By Reuben Foo, MBBS, Andrew Tsai, MBBS, and Laurence Lim, MBBS, MMed(Ophth), FRCOphth

Edited By: Sharon Fekrat, MD, and Ingrid U. Scott, MD, MPH

Download PDF

Suprachoroidal hemorrhage (SCH) is a rare but potentially devastating complication of intraocular surgery. It is defined as the accumulation of blood within the potential space between the choroid and sclera, with the source of the blood being the long or short posterior ciliary artery.1

SCH occurs less commonly in association with modern techniques of cataract surgery than with glaucoma, vitreoretinal, and penetrating keratoplasty (PK) procedures. The extent of SCH ranges from localized, self-limiting hemorrhages to expulsion of intraocular contents. It is important to recognize this complication early and to manage it expediently.

Risk Factors

Factors that increase the risk for SCH include the following:

Systemic

- Advanced age

- Cardiovascular conditions, including hypertension and peripheral vascular disease

- Medications, including anticoagulation and antiplatelet agents and cardiovascular drugs

Ocular

- High myopia

- Aphakia

- Glaucoma

- Elevated preoperative intraocular pressure (IOP)

- Previous intraocular surgery such as PK or vitrectomy

Intraoperative

- Retrobulbar anesthesia

- Failure to administer ocular compression to reduce IOP before and after retrobulbar anesthesia

- General anesthesia (“bucking” on tube)

- Posterior capsular rupture with vitreous loss

- Elective extracapsular cataract extraction (ECCE)

- Conversion from phacoemulsification to ECCE

- Longer duration of intraocular surgery

Postoperative

- Hypotony

- Valsalva maneuvers, including coughing and straining

Cataract Surgery

The incidence of SCH during cataract surgery has decreased with the evolution of newer techniques. These include the use of topical anesthesia instead of retrobulbar block and the adoption of smaller-incision surgery and self-sealing clear corneal incisions instead of ECCE, with its larger surgical wounds.

The estimated incidence of SCH during cataract surgery reported in the past 25 years is approximately 0.03% to 0.1%,2-4 compared with earlier reports of up to 0.8%1 with older techniques. The majority (up to 50%) of cataract surgery–related SCH occurs during phacoemulsification or nuclear expression or after removal of the nucleus.4,5

Signs. Intraoperative signs of SCH include the following:

- Anterior chamber shallowing

- Loss of the red reflex

- Increased IOP, with firming of the eye

- Wrinkling and bulging of the posterior capsule

- Extrusion of intraocular contents: spontaneous nuclear expression, iris prolapse, and vitreous prolapse

Glaucoma Surgery

The incidence of intraoperative SCH during incisional glaucoma surgery has been reported to be about 0.15%.6 However, glaucoma surgery–related SCH is more likely to occur postoperatively, with an incidence ranging from 1.6% to 6.1%,7,8 than intraoperatively. The later onset is likely due to the possible occurrence of hypotony after glaucoma filtration surgery and postoperative inflammation.

Signs and symptoms. SCH in the postoperative period may include the following signs and symptoms:

- Severe eye pain

- Headache, nausea, and vomiting

- Decreased visual acuity

- Anterior chamber shallowing

- Loss of the red reflex

- Elevated IOP

- Prolapse of vitreous into the anterior chamber

- Choroidal elevation

Vitreoretinal Surgery

The incidence of intraoperative SCH during vitreoretinal surgery has been reported to range from 0.17%9 to 1.9%.10 Risk factors include rhegmatogenous retinal detachment, scleral buckle placement, and the presence of retained lens fragments.

In a 5-year retrospective study by Reibaldi and colleagues, SCH was reported to occur in 0.8% of patients during the postoperative period; and extensive intraoperative photocoagulation was identified as a risk factor.11

Penetrating Keratoplasty

Intraoperative SCH during PK can be attributed to the use of an open-sky technique, which leads to a longer period of intraocular hypotony. The reported incidence ranges from 0.09% to 1.08%.12,13

Preventive Measures

Preoperative steps to reduce the risk of SCH include controlling IOP and—in cooperation with the patient’s other physicians—withholding anticoagulants or antiplatelet agents and managing comorbidities such as hypertension. Also, nonurgent intraocular surgery may be delayed in a patient who has a cough until it resolves.

If peribulbar or retrobulbar anesthesia is used, orbital compression helps to lower the IOP before starting the intraocular surgical procedure.

Postoperative hypotony should be avoided, especially with glaucoma filtration surgeries.

Intraoperative Management

Wound closure. Early detection of SCH is the first step in management. Prompt suture closure of surgical incisions is important to tamponade the bleeding vessels and prevent extrusion of intraocular contents. Prolapsed vitreous or nonviable iris tissue may need to be surgically excised to allow wound closure.

Deepening of the anterior chamber. The anterior chamber can be deepened by injecting either a viscoelastic agent or air into the anterior chamber after repositing any expulsed intraocular contents.

Surgical drainage. The creation of a posterior draining sclerotomy is controversial. Paradoxically, the elevated IOP resulting from SCH may have a tamponading effect against further bleeding, and this effect may be lost when the hemorrhage is drained.

Postoperative Management

Medical management. High IOP is managed with antiglaucoma medications. Topical or oral steroids may be used to control inflammation and promote clot liquefaction. Secondary pain can be managed with topical cycloplegics and oral analgesia.

Secondary surgical drainage. Limited, nonappositional SCHs may not require surgical intervention. Rather, they may be observed, as spontaneous resolution may occur over a period of weeks to months.

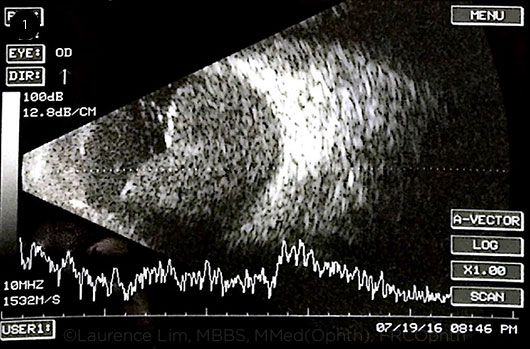

Indications for surgical drainage include retinal apposition (“kissing choroidals,” Fig. 1), uncontrolled IOP, flat anterior chamber, and rhegmatogenous retinal detachment. There is no consensus on the best timing for drainage. In most cases, drainage is performed when B-scan ultrasonography shows signs of clot liquefaction (usually in 7-14 days).

|

|

RETINAL APPOSITION. B-scan showing “kissing choroidals,” a term that describes suprachoroidal hemorrhage with retinal apposition. The scan shows low to medium internal reflectivity, as it was made before the clots liquefied.

|

Surgical Techniques

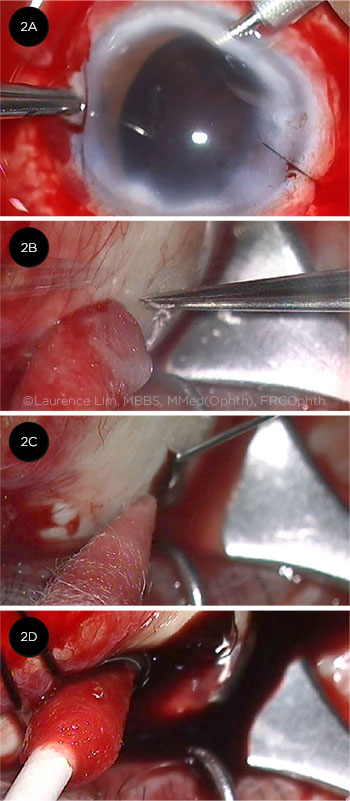

The following techniques may be employed for secondary surgical drainage of SCH (Figs. 2A-2D).

Posterior draining sclerotomy. A 1- to 2-mm posterior draining sclerotomy is made 3 to 4 mm from the limbus in a radial fashion in the quadrant that contains the largest collection of blood (i.e., the highest point of SCH). Care is taken to place it anterior to the vortex veins. Clots that have not fully liquefied can also be evacuated from the sclerotomy with a cyclodialysis spatula.

Increasing or maintaining IOP during drainage. IOP can be maintained by means of a limbal infusion, an anterior chamber maintainer, or a long pars plana infusion if the infusion tip can be visualized in the vitreous cavity (which may be difficult in eyes with apposed SCH). IOP is increased in a controlled fashion to allow for the extrusion of suprachoroidal blood through the sclerotomy.

Pars plana vitrectomy and clot removal. Vitrectomy is not commonly performed for the sole reason of draining the SCH, but it may be used if there is also associated rhegmatogenous retinal detachment or other conditions warranting intraocular surgery. Vitreous incarcerated in the wound can be excised externally.

Injection of heavy liquids. When necessary in selected cases, perfluorocarbon liquid (PFCL) can help to force blood from the suprachoroidal space out through the sclerotomy, allowing more complete removal of the blood. Subsequently, gas or oil may be exchanged for the PFCL to provide an internal tamponade to possibly reduce rebleeding into the suprachoroidal space.

|

|

DRAINAGE SURGERY. (2A) Anterior chamber maintainer is used to avoid hypotony. (2B) Creation of a posterior sclerotomy. (2C) A needle is used to facilitate drainage of blood from the suprachoroidal space. (2D) Gentle pressure with a cotton-tipped applicator can help to express the blood.

|

Conclusion

SCH is a vision-threatening complication, and the guarded prognosis should be discussed with the patient and family. Prompt recognition and appropriate management may limit its consequences and provide a reasonable visual outcome for many patients.

___________________________

1 Davison JA. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1986;12(6):606-622.

2 Eriksson A et al. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1998;24(6):793-800.

3 Desai P et al. Br J Ophthalmol. 1999;8(12):1336-1340.

4 Ling R et al. Br J Ophthalmol. 2004;88(4):478-480.

5 Beatty S et al. Eye (Lond). 1998;12(pt 5):815-820.

6 Speaker MG et al. Ophthalmology. 1991;98(2):202-209; discussion, 210.

7 Givens K, Shields MB. Am J Ophthalmol. 1987;103(5):689-694.

8 Paysse E et al. J Glaucoma. 1996;5(3):170-175.

9 Sharma T et al. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers. 1997;28(8):640-644.

10 Piper JA et al. Ophthalmology. 1993;100(5):699-704.

11 Reibaldi M et al. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015;160(6):1235-1242.

12 Holland EJ et al. Am J Ophthalmol. 1992;114(2):182-187.

13 Ingraham JH et al. Am J Ophthalmol. 1989;108(6):670-675.

___________________________

Dr. Foo is third-year ophthalmology resident, Dr. Tsai is an associate consultant and adjunct assistant professor, and Dr. Lim is a vitreoretinal consultant; all 3 are currently practicing at the Singapore National Eye Centre, Singapore. Financial disclosures: None.