period to do surgery, even if the cataract is identified on the day of birth.” This also gives the baby time to grow and strengthen, he added, making anesthesia safer and usually preventing a hospital stay. But given the risk of amblyopia in these babies, he said, it’s also important to not wait too long.

Parsing the Choices for Parents

At first blush, parents tend to prefer IOLs because they don’t have to deal with handling contact lenses, said Dr. Plager. “But we help them weigh this convenience against the potential disadvantages.”

Timing. The first thing Dr. Wilson tells parents is that most children will get an IOL at some point, he said. “What we’re really talking about is this: ‘Is it better for your child to have an implant now or later?’ This makes the discussion with the parent a little less anxiety producing.”

If the child is younger than 7 months of age, Dr. Wilson said, “I recommend using the contact lens with a planned secondary implant at about age 5. If the child is older than 7 months, I usually prefer a primary IOL with glasses, which are changed with the growth of the eye.” Dr. Wilson also tells parents that it is possible to switch to an implant at any point.

Invasiveness. Dr. Wilson also explains that the cataract surgery he performs without an implant is done through 2 openings of less than 1 mm each—and thus is much less traumatic to the infant’s eye. “I tell the parents that it is better to clear the cataract early with the least invasive surgery and manage with a contact lens until the eye has grown and is ready for an implant,” he said. “The parents then view the contact lens management in a little different light.”

Reoperations. Dr. Lambert also clearly spells out the risks of reoperation. “In our study, there was a 70% chance of at least 1 reoperation with an IOL,” he said. In contrast, the risk of a second operation was only 20% with contact lenses. However, although the need for reoperation is much higher with IOLs, Dr. Wilson added, studies have also shown that those repeat surgeries are relatively easy to do and do not seem to affect the long-term visual outcome.

Insurance. Contacts are not cosmetic in these babies, said Dr. Plager. “They are medically necessary to develop vision, replacing a body part that was removed. For this reason, insurance companies should cover them, but some don’t, and the lenses can be pricey.”

|

Postoperative Complications

The IATS tracked several postoperative complications, including the following.

Glaucoma risk. How likely are babies to develop glaucoma after cataract surgery? Previous estimates of this postoperative risk came from retrospective studies and varied widely, from as little as 5% to as much as 60% or 70%, Dr. Plager said. The risk of glaucoma at 5 years in the IATS was about 20%. “We don’t fully understand why children develop glaucoma after cataract surgery, although younger children appear to be more at risk,” Dr. Lambert noted.

Are IOLs protective? Some studies have suggested that an IOL may protect against glaucoma. However, they are retrospective in nature and have a strong selection bias, said Dr. Wilson. “In these studies, the eyes with microphthalmia, an immature iris, and poorly dilating pupils—all markers for an immature trabecular meshwork—were the eyes that were operated on the youngest and the ones surgeons tended not to implant. But these are also the eyes most at risk for glaucoma.”

The IATS investigators “did not find that the IOL was protective,” Dr. Plager said. “At 5 years, there were no big differences in glaucoma incidence between the contact lens and IOL groups, and I don’t expect to see any at 10 years.”

Vigilance is essential. The IATS also has shown that new cases of glaucoma can continue to present years after surgery in microphthalmic infant cataract eyes. “We have to be vigilant” about following these children, said Dr. Wilson.

Lens reproliferation. Despite good cortical cleanup after cataract surgery in the first 6 months of life, a few lens epithelial cells always remain, said Dr. Wilson. “When we leave the eye aphakic and use a contact lens, the new material those cells create gets trapped within the capsule and can be cleaned up and removed later when an IOL is placed,” he said. “But when an IOL is placed during the early high-growth stage, the material is likely to not stay sequestered.” Instead, he said, it escapes into the pupillary space, causing lens reproliferation into the visual axis.

Although not unexpected, “the high incidence of visual axis opacification in patients with IOLs was quite striking,” said Dr. Lambert, explaining that it occurred most often in the year after surgery and was 10 times more prevalent in the IOL group.2

No preventive strategies. Unfortunately, there aren’t any successful techniques to prevent visual axis opacification, said Dr. Plager. “Some criticized our study, suggesting that we did not use enough steroids, but this is not an inflammatory problem.” Additionally, investigators were given latitude on its use, and babies who received more steroids had the same rate of visual opacification.

Two preventive measures that have been suggested involve injecting mitomycin C (MMC) to kill cells or employing the bag-in-the-lens (BIL) technique with the Tassignon IOL (Morcher). However, both are problematic.

Using MMC “might help, but it would probably cause all kinds of other damage as well,” Dr. Plager said. And the Tassignon IOL is not currently available in the United States. (For more on this IOL and the BIL procedure, see aao.org/clinical-video/bag-in-the-lens-cataract-surgery.)

Research Update: Artisan Aphakia Lens

Developed in the Netherlands about 30 years ago, the Artisan Aphakia IOL (Ophtec) has been used in Europe ever since, and surgeons are quite happy with it, said Dr. Plager. Candidates include children who can’t have a posterior chamber lens, he said, such as those who’ve experienced trauma or lens subluxation from Marfan syndrome.

Another group of potential candidates: children with unilateral congenital cataracts. “In patients with aphakia and inadequate or no capsular support, many surgeons have been looking for an alternative to transscleral suturing of lenses in growing eyes or IOLs where the haptics are externalized and fixed in a scleral tunnel,” said Dr. Wilson. “We haven’t been pleased with angle-supported anterior chamber lenses in growing eyes where sizing has been a problem. So the Artisan Aphakia IOL and its iris-claw attachment is an alternative to those 2 options.”

The Artisan Aphakia lens has been studied in the United States for the past few years, said Dr. Plager, but results have not yet been published. “We have nearly 200 pediatric patients using this lens in the United States,” said Dr. Wilson. “A few of my patients have reached the 4-year point, and we’re submitting those data to the FDA. In my experience, the patients do very well with it. I’ve been pleased with its stability and safety.”

|

Improving Visual Outcomes

Congenital cataracts differ from developmental cataracts in that the latter tend to have much better outcomes, said Dr. Wilson. That’s because eyes with developmental cataracts have had relatively normal early experience, he noted. However, the following factors can improve the visual outcomes of infants with congenital cataracts.

Reducing complications. In the IATS, the median visual acuity was the same for both the contact lens and IOL cohorts. However, at 4.5 years, twice as many treated eyes in the contact lens cohort had better than 20/40 acuity. One reason may be that eyes left aphakic and treated with a contact lens didn’t experience as many immediate postoperative complications as those that underwent IOL implantation, Dr. Lambert said.

Correcting refractive error. Another reason for better results in the contact lens group is that you can adjust as the child grows and the refractive error changes, which happens rapidly in the first few years, said Dr. Plager. “You can change the contact lens with a snap of the finger.”

In contrast, when you put in an IOL, you are making an educated guess about the lens power that will be needed when the child is fully grown, he said. Despite the IATS investigators’ efforts on this front, some of the children who received IOLs “became very nearsighted and may need a new lens implant or a refractive surgery like LASIK,” Dr. Plager said.

Patching. Another variable with unilateral cataracts is patching, which may reduce the incidence of strabismus, said Dr. Wilson. “With IATS, we patched 1 hour per day per month of age—but patched no more than half the child’s waking hours over the long term.” The goals are to patch enough to allow maximum vision development without compromising the child’s ability to become binocular and to gradually reduce patching, he said. “The unanswered question is, When can you stop? It appears that a lot of patching may interfere with the development of stereopsis in some children.”3

Compliance. Clearly, compliance also makes a difference in visual outcomes, said Dr. Wilson. “Prognosis is better when parents comply with patching and use the glasses and contacts properly so there isn’t a lot of time when the aphakia is uncorrected.”

This is particularly true in children who were left aphakic. Children who have received IOLs have a little more leeway, as the IOL provides partial refractive correction and glasses are used to fine-tune the correction.

___________________________

1 Lambert SR et al. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014;132(6):676-682.

2 Plager DA et al. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014;158(5):892-898.

3 Lambert SR et al. Eye (Lond). 2016;30(9):1221-1228.

___________________________

Dr. Lambert is professor of ophthalmology at the Stanford University Medical Center in Palo Alto, Calif. Relevant financial disclosures: National Eye Institute: S.

Dr. Plager is professor of ophthalmology and director of the Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus Service at Indiana University School of Medicine in Indianapolis. Relevant financial disclosures: None. Dr. Wilson is the N. Edgar Miles Professor of Ophthalmology and Pediatrics at the Medical University of South Carolina’s Storm Eye Institute in Charleston. Relevant financial disclosures: None.

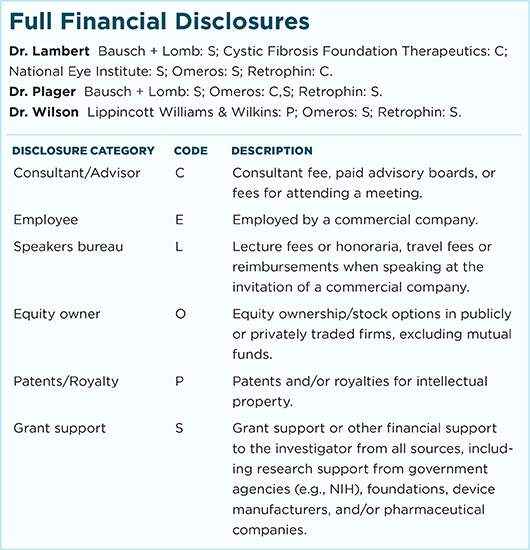

For full disclosures and the disclosure key, see below.