Download PDF

Glaucoma is one of the most common and devastating complications of uveitis, occurring in up to 20% of uveitis patients. Compared with primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG), uveitic glaucoma (UG) occurs in younger individuals, is associated with higher intraocular pressure (IOP), and has variable response to antiglaucoma drugs. The management of UG is difficult because of its confounding etiology, multifactorial pathophysiology, and complex treatment regimen. As a result, accurate diagnosis of underlying etiology of intraocular inflammation is extremely critical to guide therapeutic intervention and achieve favorable outcomes.

Pathophysiology

Uveitis is classified anatomically based on the part of the uvea that is affected, with the anterior type being most frequently associated with UG. The most common etiology of anterior uveitis is idiopathic, accounting for 38% to 70% of cases; however, other causes include autoimmune disorders (e.g., seronegative spondyloarthropathies, Behçet disease, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, sarcoidosis, and juvenile idiopathic arthritis) or infectious disease (e.g., herpes simplex, herpes zoster, syphilis, and tuberculosis). Leakage of lens proteins or retained lens fragments (lens-associated uveitis) as well as trauma may also induce anterior uveitis.

Mechanisms of UG. Uveal inflammation disrupts the blood-aqueous barrier, allowing inflammatory cells to enter the anterior chamber and alter the aqueous outflow equilibrium.

IOP tends to be reduced in early states of ocular inflammation because of decreased aqueous humor secretion from the ciliary body and increased uveoscleral outflow. However, several mechanisms may lead to UG over time: open-angle mechanisms, secondary angle closure, and corticosteroid response.

Open-angle glaucoma. OAG, the most common cause of elevated IOP in uveitis, occurs as a result of mechanical obstruction of the trabecular meshwork by inflammatory cells, fibrin, protein, debris, or precipitates. In addition, direct inflammation of the trabecular meshwork caused by cytokine release from inflammatory cells can further disrupt aqueous outflow. Over time, prolonged inflammation can lead to fibrovascular membrane proliferation and scarring of the outflow pathways.

Closed-angle glaucoma. Inflammation may induce formation of synechiae within the anterior chamber angle or at the pupillary border. In the angle, broad-based peripheral anterior synechiae can cause total closure of the angle. At the pupillary border, circumferential posterior synechiae can block the flow of aqueous fluid from the posterior to anterior chamber, which results in acute angle closure due to iris bombé.

Less commonly, secondary angle closure can also be seen when inflammation and edema of the ciliary body lead to its anterior rotation and subsequent closure of the angle.

Steroid-induced glaucoma. Although corticosteroids are a mainstay in the treatment of uveitis, they can lead to elevated IOP in up to one-third of patients with uveitis. Corticosteroid-induced IOP elevation is due primarily to increased outflow resistance and is thought to result from suppression of phagocytic activity, which leads to increased deposition of glycosaminoglycans and a decrease in prostaglandin synthesis. In steroid-responsive patients, IOP elevation occurs within the first few weeks and can continue for several weeks after the medication has been discontinued.

|

|

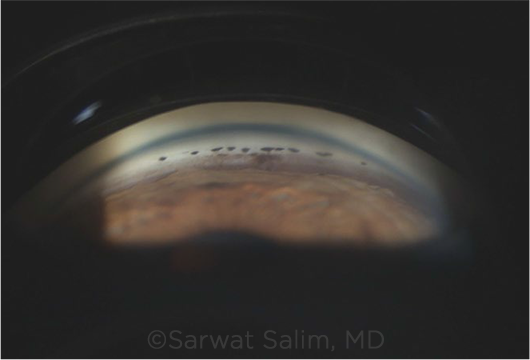

GONIO. Scattered PAS and pigment deposition on gonioscopy in an eye with uveitis.

|

Treatment

The management of UG consists of a multidisciplinary approach involving the patient’s ophthalmologist, rheumatologist, and primary care provider—all with the goal of treating the underlying cause of uveitis, controlling the intraocular inflammation, and decreasing the IOP. The first step is to determine the etiology of the uveitis to choose the appropriate treatment. Intraocular inflammation can be addressed through topical or systemic medications, while elevated IOP is treated with topical and/or surgical methods.

Medical Management

Topical. Depending on the severity of the inflammation and IOP elevation, topical medications may provide adequate control of the disease process.

Anti-inflammatory agents. Corticosteroids are the main anti-inflammatory agents used to treat uveitis, with preference given to stronger topical formulations such as prednisolone acetate or difluprednate. If inflammation is refractory to topical medications or if there is concern about patient noncompliance, periocular corticosteroids can be used as an alternative. The potential adverse effects of steroids include elevated IOP, cataract formation, and local immunosuppression.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are not particularly useful in the treatment of UG, as they may counteract the hypotensive effect of some glaucoma medications, such as brimonidine.

Cycloplegic drugs. Mydriatic agents such as atropine, cyclopentolate, or tropicamide are often added to the regimen to prevent posterior synechiae formation and to relieve discomfort.

Ocular hypotensive medications. For elevated IOP, topical beta-blockers and carbonic anhydrase inhibitors have traditionally been used as the first-line agents for UG. Alpha-2 adrenergic agonists are considered second-line agents and are most useful when employed in combination therapy.

Prostaglandin analogues and cholinergic agents are a relative contraindication because they can exacerbate inflammation through further breakdown of the blood-aqueous barrier.

Rho kinase inhibitors, which act on the trabecular meshwork cells and endothelial cells in Schlemm canal to enhance outflow facility, may be of value.

Systemic medications. Various systemic agents may be tried if the response to topical drugs is inadequate.

Anti-inflammatory agents. Oral corticosteroids may be considered when topical corticosteroids fail to control intraocular inflammation.

Immunomodulatory agents have a significant role in the treatment of noninfectious uveitis, not only in steroid-refractory cases. They also help to improve long-term control of uveitis and to reduce systemic complications of corticosteroids. The conventional steroid-sparing agents include antimetabolites (e.g., methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, and azathioprine) and T-cell inhibitors (e.g., cyclosporine and tacrolimus); however, these medications may fail to control uveitis in up to 40% of cases.

Newer classes of biologics, namely the TNF-α inhibitors (adalimumab, infliximab, certolizumab, and etanercept), have shown significant success in the treatment of refractory disease, with reported remission rates as high as 86%.1 Regular communication with the rheumatologist is essential to monitor systemic side effects of various immunomodulatory agents.

Ocular hypotensive medications. Systemic medications are available for uncontrolled IOP in patients on maximum topical medications or for acute IOP reduction; however, caution must be exercised due to their side effect profile. Oral carbonic anhydrase inhibitors impair renal absorption of bicarbonate, leading to a diuretic response that ultimately lowers IOP. Adverse effects such as hypokalemia, kidney stones, metabolic acidosis, agranulocytosis, and renal/hepatic failure have been noted.

Hyperosmotic agents (e.g., mannitol and glycerol) are used in acute settings with substantial IOP elevation. Notable side effects include hypotension, hyperglycemia, seizures, pulmonary edema, vomiting, and electrolyte imbalances.

Surgery

Surgery is indicated if maximum medical management fails to control IOP. About one-third of UG cases require surgical intervention, with success rates ranging from 65% to 92%.2,3 As a general rule, the success of surgery depends significantly on the suppression of inflammation during the perioperative period. Compared to POAG patients, UG patients have lower rates of overall surgical success and higher rates of postoperative hypotony due to ciliary body dysfunction caused by recurrent intraocular inflammation.

Laser. Nd:YAG laser peripheral iridotomy is indicated for angle closure secondary to iris bombé in the setting of extensive posterior synechiae. Sometimes, multiple and large iridotomies are required, as they may close with active inflammation in the eye.

Cycloablative procedures, either transscleral or intraocular, can exacerbate inflammation, cause hypotony, and lead to phthisis bulbi. Thus, they should be used only as a last resort for refractory UG and treatment must be carefully titrated.

Laser trabeculoplasty is not recommended because of angle alteration. This modality, especially with use of argon-based lasers, has the potential to induce inflammation and damage the trabecular meshwork.

Tube shunts. Glaucoma drainage devices are the preferred first-line surgery in UG, especially in cases with active inflammation. The Ahmed Glaucoma Valve (AGV) is often favored because of its immediate action and its unidirectional valve mechanism, which lowers the risk of postoperative hypotony.

However, if an eye can tolerate high IOP for four to six weeks, a Baerveldt tube should be considered; it has a lower rate of reoperation and may yield lower IOP in the long term. Although no investigations have formally compared AGV to Baerveldt in UG, studies have shown positive outcomes for both. AGV has a one-year success rate of 77% and a two-year success rate of 50%, while the Baerveldt has one- and two-year success rates of 91.7%.4,5

Trabeculectomy. Although filtration surgery is a widely used surgical treatment in UG, it is avoided in eyes with active inflammation, neovascularization, and aphakic lens status. Standard trabeculectomy or the Ex-Press glaucoma filtration device should not be performed without anti-metabolite agents, namely 5-fluorouracil and mitomycin C, which help minimize excessive scarring and decrease failure rates. The long-term success rates for trabeculectomy and Ex-Press with antimetabolites have been found to be as high as 80-90% in patients with well-controlled uveitis, which is comparable to the drainage devices.6

Microinvasive glaucoma surgery (MIGS). The use of MIGS is becoming popular in the treatment of POAG and is under intensive evaluation for UG patients with open angles.

Ab interno trabeculotomy (e.g., Trabectome, gonioscopy-assisted transluminal trabeculotomy, and Trab360), one of the first MIGS procedures to be evaluated in UG, increases trabecular outflow by removing part of the trabecular meshwork. Shimuzi et al. found a 75% success rate with Trabectome; however, the article did not discuss the safety profile and long-term outcomes.7

In a study of canoloplasty in UG, Kalin-Hajdu et al. reported a two-year success rate of 73.7%.8

Scarce data are available on iStent, Hydrus, and Xen in UG, but there is concern that these small-lumen devices might have a high failure rate due to obstruction from inflammatory debris.

___________________________

1 Sharma SM et al. Br J Ophthalmol. Published online March 12, 2019.

2 Ceballos EM et al. J Glaucoma. 2002;11(3):189-196.

3 Ceballos EM et al. Ophthalmology. 2002;109(12):2256–2260.

4 Papadaki TG et al. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;144(1):62-69.

5 Ceballos EM et al. Ophthalmology. 2002;109(12):2256-2260.

6 Muñoz-Negrete FJ et al. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:742792.

7 Shimizu A et al. Clin Ophthalmol. 2014;26(8):2383-2389.

8 Kalin-Hajdu E et al. Can J Ophthalmol. 2014;49(5):414-419.

___________________________

Dr. Jhaj is a glaucoma fellow in the department of ophthalmology at Stanford University in Palo Alto, Calif. Dr. Salim is professor of ophthalmology, Vice Chair of Clinical and Academic Affairs, and director of Glaucoma Service at the New England Eye Center of Tufts University School of Medicine in Boston. Financial disclosures—Dr. Salim: Aerie: C,L.