By Hannah Meyer, BA, Susan M. Culican, MD, PhD, and Philip L. Custer, MD

Edited By: Jane Bailey, MD

Download PDF

EyeNet introduces an occasional series of patient safety cases, written by the American Board of Ophthalmology and appearing in Morning Rounds.

It was turning out to be a long day for Gerard Gooman.* He initially saw his optometrist for a floater and was now sitting in the sub-waiting room of the busy ophthalmology office waiting for a diagnostic test, whatever that meant. As he tried not to rub his eyes, which were still burning from the dilating drops, he listened to the technician calling a patient’s name. If his hearing had been better, he would have realized sooner that she wanted him. He stood up and said, “Oh, that’s me.”

This test was different from any Mr. Gooman had had before. First the IV and then so many photographs of his eyes. When the photos were done, he was told he could leave and that he would be called with the results. As he was being escorted to the front desk, the technician who had given the eyedrops saw him and asked where he had been; his doctor was ready for him. It was then that the other tech who had administered the fluorescein angiogram (FA) realized that a mistake had been made. She had just performed the test on the wrong patient. Mr. Gooman was returned to an exam room and his evaluation completed. He was heard to comment, “That was the most thorough examination I’ve had here.”

|

|

FA. Fluorescein angiogram of a healthy eye.

|

Safety Event Investigation/Root Cause Analysis

An incident report detailing the mis- take was submitted by the office manager through the university’s event reporting system (ERS). Making a submission to the ERS triggers an investigation by a multidisciplinary team from within the practice.1

The practice’s patient safety team was composed of the patient safety officer, the patient safety coordinator, and 2 clinical managers—the lead technician and the front desk manager. The group conducted a thorough investigation, including a root cause analysis (RCA; see “What is root cause analysis?” below). First, the patient safety team identified the factors that contributed to the error.

- The technician who had previously worked with the patient who was correctly scheduled for the FA was reassigned midway through the visit.

- The second tech, who performed the test, had not met the patient and did not verify the identity of the individual called from the waiting area.

- The unaccompanied elderly patient was unaware of what type of diagnostic testing was scheduled for his visit.

- The office protocol required 2-step identification prior to all procedures and completion of a procedure-specific form with check boxes to ensure that critical steps had been performed, including a time-out.2 Unfortunately, there were no forms in the room at the time of this patient’s FA. The tech proceeded without completing the form or performing the time-out.

- No documentation of the event was found in the patient’s medical record, nor could anyone recall having disclosed the event to the patient.

Then the team categorized the factors above as: root causes, contributing factors, or systemic issues.

Root cause. The team determined that the root cause was the failure to comply with standard protocol and procedures. Because the procedure form was not available and not filled out, there was no prompt for the tech to complete the 2-step identification process that the form requires. Further, in the absence of this documentation, there was no procedural time-out. The purpose of the procedure form is to catch wrong patient or wrong procedure events prior to their occurrence.

This failure to comply with procedure is an example of “at-risk behavior” in Just Culture Philosophy.3 (See “What is Just Culture?” below.) To avoid the inefficiency of looking for additional forms to replenish the missing stock, the technician opted to proceed with the testing without completing the necessary paperwork, thereby inadvertently putting the patient at risk. Work-arounds to improve efficiency are considered normal human behavior and should be addressed through coaching. A goal of the ERS and subsequent investigation is to identify systems solutions to mitigate the risk of errors. In the case of at-risk behavior, coaching is intended to educate staff about the potential consequences of noncompliance with safety protocols and to solicit open communication about systems issues that can be implemented to help minimize at-risk behavior in the future (e.g., someone can be assigned the task of checking the stock of forms at the end of each shift).

Contributing factors. Several factors contributed to this error. One of these was poor communication between the technicians working in the office, with changing personnel during the patient’s visit. While “handoffs” are common practice in inpatient settings, they are used much less frequently in an office environment. It would be beneficial to develop protocols for communicating patient information when office staff changes.

To help reduce medical errors, patients must be integrally involved in their own care. As some patients may not feel empowered to question medical processes, practices should make a concerted effort to create an environment that fosters patient engagement. (Note that this effort should extend to family members, who often accompany and advocate for older relatives.) An additional benefit of this communication: It helps identify patients with poor health literacy, a condition that impacts care and compliance.4

Additional systems issues. The lack of disclosure and documentation following the event exposed a gap in clinical staff understanding of how to handle these situations. Education of physicians and staff regarding guidelines for disclosure and documentation began following the investigation. And the error was disclosed to the patient, and documentation of the event was included in the medical record.

Key Concepts

What is root cause analysis? Medical errors that occur at the time the patient interacts with the health care system are termed “active.” “Latent” errors are related to preexisting problems within the system that eventually become manifest, often leading to an adverse event. RCA is a formal technique to investigate errors and adverse events.1 RCA involves interviews with team members, chart review, and creation of a time line and process map that can be used to identify primary (“root”) causes and contributing factors.

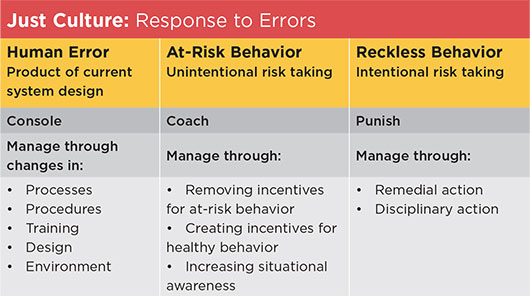

What is Just Culture? Just Culture is an approach to addressing human error in patient care. It recognizes that human error can arise along a continuum from simple forgetfulness and honest mistakes to risk-taking in the form of work-arounds in inefficient systems, and to recklessness. Just Culture seeks to recognize the human factors in behaviorally appropriate ways to implement both robust systems solutions and, when appropriate, behavior modification to reduce medical errors.

___________________________

1 Patient Safety Network: Root Cause Analysis. June 2017. https://psnet.ahrq.gov/primers/primer/10/root-cause-analysis.

Source: Adapted from David Marx, Outcomes Engenuity, https://www.outcome-eng.com/getting-to-know-just-culture/.

|

Patient Safety Principles

Most ophthalmologists are aware of the concerns of incorrect surgical procedures, including wrong intraocular lens (IOL) insertion or operating on the wrong eye. This case highlights the risk of incorrect office procedures. Ophthalmology is an office procedure–intensive specialty. Lasers, intravitreal injections, botulinum toxin injections, cosmetic fillers, and FA are all invasive procedures typically performed in an office setting. Additionally, critical noninvasive diagnostic tests, such as A-scan that is performed to determine IOL power, can have significant safety implications. Each of these encounters creates the potential for wrong patient or wrong procedure mistakes. Up to half of all incorrect IOL insertions are caused by mistakes made in the office.5 These mistakes typically are not detected with the operating room time-out process. In his sentinel article on incorrect eye procedures, Simon reported a case similar to that described here. A patient mistakenly stood up when a name was called and received a laser treatment instead of a visual field.6 Intravitreal injection mistakes have been documented, including wrong patient, wrong eye, wrong drug, and wrong dosage.7

Each office should have protocols in place for 2-step verification of patients prior to office procedures and diagnostic tests, such as full name and date of birth. Procedure forms and checklists help ensure that critical steps are not omitted. Lapses in protocol are frequently responsible for medical errors.8 There are many reasons why members of the care team fail to follow protocols, including being rushed and perceptions that protocols may be unneeded or reduce productivity.9 These biases result in behavior that puts patients at risk and require active management through coaching to help staff understand the rationale and importance of such policies and procedures.

___________________________

*Patient name is fictitious.

___________________________

1 https://psnet.ahrq.gov/primers/primer/13/reporting-patient-safety-events.

2 The Joint Commission. 2018 National Patient Safety Goals Presentation. https://www.jointcommission.org/2018_national_patient_safety_goals_presentation/. Accessed Dec. 22, 2017.

3 Reason J. Human Error. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 1990.

4 Dewalt DA et al. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(12):1228-1239.

5 Steeples LR et al. Eye. 2016;30:1049-1055.

6 Simon JW. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 2007;105:513-529.

7 Kelly SP, Barua A. Eye. 2011;25:710-716.

8 Neily J et al. J Patient Saf. Published online March 16, 2015.

9 Debono DS et al. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:175.

A Risk Management Perspective

The patient in this article mistakenly had an FA as a result of a systems failure, in which the practice’s protocol for patient identification and testing wasnot followed. Also, had the tech asked the patient whether he had provided informed consent, she may have uncovered the mistaken patient identity.

Significant reactions to FA are rare but can be catastrophic. Although this patient was not harmed, the consequences of the identification error could have been quite different. If this patient had been injured after undergoing a test that was not even ordered, the plaintiff’s attorney would have had little trouble convincing a jury of the practice’s negligence.

The practice is to be commended for reviewing its patient identification process after discovering the error. It can also take this opportunity to assess how it conducts FAs and other tests, since patients undergoing them may have comorbidities that can lead to emergencies. The following recommendations may protect patients: 1) Screen for possible contraindications to FA by asking about pregnancy, food/drug allergies, prior reactions to the dye, and a history of asthma. 2) Have an ophthalmologist immediately available. 3) Train staff to recognize reactions to fluorescein. 4) Prepare an emergency kit with basic emergency medical equipment, and check it regularly. Review the FA product insert for guidance on needed medications. Place a label on the outside of the kit listing the drugs, expiration date, dose, etc. 5) Ensure that staff know where to locate the emergency kit. 6) Review the emergency response protocol regularly, and conduct drills.

Cases like this are near misses that provide an important opportunity to review and improve processes that optimize patient safety.

—Written by Anne M. Menke, RN, PhD, OMIC Patient Safety Manager. Reviewed by George A. Williams, MD, chair of the OMIC Board of Directors.

|

Ms. Meyer is the patient safety coordinator, Dr. Culican is an associate professor, and Dr. Custer is a professor; all are in the Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences at Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Mo. Relevant financial disclosures: None.

For full disclosures and the disclosure key, see below.

Full Financial Disclosures

Dr. Culican None.

Dr. Custer Johnson & Johnson: O; Pfizer: O.

Ms. Meyer None.

Disclosure Category

|

Code

|

Description

|

| Consultant/Advisor |

C |

Consultant fee, paid advisory boards, or fees for attending a meeting. |

| Employee |

E |

Employed by a commercial company. |

| Speakers bureau |

L |

Lecture fees or honoraria, travel fees or reimbursements when speaking at the invitation of a commercial company. |

| Equity owner |

O |

Equity ownership/stock options in publicly or privately traded firms, excluding mutual funds. |

| Patents/Royalty |

P |

Patents and/or royalties for intellectual property. |

| Grant support |

S |

Grant support or other financial support to the investigator from all sources, including research support from government agencies (e.g., NIH), foundations, device manufacturers, and/or pharmaceutical companies. |

|