By Leslie Burling, Contributing Writer, interviewing Penny A. Asbell, MD, MBA, Elisabeth J. Cohen, MD, and Sonal S. Tuli, MD

Download PDF

Herpesviruses cause a multitude of miseries for the eye, affecting not only the cornea but also the ocular adnexa, uvea, and retina. For the cornea in particular, the herpes simplex virus (HSV) is the most common cause of epithelial keratitis, and the virus can also produce more serious consequences, including stromal keratitis and corneal perforation. The varicella-zoster virus (VZV)—another member of the herpesvirus group—is the causative agent for herpes zoster ophthalmicus (HZO), which includes neurotrophic keratitis among its many manifestations.

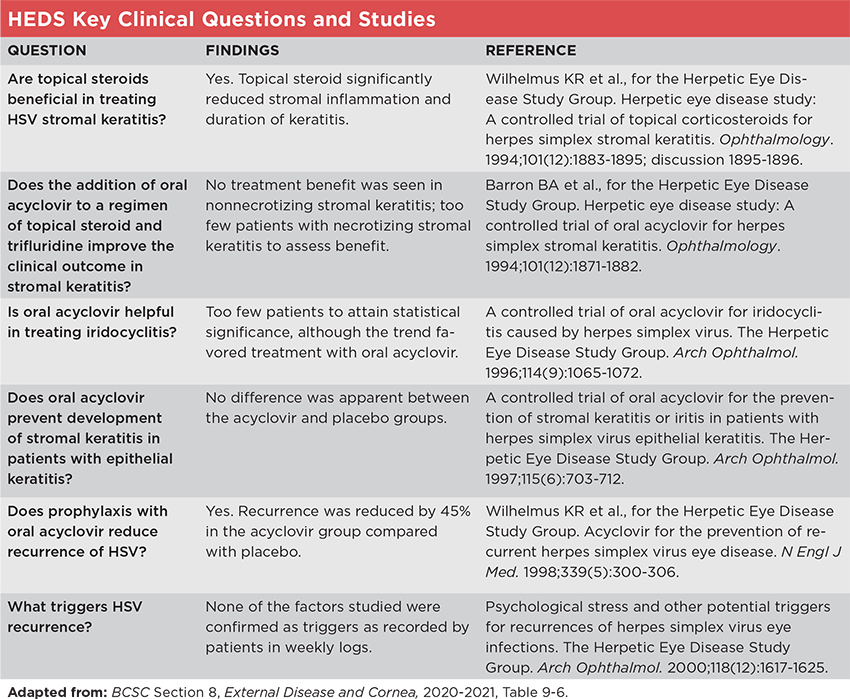

The Herpetic Eye Disease Study (HEDS), a series of randomized placebo-controlled clinical trials initiated in 1989, assessed the optimal treatment and prophylaxis for HSV keratitis or iridocyclitis, as well as factors in disease recurrence. HEDS changed treatment paradigms and is still considered the gold standard in the management of anterior segment HSV disease.1,2 The Zoster Eye Disease Study (ZEDS), now underway, has the potential to make a similar impact on management of VZV eye disease, notably HZO.

HEDS: Important Questions

Each of the studies within HEDS focused on a key clinical question (see “HEDS Key Clinical Questions and Studies,” below). The answers to all of these questions have helped to guide treatment—as important in demonstrating what measures do not work as in confirming those that do. But the following two questions have had the strongest continuing effect on practice, said Sonal S. Tuli, MD, at the University of Florida in Gainesville.

Question: Are topical steroids beneficial in treating HSV stromal keratitis? Before HEDS, the use of corticosteroids for HSV keratitis was controversial, with some authors arguing that the availability of ophthalmic topical steroids had led to more frequent and severe keratitis. Prior studies were hampered by lack of effective antiviral drugs and the inclusion of cases of epithelial keratitis.3

To resolve this question, HEDS enrolled 106 patients with active HSV stromal keratitis who had not received corticosteroids within 10 days before enrollment. They were randomized to receive placebo or a tapering regimen of topical prednisolone phosphate for 10 weeks, and all participants also received antiviral eye drops (trifluridine). They were followed every other week for six weeks and again at six months after randomization.4

Answer: Yes. HEDS investigators found that patients who received prednisolone phosphate drops experienced “fewer treatment failures and faster resolution of stromal keratitis,” said Dr. Tuli. “In fact, a 68% reduction in disease persistence and progression was observed during this study,” she added. However, six months after the study, no significant difference was seen between the groups, “but this may be related to a much more rapid taper of steroids than is currently the practice,” said Dr. Tuli.4

Question: Does prophylaxis with oral acyclovir reduce recurrence of HSV? The virus is known to persist in a latent form, often in the trigeminal nerve, which can lead to repeated reactivation of ocular disease. Prophylactic use of antivirals had been shown to reduce recurrence in orofacial HSV but had not been tested in a randomized controlled trial of HSV keratitis.5

The HEDS investigators enrolled 703 participants who had experienced an episode of anterior segment HSV in the prior 12 months but not within 30 days before the study. Participants were randomized to placebo or 400 mg of oral acyclovir twice daily for 12 months and remained on the assigned treatment regardless of recurrence (those who had a recurrence were treated with topical antivirals at the physician’s discretion).5

Answer: Yes. The researchers found that recurrence was decreased by 45% in the acyclovir group compared with the placebo group.5 They considered this reduction of greatest benefit in stromal keratitis, which causes the most severe visual problems. The magnitude of absolute benefit was the greatest among patients with the highest number of prior episodes of ocular HSV disease.2 However, in the six-month observation phase after treatment ceased, there was no significant difference in recurrence between the groups,5 suggesting that there is no rebound in HSV infections when acyclovir is stopped, said Penny A. Asbell, MD, MBA, at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center in Memphis. Dr. Tuli said that it also indicates that the protection only lasts as long as the prophylaxis is continued.

Treatment Updates

In the quarter-century since these two HEDS trials were published, new drugs have become available, and additional research has revealed some nuances for better tailoring the treatment regimens.

New therapeutic options. “At the time of HEDS, trifluridine was the most widely prescribed topical antiviral agent for treatment of HSV keratitis in the United States,” said Dr. Asbell. “However, side effects such as punctate keratopathy, allergic conjunctivitis, and ocular surface toxicity have led to decline in its use as new topical antivirals have become available.” Dr. Asbell noted that these newer antivirals—ganciclovir 0.15% gel and acyclovir 3% ointment [not available in the United States]—are highly specific to virus-infected cells and thus less likely to harm host cells. Topical acyclovir and ganciclovir are reported to have similar efficacy, although ganciclovir was better tolerated.2

Newer oral antiviral agents have also been introduced since HEDS. According to Dr. Asbell, famciclovir and valacyclovir (a prodrug of acyclovir) have better bioavailability and less burdensome dosing regimens than oral acyclovir. However, she said, the optimal regimen for ocular HSV keratitis has not been established for these drugs.

Tailoring HSV treatment. For epithelial keratitis, antiviral treatment alone is recommended, and topical steroids should be avoided.1 Dr. Tuli said that cornea specialists are split on whether to use topical or oral antiviral agents. “You need to play it by ear. There is not a one-size-fits-all solution.”

For example, oral agents may be preferable for patients with preexisting ocular surface disease, those who have hand tremors or arthritis, people who wear contact lenses, or children who flinch at eye drops. Topicals are preferred for patients with renal impairment, individuals taking systemic immunosuppressants, and women who are pregnant or breastfeeding.1

Stromal HSV: combined therapy. The HEDS trial of corticosteroids for stromal keratitis used topical formulations for both the steroid and antiviral components.4 However, the Academy’s 2014 clinical guidelines recommend oral antivirals for most patients because of concerns over ocular surface toxicity with trifluridine and inadequate corneal penetration with both trifluridine and topical ganciclovir (topical acyclovir is not FDA approved).1 “Oral antivirals are also preferred since stromal keratitis is an immune-mediated response, and the goal of antivirals is to prevent recurrence in the trigeminal ganglion while on topical steroids rather than to treat active viral keratitis,” said Dr. Tuli.

As with epithelial keratitis treatment, however, cornea experts differ in their choice of topical versus oral antiviral therapy for stromal keratitis. Dr. Asbellsaid she “generally recommends starting a combination of topical steroid (for instance, prednisolone 1% or difluprednate 0.05%) used about four times a day together with topical ganciclovir gel 0.15% five times a day.” She added that she tapers the topical steroid and antiviral together, ideally maintaining the antiviral coverage until the steroid is discontinued. In contrast, Dr. Tuli uses oral antiviral instead of topical agents to reduce ocular surface toxicity, and she tries to gradually reduce topical steroids to the lowest dose possible to maintain quiescence, knowing that some patients with stromal HSV will require indefinite use of topical steroids.

Duration of steroid treatment. During the 10-week study period in HEDS, the steroid-treated group did significantly better than the placebo group; but in the six-week observation period after treatment cessation, failure rates rose dramatically.4 Thus, a longer steroid regimen is now recommended, and “the treatment course should be titrated empirically depending on clinical response.”1

Reducing recurrence. “The more episodes of HSV you have, the more likely you are to have another—the odds are about 50%,” said Dr. Tuli. “There is also evidence suggesting that short intervals between attacks tend to be correlated with short intervals between future attacks.” She noted that those who are immunocompromised or who have atopy, atopic dermatitis, or asthma are also more likely to experience recurrences.

“One of the most valuable lessons from HEDS is that an oral antiviral prevents recurrences when taken long-term,” Dr. Tuli said. “HEDS showed that if you treat patients for a year, there are fewer recurrences during that year. But the moment you stop, the risk goes back exactly to where it was before you started prophylactic treatment.

“Some of my patients have been taking oral acyclovir for 20 or more years,” said Dr. Tuli. “They have tolerated it well, and it has significantly reduced their number of HSV recurrences.” She noted a few caveats: “Since valacyclovir is metabolized in the liver, I recommend checking liver function tests yearly. Also, since antivirals are excreted through the kidney, a basic metabolic panel is recommended yearly to prevent toxicity in case of decreased renal function.”

Corneal procedures in HSV patients. Surgical trauma coupled with local immunosuppression by perioperative corticosteroids increases the likelihood of HSV recurrence. Thus, performing elective eye surgery on a patient with a history of HSV ocular disease is typically contraindicated.2 “All patients with a history of ocular HSV infection should be well informed regarding the risk of HSV reactivation following LASIK or PRK,” Dr. Asbell emphasized. However, if surgery is performed, she said, “perioperative and postoperative antiviral therapy should be given.”

Dr. Asbell added that “two procedures developed since HEDS—corneal cross-linking and excimer refractive surgery—may also put patients at risk for ocular HSV disease resulting from exposure to the ultraviolet light.”

Dr. Tuli said that some of her patients have had phototherapeutic keratectomy for HSV scarring. “I usually put such patients on therapeutic doses of oral antivirals starting three to five days before the surgery and continuing for at least two to three weeks afterward, followed by prophylactic doses long-term.”

ZEDS: Seeking Evidence

As with HSV, after initial infection, VZV lurks in the nerves and can reactivate after a period of latency due to declining cell mediated immunity. In addition to HZO, VZV can cause the systemic manifestations of shingles and postherpetic neuralgia.6

A survey conducted among ZEDS investigators showed that about half of them treat HZO with prolonged oral antivirals, in addition to topical steroids, and two-thirds believe that approach is effective—despite a lack of good evidence.6 “ZEDS is a unique opportunity to find out if that’s true or not. If it’s true we will have evidence-based standards of care to reduce complications,” said Elisabeth J. Cohen, MD, at NYU Langone Health in New York City, and chair of the ZEDS study.

Dr. Asbell, who is on the ZEDS steering committee, said that “HZO and HSV keratitis are analogous in many ways” and that the classification of keratitis in the HSV guidelines1 is applicable to HZO as well. Dr. Cohen said, “These similarities are the rationale for why we believe that prolonged low-dose suppressive antiviral treatment may have similar benefits in HZO.”

Primary objective. The primary aim of ZEDS is to determine whether suppressive antiviral treatment with oral valacyclovir for 12 months delays the occurrence of specific forms of HZO keratitis and iritis. The researchers are enrolling patients who have had HZO at any time in the past and an episode of active keratitis or iritis in the year prior to enrollment. They will be assessed at 12 months as the primary endpoint and at 18 months as the secondary endpoint.7

“The results could be huge,” said Dr. Cohen. “We have seen that HSV ophthalmic outcomes have really been improved with prolonged suppressive antiviral treatment, and we have the same potential to achieve that with HZO.”

Implications beyond the eye. As a secondary objective, the ZEDS investigators will assess whether the study drug reduces the incidence or severity of postherpetic neuralgia. If so, said Dr. Cohen, “then our findings would be relevant to HZ in other locations where people, particularly the elderly, develop chronic pain that can ruin the quality of life for the rest of their lives.”

Help needed. Dr. Cohen said that the investigators need support from ophthalmologists in the United States and Canada to refer their HZO patients to one of the 70 centers in the United States or to the nine centers in Canada. Addressing a possible source of hesitancy, she emphasized that it is important for ophthalmologists and potential study participants to know that—regardless of study arm assignment—open-label treatment is available if new or worsening HZO occurs.

A Strong Recommendation

Until the ZEDS results are available, there is something that all doctors can do to reduce the burden of HZO: advocate for vaccination against VZV, Drs. Asbell and Cohen agreed.

Dr. Cohen said, “It is very important for ophthalmologists to take a history about vaccination against zoster and encourage all of their patients ages 50 and over to get vaccinated with the two-dose series of Shingrix,” even if they already received the earlier Zostavax. “It is readily available at chain pharmacies, where pharmacists are well trained to administer the vaccine.”

__________________________

1 White ML, Chodosh J. Herpes Simplex Virus Keratitis: A Treatment Guideline. 2014. aao.org/clinical-statement/herpes-simplex-virus-keratitis-treatment-guideline. Accessed March 15, 2021.

2 Kalezic T et al. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2018;29(4):340-346.

3 Chodosh J. Ophthalmology. 2020;127(Suppl 4):S3-S4.

4 Wilhelmus KR et al. Ophthalmology. 1994;101(12):1883-1896.

5 Herpetic Eye Disease Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(5):300-306.

6 Lo DM et al. Cornea. 2019;38(1):13-17.

7 clinicaltrials.gov, NCT03134196.

__________________________

Dr. Asbell is the Barrett G. Haik Endowed Chair for Ophthalmology and Director of the Hamilton Eye Institute at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center, in Memphis. Financial disclosures: Alcon: C; Allakos: C; Axero: C; BlephEx: C; Contact Lens Association of Ophthalmologists: C; Dompé: C; EyePoint: C; Kala: C; MC2: S; Miotech: S; NIH: S; Novaliq: C; Regeneron: C; Sanofi: C; Santen: C; Senju Pharmaceuticals: C; Shire: C; Sun: C; TopiVert: C.

Dr. Cohen is professor of ophthalmology at NYU Langone Health, in New York City. Financial disclosures: None.

Dr. Tuli is professor and chair in the department of ophthalmology at the University of Florida, Gainesville. Financial disclosures: None.

See the disclosure key at www.aao.org/eyenet/disclosures.