By Brian C. K. AU, MD, and Charlise Gunderson, MD

Edited by Thomas A. Oetting, MD

This article is from July/August 2007 and may contain outdated material.

Every summer, the Bonk family piles into their car for a major road trip. This year they had decided to explore Arizona, and Billy,* the 12-year-old son, was anticipating the journey with even more trepidation than usual. Not only would he be sharing the backseat with his two younger sisters, aged nine and six, but he also was nursing two sore eyes. The day before they were due to set off, his mother brought him to the ER where an ophthalmology resident had a look at him. His uncorrected visual acuity was 20/70 in the right eye and 20/200 in the left, but his pupils, extraocular movements, confrontational visual fields, IOP and dilated fundus exams were unremarkable. However, subtle, bilateral, multifocal, subepithelial corneal infiltrates with minimal fluorescein staining and surrounding stromal edema were documented. The resident diagnosed conjunctivitis, and prescribed antibiotics.

We get a look. Three weeks and 1,800 miles later, the Bonks were back home and Billy’s eyes still hurt. His mother brought him back to the ER and he was referred to our pediatric ophthalmology clinic.

When we saw Billy, he had bilateral blurry vision, red eyes, foreign body sensation and photophobia. He told us that he had suffered moderate pain for several weeks. No alleviating or exacerbating factors were elicited. He denied any itching, discharge or photopsias. His medical, surgical, ocular, family and birth histories all seemed unremarkable. His immunizations were up to date, he had no known drug allergies and, in any event, was not on any systemic or ocular medications. His BCVA was 20/60 in the right eye and 20/40 in the left, and on slit-lamp exam a mild follicular response was noted on the palpebral conjunctiva bilaterally. The bulbar conjunctivae were mildly injected, and we noted superior micropannus on both corneas. Finally, there were 2+ cells and flare bilaterally. The lens and anterior vitreous of both eyes were normal. No preauricular lymphadenopathy was noted.

|

|

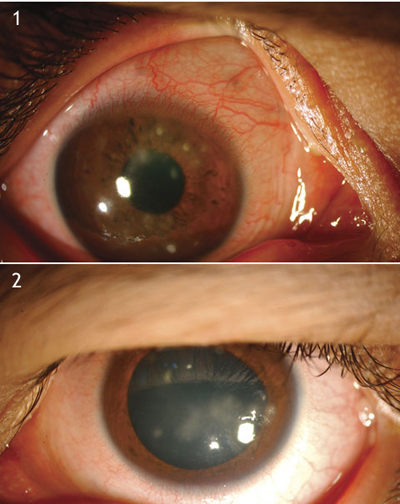

Billy's Double Trouble: Despite three weeks of antibiotics, the pain persisted in both his right (1) and left (2) eyes, particularly in bright light. "Things look blurry, " he told us, "and it feels like there's grit in my eyes."

|

What's Your Diagnosis?

We make a definitive diagnosis. On further history, the patient denied any recent upper respiratory symptoms, seasonal allergies, new medications or eyedrops, rashes, gastrointestinal symptoms, eye trauma or contact lens use. However, Billy’s mother told us that he had suffered multiple bouts of knee and ankle pain, leg swelling, dysuria and even hematuria when he was younger. After consultation and evaluation by a pediatric rheumatologist and further laboratory workup, we diagnosed Billy with reactive arthritis (formerly Reiter’s syndrome) and started him on oral steroids. We treated him for reactive arthritis–associated keratoconjunctivitis with Maxitrol (a combination of neomycin, polymixin B and dexamethasone) three times a day and Hyoscine (scopolamine) twice a day in both eyes, and scheduled a one-week follow-up appointment. Incidentally, he was negative for HLA B27.

Clinical Findings

Ocular findings of the condition. Reactive arthritis is classically associated with the triad of conjunctivitis, arthritis and nongonococcal urethritis, though it is rare for a patient to present with all three signs. Reactive arthritis occurs most frequently in young males. The most common initial ocular manifestation of reactive arthritis is conjunctivitis.1 It is often associated with a mucoid discharge but without preauricular lymphadenopathy. A punctate epithelial keratitis can sometimes occur with pleomorphic, multifocal subepithelial infiltrates of the midperipheral cornea as well as micropannus.2 An acute anterior nongranulomatous uveitis may also occur and occasionally can spill over into the anterior vitreous. These findings, when present, are often bilateral but may be asymmetric. Secondary open-angle glaucoma due to anterior chamber inflammation, episcleritis or scleritis, and multifocal choroiditis are possible but uncommon.

Systemic findings of the condition. These include fever, weight loss and skin and nail changes, such as subungual pustules and hyperkeratosis. Circinate balanitis on the glans penis in men, cervicitis in women and painless oral mucocutaneous lesions in both may occur. A characteristic dermatologic finding is keratoderma blennorrhagia, consisting of papules, vesicles or pustules located on the palms or the soles of the feet. The arthritis is seen in the knees, ankles, feet and wrists and tends to be migratory, asymmetric and sometimes recurrent. A permanent disability, mainly due to musculoskeletal causes, occurs in about 20 percent of patients.2

Etiology. Laboratory tests such as the HLA-B27 antigen can support a diagnosis of reactive arthritis, as more than 75 percent of patients with the condition are HLA-B27 positive.3 Antecedent gastrointestinal infection from bacteria like Campylobacter, Salmonella, Shigella and Yersinia may lead to subsequent development of reactive arthritis. The role of Chlamydia in genitourinary infections as an etiologic factor for the development of reactive arthritis remains a topic of debate.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of peripheral corneal opacities include viral (herpes simplex virus, adenovirus), bacterial (Chlamydia, Neisseria) and allergic (atopic, vernal) keratoconjunctivitis; Staphylococcus-related marginal keratitis; phlyctenular keratoconjunctivitis; rosacea keratitis; and peripheral ulcerative keratitis, often secondary to collagen vascular diseases.

Viral conjunctivitis is often preceded by an upper respiratory infection, with burning, foreign body sensation, conjunctival injection with a follicular response, mucoserous discharge and preauricular lymphadenopathy. Visual acuity is usually unchanged or minimally affected. Herpes simplex keratoconjunctivitis is characterized by decreased vision, decreased corneal sensitivity, eye pain, burning, foreign body sensation, preauricular lymphadenopathy, and occasionally concurrent periocular skin vesicles. Epidemic keratoconjunctivitis caused by adenovirus types 8 and 19 can cause subepithelial infiltrates that can scar over and, if over the visual axis, can significantly affect vision.

Bacterial conjunctivitis is characterized by decreased vision, foreign body sensation, mucopurulent discharge, and conjunctival injection with a papillary response, with the exception of chlamydial infections, which demonstrate a follicular response especially in the tarsal conjunctiva of the upper eyelid. Gonococcal hyperacute conjunctivitis, often with marked papillae, frank purulent discharge, preauricular lymphadenopathy and eyelid swelling, is truly an ophthalmologic emergency and necessitates immediate treatment with intravenous and topical antibiotics, since Neisseria can penetrate the cornea and lead to perforation.

Patients with allergic conjunctivitis complain of intense itching and watery discharge, and they usually have a history of seasonal or perennial allergies. Signs include conjunctival chemosis with a papillary reaction and sometimes periocular swelling. Those with atopic keratoconjunctivitis also have thick ropy discharge and a history of atopy. Corneal “shield” ulcers and raised white dots near the limbus, known as Horner-Trantas dots, are characteristic.

Staphylococcal marginal keratitis is a hypersensitivity reaction to Staphylococcus antigens and is associated with chronic blepharitis. Focal, noninfectious subepithelial infiltrates occur, as a result of the host’s antibody response, on the peripheral cornea but are separated from the limbus by a peripheral clear zone. Because of the association with chronic blepharitis, these infiltrates are usually found at the 2, 4, 8 and 10 o’clock positions of the cornea. Lesions usually do not stain with fluorescein, and the eye is typically quiet.

In contrast, phlyctenular keratoconjunctivitis is characterized by focal, sterile infiltrates on the bulbar conjunctiva, the limbus or the cornea without a peripheral clear zone. Since the overlying epithelium can break down, these infiltrates do stain with fluorescein. Classically, phlyctenulosis represents a type IV hypersensitivity reaction to tuberculosis, but can also represent hypersensitivity to Staphylococci or certain fungi and viruses.

Rosacea is associated with dysfunction of the sebaceous glands of the skin, face, and eyelids. Excessive sebum secretion from the eyelids causes a chronic blepharitis, which can evolve into a chronic conjunctivitis, marginal corneal infiltrates, sterile ulceration, episcleritis and even iridocyclitis. Chronic rosacea keratitis can lead to corneal neovascularization and scarring.

Peripheral ulcerative keratitis is associated with a myriad of autoimmune and collagen vascular diseases, such as Sjögren’s syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, granulomatosis with polyangiitis (formerly Wegener’s granulomatosis), polyarteritis nodosa, systemic lupus erythematosis, scleroderma, relapsing poly- chondritis, inflammatory bowel disease and Behçet’s disease, to name a few. Ocular signs include conjunctival injection, peripheral corneal infiltrates, and stromal thinning or melting.

Management

Treatment of reactive arthritis–associated keratoconjunctivitis consists of frequent topical steroids, cycloplegia if there is significant anterior chamber inflammation, and topical antibiotics for any associated corneal epithelial disease to prevent secondary infections. Close follow-up and comanagement of the systemic disease with a rheumatologist or an internist is paramount.

Appropriately managed, the corneal lesions can resolve in a matter of months without residual scarring or corneal vascularization.

Billy’s progress. After several weeks of treatment with frequent topical steroids and cycloplegics, Billy’s BCVA improved to 20/20 in both eyes, his anterior chambers were quiet, and the subepithelial infiltrates were resolving bilaterally.

___________________________

*Patient name is fictitious.

___________________________

1 Krachmer, J. H. et al. Cornea, 2nd ed. (Philadelphia: Elsevier Mosby, 2005).

2 Lee, D. A. et al. Ophthalmology 1986;93:350–356.

3 Brewerton, D. A. et al. Lancet 1974;1(7864):956–958.

___________________________

Dr. Au is a third-year resident and Dr. Gunderson is director of pediatric ophthalmology; both are at the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston.