This article is from July 2012 and may contain outdated material.

Normal-tension glaucoma (NTG): Is it a meaningless statistical construct, as Alfred Sommer, MD, MHS, has asserted?1 Should we, as he advised, banish and bury the term? Does NTG simply denote primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) with pressures in the average range? Or is it a separate disease entity?

Leon Herndon, MD, calls NTG a subset of POAG. “The mechanism is the same,” he said. And like POAG, “NTG treatment trials have found lowering pressure significantly halts progression.” Dr. Herndon is associate professor of ophthalmology at Duke University Eye Center in Durham, N.C. He added, “I don’t think it’s a different disease.”

Regardless of the ongoing debate, the challenge for the ophthalmologist is to recognize and treat patients with glaucoma whose untreated intraocular pressure (IOP) is consistently within a statistically normal range. The condition may affect a large number of people: The Beaver Dam and Rotterdam eye studies showed that nearly one-third of glaucoma patients can be classified as having NTG.2,3 The proportion is higher in the Japanese population.4

This month’s update focuses on the diagnosis of NTG; next month’s will address treatment options.

|

|

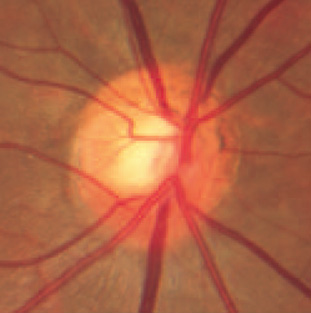

Optic Disc in NTG. Thinning of the superior rim tissue is a common finding in NTG.

|

Dx: NTG

Although the clinical features of the optic disc in NTG are shared with all forms of glaucoma, establishing the diagnosis of NTG remains a challenge. “Because high pressure isn’t a red flag, the diagnosis is more complex than the high-pressure forms of glaucoma,” said Sayoko E. Moroi, MD, PhD. She added that clinicians must appreciate that IOP is a continuous measure affected by both biology and environmental factors, such as medication. Dr. Moroi is associate professor of ophthalmology and visual sciences, glaucoma service chief, and glaucoma fellowship director at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

Rule out masqueraders. Another challenge, Dr. Moroi said, is that other conditions can cause optic nerve pathology that mimics glaucoma without elevated IOP. These include brain mass or tumor, episodes of optic neuritis, trauma to the optic nerve, and hereditary diseases of the optic nerve. Systemic medications, such as ethambutol and isoniazid, can damage the optic nerve and cause optic neuropathy in a patient whose IOP is normal.

However, mimic diagnoses “are quite rare,” said Keith Barton, MD, consultant ophthalmic surgeon of the glaucoma service at Moorfields Eye Hospital in London. “On the advice of our neurologists, we generally don’t refer patients for neurological assessment or neuroimaging unless something in the clinical picture does not fit with the glaucoma diagnosis, for example, a visual field that may be nonglaucomatous in appearance. Part of my practice is dedicated to the management of glaucoma in uveitis. The most common such mimic in this area is the uveitic patient with sarcoidosis, who might also have neurosarcoid instead of glaucoma.”

Dr. Moroi agrees that systemic disorders, including sarcoidosis, tuberculosis, and multiple sclerosis, must be ruled out because they produce optic neuropathies that may mimic glaucoma. Like Dr. Barton, she relies less on tests and more on her clinical judgment. “One thing we have consensus on is that we should define glaucoma by the appearance of the optic nerve.”

Examine the optic nerve. Dr. Moroi assesses the clinical appearance of the neuroretinal rim of the optic nerve for color and contour; the presence or absence of optic nerve hemorrhages; and the degree of excavation of the lamina cribrosa relative to the neuroretinal rim. “If you see pallor of the optic nerve, then you need to evaluate [other] causes for the disease,” she said. “If there’s marked asymmetry in optic nerve appearance, especially if accompanying pallor of the optic nerve, and an afferent pupillary defect, that patient needs an MRI scan to evaluate a potential compressive lesion and to assess for ischemic optic neuropathy.”

Dr. Herndon agrees. The optic nerve should be a nice orange color, he said. A pale rim is a warning sign that it’s something other than NTG. “All you have to do is look at the nerve. If you’re just measuring the pressure, you’ll miss these patients.” He said patients end up in his office because “no one’s looking at the optic nerve.”

According to Dr. Barton, helpful diagnostic signs include optic disc hemorrhages, a clinical appearance of optic disc cupping, areas of retinal nerve fiber layer loss in a typically glaucomatous pattern, and signs of progression in a pattern consistent with glaucoma. However, Dr. Barton cautioned, “When the pressure is normal, diagnosis can be most difficult when the optic disc is anomalous (for example, in myopia), especially if there are field defects related to the myopia.”

Dr. Herndon urges restraint when considering “an OCT or fancy test,” saying, “It’s important to rely on your clinical findings and not always on diagnostic testing.” However, Dr. Moroi said it’s helpful to document the appearance of the nerve with fundus photography. “My preference is to get digital color photos on my patients.” She prefers these fundus photos over laser imaging because she has observed that the newer imaging technologies change faster than the optic nerve does. And if the newer versions of the software are not compatible with older laser imaging files, a patient’s progression cannot be analyzed.

Look for other diagnostic clues. Dr. Herndon also pays attention to visual defect patterns, explaining that glaucoma defects are on a horizontal meridian. “A visual field that respects the vertical meridian could indicate a central nervous system problem.” Other clues include headache, slurred speech, and dizziness. “You don’t want to miss a brain tumor,” Dr. Herndon said. “A pale rim of the optic nerve also may be consistent with a brain mass or tumor.”

Apart from these diagnostic clues, some ophthalmologists have observed a pattern of characteristic features in NTG patients. See “Patient Profiling: NTG vs. POAG.”

Patient Profiling: NTG vs. POAG

NTG patients are similar to typical POAG patients, but they differ in some ways. For example, they tend to present with more central visual field defects than peripheral defects. But, Dr. Herndon said, “not always.”

What else should you look for? Patients with NTG are more likely to have thin corneas, Dr. Herndon added. “They’re also more likely to have some pressure-independent mechanism going on that we don’t know a whole lot about.”

Dr. Moroi agreed. “There’s a concern about their peripheral vascular status and whether that implies something about [the relationship of] their vascular status to the optic nerve.” She added that there’s a stereotypical NTG patient. In general, the patients are female, are thinner, have lower blood pressure, and tend to feel cold.

A recent pilot study that compared the clinical profiles of NTG and POAG patients found that NTG patients are more likely to have lower body mass index and lower systolic blood pressure than their POAG counterparts.1 Patients with NTG also had a lower ratio of prescription to over-the-counter medications. And they were significantly more likely to have a college education than POAG patients (70 percent vs. 42 percent). Lead author Sanjay G. Asrani, MD, associate professor of ophthalmology at Duke University, explained that the study was an attempt to quantify his clinical observations. “We found those people who had POAG were more likely to have other conditions such as obesity, chronic heart disease, high blood pressure. If I have an obese patient with cupping in front me and he has diabetes and normal eye pressures, I would think either in terms of intermittent angle-closure glaucoma or congenital large cupping, but less about NTG.”

Although the profile may not be foolproof, it is another piece of the clinical puzzle. “Normal-tension glaucoma is a diagnosis of exclusion. We have to rule out neurological causes and other things,” said Dr. Asrani. “So it also helps if somebody fits the profile: body mass index lower than normal; detail oriented; highly involved in health care; multiple supplements; optic nerve shows cupping; and there’s a visual field defect. That patient fits the profile of NTG, so I wouldn’t need to be thinking outside the box.”

___________________________

1 Asrani S et al. Curr Eye Res. 2011;36(5):429-435.

|

Take a history. Dr. Moroi asks her patients about:

- Symptoms of sleep apnea

- Signs of subtle hypothyroidism

- Past steroid use, to detect prior steroid-induced ocular hypertension

- Past refractive surgery, to point to an artificially thin cornea that produces a falsely low IOP reading

- Past symptoms of anemia

- Orthostatic symptoms

Measure corneal thickness. The Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study (OHTS) showed central corneal thickness (CCT) to be a powerful predictor of development of glaucoma. Eyes with relatively thin corneas (555 ?m or less) had a threefold higher risk of developing glaucoma than eyes with corneal thickness of greater than 588 ?m.

If the cornea is thin, Dr. Herndon prefers the Pascal Dynamic Contour Tonometer (DCT) over Goldmann tonometry because DCT has been shown to give “measures of true IOP for thin corneas.” For example, a patient of Dr. Herndon’s whose corneal thickness was 480 ?m had an IOP reading of 15 mmHg according to Goldmann tonometry. “The DCT got true pressure of 22 mmHg,” Dr. Herndon said.

Then why not use DCT all the time? It’s not practical, he said. His office has only one machine, plus it’s more time consuming. Besides, he added, all clinical trials are based on Goldmann tonometry.

Obtain multiple IOP readings. Dr. Moroi prefers to withhold treatment until she gets a sense of the IOP range. When an IOP measurement appears suspicious, she always obtains another measurement herself.

“If there’s no visual field loss, fortunately time is on our side,” she continued. “We can try to get additional pressure data points.” Ideally, Dr. Moroi’s NTG suspects will agree to spend a day in the office, for a pressure reading every two hours, so that a modified diurnal pressure curve can be generated. Sometimes there is a wide range in IOP. Alternatively, she has patients at the preperimetric or early stage of glaucoma return in two to six months, at different time points, so that morning and afternoon measurements can be compared. Once treatment begins, she checks to see if the pressure has fluctuated back to the highest untreated IOP reading.

Ultimately, when it comes to diagnosis of NTG, Dr. Moroi relies on her clinical experience. “Glaucoma diagnosis is based on the optic nerve appearance.”

___________________________

1 Sommer A. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129(6):785-787.

2 Klein BE et al. Ophthalmology. 1992;99(10):1499-1504.

3 Dielemans I et al. Ophthalmology. 1994;101(11):1851-1855.

4 Shiose Y et al. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 1991;35(2):133-155.

___________________________

Dr. Asrani reports no related financial interests. Dr. Barton has received lecture honoraria from Allergan and Pfizer; is on the advisory boards of Alcon, Amakem, Glaukos, Kowa, Merck, and Thea; is a consultant for Alcon, Aquesys, Ivantis, and Refocus; has received educational grants or funding from Alcon, AMO, Merck, New World Medical, and Refocus; and owns stock in Aquesys and Ophthalmic Implants (PTE). Dr. Herndonis on the glaucoma advisory board for Alcon. Dr. Moroi receives research funds from Merck.