Download PDF

Antibodies are well known as key components of the immune system that protect against infection. Their ability to specifically recognize particular proteins has been harnessed therapeutically in the form of monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) and intravenous immune globulin (IVIg) to treat numerous ocular and nonocular diseases. However, 2 recent publications indicate that antibodies have a previously unknown function that has major implications for therapeutic use.

Target-independent effects of mAbs. The pioneering studies, led by principal investigator Jayakrishna Ambati, MD, of the University of Kentucky, show that numerous FDA-approved therapeutic antibodies have an important off-target effect: They nonspecifically inhibit blood vessel growth independent of their intended target. Dr. Ambati believes that this newfound function could be utilized as a novel treatment strategy to combat a wide range of diseases involving aberrant angiogenesis.

Through a series of animal and cell culture studies, the researchers found that a subtype of immune globulins, known as IgG1, suppresses angiogenesis by binding to Fc-gamma receptor I (FcγRI) sites on cell membranes.1,2 Their data indicate that the antiangiogenic mechanism of IgG1 antibodies involves the inhibition of proangiogenic macrophage recruitment.

|

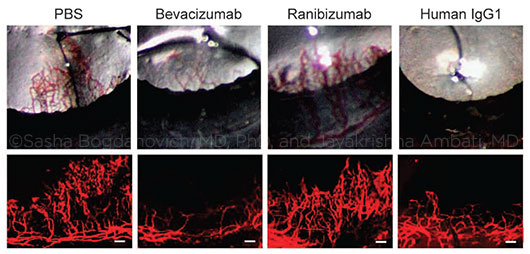

REPRESENTATIVE PHOTOS OF MOUSE EYES (upper row) and corneal flat mounts (lower row) showing reduced growth of blood vessels (CD31+, red) in eyes treated with bevacizumab or human IgG1, but not in eyes treated with ranibizumab. PBS (phosphate-buffered saline) was used for comparison. (Scale bars, 100 μm.)

|

Is IgG1 the key? Many therapeutic mAbs consist of IgG1, which is also the most common class of antibodies in IVIg. To bolster the clinical relevance of their findings, the researchers examined biopsied tissue from organ transplant patients before and after IVIg therapy and found significant reductions in blood vessels after IVIg treatment. This finding suggests that IgG1 antibodies might have a clinically important impact on blood vessel development in humans.

“IVIg may be ripe for rapid repurposing as a systemic angio-inhibitory agent and in the near future as an intraocular inexpensive therapy for multiple neovascular blinding diseases, such as AMD [age-related macular degeneration], proliferative diabetic retinopathy or retinopathy of prematurity,” Dr. Ambati and colleagues wrote.2

Testing ocular therapies. IVIg’s current commercial formulation would require revision before it could be studied in human eyes, Dr. Ambati said. “The pH and osmolarity would have to be adjusted for intraocular use.”

However, clinical testing of the underlying concept is possible with an IgG1-based mAb that ophthalmologists commonly use: the anti-VEGF drug bevacizumab (Avastin). Because bevacizumab is a whole antibody, it has the necessary structural characteristics to bind to FcγRI, whereas ranibizumab (Lucentis), which is an antibody fragment lacking the Fc region, does not, Dr. Ambati explained.

Higher dosage may be needed. “The question is why this second, additional antiangiogenic effect from Fc-receptor binding wasn’t seen in the famous CATT study, which compared Avastin versus Lucentis for age-related macular degeneration,” Dr. Ambati said. “We believe that the reason might be that the dose of Avastin used was insufficient to capture the second effect. Based on our calculations, if you used 8 times the Avastin that we use now intravitreously, you would see this additional mechanism at work and, potentially, have an even better effect on the neovascularization.”

To test this idea, Dr. Ambati and colleagues are planning clinical trials of higher-dose bevacizumab in patients with AMD and with corneal neovascularization. His group’s studies in mice indicated that the current intravitreal dose of bevacizumab given to AMD patients, 1.25 mg (volume: 50 μL), would have to be increased to 10 mg to see an antiangiogenic effect from FcγRI binding, Dr. Ambati said.

Systemic considerations. The discovery that an entire subclass of antibodies suppresses both angiogenesis and macrophage infiltration, which is involved in metastasis of some tumors,3 is also relevant to cancer treatment, Dr. Ambati said. For instance, it might explain why oncologists have reported antimetastatic effects from treating patients with immune globulin,4,5 he said. It also suggests the need for caution in prescribing mAbs or high-dose IVIg for patients with preexisting blood vessel disease, he said.

—Linda Roach

___________________________

1 Bogdanovich S et al. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy. Published online Jan. 28, 2016. www.nature.com/articles/sigtrans20151.

2 Yasuma R et al. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy. Published online Jan. 28, 2016. www.nature.com/articles/sigtrans20152.

3 Leek RD et al. Cancer Res. 1996;56(20):4625-4629.

4 Merimsky O et al. Int J Oncol. 2002;20(4):839-843.

5 Shoenfeld Y et al. Isr Med Assoc J. 2001;3(9):698-699.

___________________________

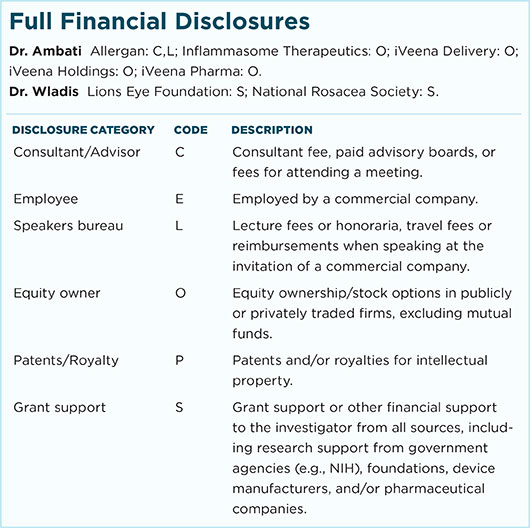

Relevant financial disclosures: Dr. Ambati is named as an inventor on patent applications filed by the University of Kentucky relating to the technology used in this work.

For full disclosures and disclosure key, see below.

More from this month’s News in Review