This article is from August 2012 and may contain outdated material.

The decision to use an approved drug for a new indication gets to the heart of the practice of medicine. It’s legal, and doctors do it every day, exercising their clinical judgment and acumen. For ophthalmologists, the rapid expansion of anti-VEGF drugs across a multitude of conditions is a case in point—and it raises important questions about when to use a drug and when to think twice.

The decision to use an approved drug for a new indication gets to the heart of the practice of medicine. It’s legal, and doctors do it every day, exercising their clinical judgment and acumen. For ophthalmologists, the rapid expansion of anti-VEGF drugs across a multitude of conditions is a case in point—and it raises important questions about when to use a drug and when to think twice.

Recently, Adrienne W. Scott, MD, assistant professor of ophthalmology at Wilmer Eye Institute, used intravitreal Avastin (bevacizumab) preoperatively in a patient with retinal detachment secondary to proliferative sickle cell retinopathy. In doing so, she was traveling a course begun in 2005, when the drug was first used off label in the eye to treat neovascular age-related macular degeneration (AMD).

That year, while waiting for FDA approval of the anti-VEGF agent Lucentis (ranibizumab), which was in development for the treatment of wet AMD, Philip J. Rosenfeld, MD, PhD, made an intuitive clinical decision and injected the ophthalmic drug’s systemic counterpart into the eyes of patients with advanced disease. Within months, the use of intravitreal Avastin to treat wet AMD had become a global phenomenon.

Almost as quickly, doctors began using Avastin for a host of other retinal diseases with similar underlying pathophysiology. By 2006, reports had surfaced on its use to treat proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR), macular edema in retinal vein occlusion (RVO), iris neovascularization, choroidal neovascularization (CNV) caused by pathological myopia, and CNV in angioid streaks. And by 2008, Avastin had been used to treat at least 51 different ocular conditions.1

The list keeps growing. Anti-VEGF drugs have now been used in novel fashion to treat subretinal neovascularization in idiopathic juxtafoveal retinal telangiectasis, histoplasmosis CNV, nonclearing vitreous hemorrhage, diabetic macular edema (DME), and retinopathy of prematurity (see “ROP: A Cautionary Tale”). Beyond retinal disorders, the list includes neovascular glaucoma and anterior segment neovascularization; for the latter use, the drug may be applied topically or subconjunctivally.2 (The present article will focus on intravitreal therapy.)

So by the time Dr. Scott used Avastin to treat sickle cell retinopathy, the literature was replete with evidence to support her decision. Specifically, Avastin already had become an accepted treatment for PDR, which has similarities to sickle cell retinopathy, she explained. “We worry [with sickle cell] about our ability to manage surgical

bleeding due to excessive neovascularization. The fibrovascular complexes in proliferative sickle cell retinopathy also have to be carefully dissected, so the disease process is similar,” she said.

Making such treatment decisions calls for understanding biological plausibility, making links between one condition and another, and even giving special consideration to something as routine as informed consent. And in the case of compounded medications, it also means scrutinizing the source.

ROP: A Cautionary Tale

Helen A. Mintz-Hittner, MD, started using bevacizumab to treat retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) after a vitreoretinal specialist at a hospital, who had been treating AMD patients with the drug, administered it to a few infants with stage 3+ ROP and thought that it worked in that setting. The hospital’s institutional review board (IRB) wanted a randomized study before allowing the drug’s use on a routine basis, and Dr. Mintz-Hittner organized the study.1

Before bevacizumab, ROP treatment options consisted of external cryotherapy or lasering all of the avascular retina, which in very small zone I cases might ablate three-fourths of the retina, said Dr. Mintz-Hittner, a pediatric ophthalmologist who is a professor of ophthalmology and visual science at the University of Texas Medical School at Houston. “The outcomes can be just awful with laser, but they are so much better now with bevacizumab.”

Not everyone agrees. Perhaps no other use of anti-VEGF therapy has generated as much controversy as bevacizumab for ROP.

The reason? “These babies are relying on VEGF for normal vascularization,” Dr. Scott said. “We have a good treatment for ROP, the gold standard, which is laser. We know that’s safe. I would definitely use bevacizumab very hesitantly. The jury is still out as far as utility and when and where to use it.”

Dr. Drenser, who was a cofounder of the BLOCK-ROP study, which tested laser versus Avastin for ROP, agreed. She describes herself as on the fence regarding anti-VEGF for ROP. “I am not one of those adamantly opposed. I still maintain that it’s a valid treatment in the right circumstances,” she said. “That being said, I will hedge that statement.”

Among her concerns are findings from other studies, including the ETROP (Early Treatment of ROP) and APROP (Aggressive Posterior ROP) trials, which dispute Dr. Mintz-Hittner’s report that outcomes were better with bevacizumab than with laser. Dr. Drenser also cited a study that found a reduction of circulating VEGF in neonates one and two weeks postinjection.2 “This has a lot of implications in gut formation, lung formation, and brain formation,” she said, explaining that neonates, unlike adults, depend on VEGF for organogenesis.

On the other hand, Dr. Drenser said that anti-VEGF is “a nice choice” if you can’t administer appropriate laser treatment because of hemorrhage in the eye or media opacity.

What’s the dose? Dr. Drenser uses one-quarter to one-third of the adult dose of Avastin, but she said that dosing needs to be studied.

Dr. Mintz-Hittner acknowledged the concerns. “As far as the general use of [bevacizumab for ROP], it’s very controversial.” But, she added, “We still feel that it’s extremely good, especially for severe zone I, stage 3+ cases. In such cases, bevacizumab is really probably the treatment of choice.” These are patients in whom laser won’t do well because of a retina that is very small or that can’t be seen as a result of hemorrhage or an inability to dilate the pupils adequately.

Timing and follow-up are critical. “If you use [bevacizumab] at the wrong stages (stages 1, 2, 4, or 5) or can’t get good follow-up, then you can have problems,” Dr. Mintz-Hittner said. “I use it only for stage 3+. And if you’re worried that you’re going to lose the patient to follow-up, then laser therapy of the peripheral retina—after the zone I retina has enlarged substantially—is appropriate.”

Dr. Drenser agreed with the concern about loss to follow-up, adding that these babies need to be followed weekly for up to 72 weeks.

OMIC has not adopted a formal position on Avastin for ROP, but it encourages the following:

- Obtain IRB approval from your institution and investigational new drug (IND) approval from the FDA, especially for use of the medication on more than one patient.

- Contact investigators in existing clinical trials to learn about dosing, indications, and informed consent. Consult the listing of ROP trials at www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?term=ROP.

___________________________

1 Mintz-Hittner HA et al. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(7):603-615.

2 Sato T et al. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;153(2):327-333.e1.

|

Anti-VEGF Drugs on the Market

Although pegaptanib sodium (Macugen) was the first anti-VEGF agent approved for use in the eye, it blocks only one of the biologically active isoforms of VEGF-A; it has largely been superseded by the following drugs, which block all of the active isoforms.

Bevacizumab (Avastin). There are no approved ocular indications for bevacizumab. But, because of cost, said Stefanie G. Schuman, MD, “The majority of the time we start with Avastin.” Dr. Schuman is assistant professor of ophthalmology at Duke Eye Center in Durham, N.C.

Dr. Scott agreed. “It probably is the most commonly used medication all around among retina specialists for retinal vascular diseases because of the efficacy combined with the convenient price.” She added that the cost—less than $150 per treatment—makes it easier for patients to get insurance clearance than for ranibizumab, especially in conditions other than wet AMD.

Ranibizumab (Lucentis). First approved for subretinal CNV in AMD, the label was expanded in June 2010 to include macular edema following RVO. Approval for DME is expected soon. The cost is about $2,000 per treatment.

Aflibercept (Eylea). Formerly known as VEGF Trap-Eye, Eylea was approved in November 2011 for subretinal CNV secondary to AMD. Reimbursement codes for Eylea are changing, and various payers may have different coverage policies.

The cost is $1,850 per injection. “Most patients on Avastin don’t want to pay the additional copay that might be required,” Dr. Schuman said. “But for patients we are treating who don’t have a complete response to Avastin, we are prepared to try Eylea.”

|

|

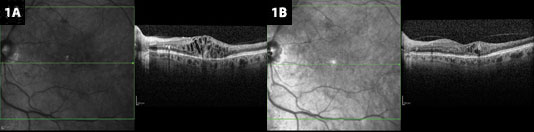

Anti-VEGF for BRVO. (1A) Edema resulting from branch retinal vein occlusion, before treatment. (1B) After treatment with bevacizumab, heme is clearing, and cystic changes have decreased.

|

Common Denominator in Anti-VEGF Tx

Dr. Scott’s decision to try Avastin for a new condition makes biological sense. According to Kimberly A. Drenser, MD, PhD, “The drug works very specifically on VEGF. Its only action is a pan-blockade of VEGF.” Unlike steroids, which work on multiple pathways but have a higher side-effect profile, anti-VEGF drugs are very specific and targeted. “So it’s easy to rationalize for a multitude of diseases for which there’s either a proven or theoretical rationale for using an anti-VEGF drug.” Dr. Drenser is a physician at Associated Retinal Consultants and director of ophthalmic research at William Beaumont Hospital (both in Royal Oak, Mich.) and assistant professor of biomedical sciences at the Eye Research Institute at Oakland University, Rochester, Mich.

Nancy S. Holekamp, MD, director of the retina service at Pepose Vision Institute and clinical professor of ophthalmology at Washington University in St. Louis, agreed. Anti-VEGF drugs are dual-purpose agents, stopping both leakage from existing vessels and growth of new blood vessels, she said. “A lot of retinal disease boils down to those two pathophysiologies.”

There’s another important reason that anti-VEGF is being used for so many conditions, said Dr. Drenser. The injections tend to be well tolerated in adults. “So there’s also a considerable chance for benefit and not a big risk for complications. I think that led to its expansion of use.”

Anti-VEGF Concerns

VEGF has both pathogenic and protective effects. But the “it can’t hurt” theory can be carried too far—anti-VEGF drugs should not be used to treat diseases where VEGF suppression isn’t the target. “Treatment requires biological plausibility,” Dr. Holekamp said. So from a pathophysiologic perspective, it doesn’t make sense to use anti-VEGF drugs to treat certain conditions, such as central serous retinopathy and polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy.

Yet perhaps out of desperation—and with the knowledge that intravitreal injections are generally well tolerated—some doctors treat those conditions with anti-VEGF agents anyway, Dr. Drenser said. But she warned that the very mechanism that makes anti-VEGF treatment effective for so many conditions can also backfire. Why? At high levels, VEGF results in abnormal vascularization, but at low levels, it’s neuroprotective.

When not to treat. “If I don’t see vascular angiographic leakage or macular edema—one or both of the signs that indicate elevated VEGF—then I don’t treat with an anti-VEGF agent,” she said.

To determine VEGF levels, Dr. Drenser relies on both optical coherence tomography (OCT) and fluorescein angiography for evidence of vascular leakage. “That tells me that the level of VEGF is rising,” she said. But, in the absence of choroidal neovascularization, there is a risk of exacerbating geographic atrophy. “My concern is that if I don’t see any evidence of leakage, I’m going to increase the loss of neurons by blocking VEGF’s neuroprotective effect.”

To avoid exacerbating neuron loss, Dr. Drenser uses anti-VEGF drugs cautiously in the presence of dry AMD or any ischemic disease that doesn’t have obvious secondary pathology, such as vascular permeability.

Possible stroke or bleeding. Dr. Scott is reluctant to use bevacizumab in patients with recent stroke or gastrointestinal bleeding because of a possible link between bevacizumab and the recurrence of strokes or GI bleeds. She emphasizes, however, that this has not been conclusively demonstrated in clinical trials. Thus, in patients with multiple systemic risk factors, she’s more likely to opt for something other than anti-VEGF therapy.

Unanswered questions. The long-term effects of blocking VEGF raise questions, said Dr. Schuman. Will a continual VEGF blockade cause retinal atrophy? Will it prevent normal vascular formation? At Duke, she said, doctors use spectral-domain OCT and autofluorescence imaging to look for any atrophic areas or retinal thinning. If they find it, they may extend the interval between treatments.

Compounding

In the summer of 2011, four separate clusters of infectious endophthalmitis associated with injection of bevacizumab were identified in Veterans Affairs hospitals and/or the community in Los Angeles, Miami, Minneapolis, and Nashville.

The outbreaks were attributed to the compounding of bevacizumab, which, because it is formulated for systemic intravenous administration to cancer patients, must be specially prepared and divided into individual doses for intravitreal injection. Such preparation requires aseptic technique and facilities to maintain the sterility of the medication vial and the syringes.

The endophthalmitis outbreaks, which resulted in blindness in some cases, caused the FDA to issue a warning to physicians to ensure that drug products are obtained from appropriate, reliable sources. The FDA also encouraged doctors to report any adverse events, side effects, or product quality problems related to use of compounded bevacizumab. See www.fda.gov/Drugs/Drugsafety/ucm270296.htm.

In response to these outbreaks, the Academy issued a Clinical Statement1 containing a number of recommendations, including:

- Select an accredited compounding pharmacy. For a list, consult www.pcab.org/accredited-pharmacies.

- Ask the pharmacy how it compounds Avastin (it should state that it complies with USP 797).

- Record the lot number of the medicine vial and the lot number of the syringe in the patient’s chart for future tracking.

A “Perspective” article examining the issues urged caution but blamed the problem on human error and compounding procedures, not bevacizumab.2 The authors urged strict adherence to USP standards. “This is why USP Chapter 797 always should be followed when fractionating a vial of bevacizumab.”

___________________________

1 American Academy of Ophthalmology. Clinical Statement: Verifying the source of compounded bevacizumab for intravitreal injection. Feb. 2012.

2 Gonzalez S et al. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;153(2):196-203.

|

Promising Clinical Applications

Retinal disorders. Dr. Scott sees patients at both a major academic center and a satellite clinic; at the latter, bevacizumab is the only anti-VEGF in stock. “I use quite a bit of bevacizumab. I do think it’s an effective anti-VEGF therapy, even though it’s not FDA approved at this time,” she said.

“We’ve shown efficacy of intravitreal bevacizumab for DME with monthly injections, as well as for CNV from other causes.” Among her successes: multifocal choroiditis,

panuveitis, and other types of CNV related to uveitic diseases. “Bevacizumab has also been a mainstay in treatment for vein occlusion patients,” Dr. Scott said. “It works very well there.” And in myopic CNV, she said, “You can get remission of the CNV process after a limited number of injections.”

Presurgical use. Before surgery for tractional retinal detachment related to PDR, Dr. Scott uses bevacizumab to facilitate the dissection of neovascular membranes, reduce the likelihood of intraoperative bleeding, and thus decrease the length of surgery. There is some concern that bevacizumab can cause such rapid contraction of neovascular membranes in eyes with extensive PDR that it can lead to or exacerbate retinal detachment. “For this reason,” Dr. Scott said, “it is critical to bring the patient to the operating room within a week of the bevacizumab injection.”

Prevention of neovascular glaucoma. According to Dr. Schuman, anti-VEGF therapy is useful in preventing neovascular glaucoma in patients with CRVO. “When we see any signs of neovascularization, we can use anti-VEGF injections to stop growth of new blood vessels and prevent neovascular glaucoma.”

Pediatric use. Dr. Drenser, who has a particular interest in pediatric retinal disorders, has used bevacizumab in children to treat Coats disease and familial exudative vitreoretinopathy.

Update Your Consent Forms

OMIC provides informed consent forms for all anti-VEGF injections, including both on- and off-label uses. Now there’s one for Eylea, too.

For all the forms, go to www.omic.com.

|

Dosing Considerations

When administering anti-VEGF injections for off-label uses, most doctors use the same dose as for AMD, the experts said. “Very, very rarely will I alter that,” said Dr. Scott, who typically uses the 1.25-mg dose of Avastin. She added that although there are advocates for 2.5 mg, and the science behind this makes sense, the clinical evidence doesn’t support the higher dose.

Dr. Schuman usually starts with the standard AMD dose and considers increasing it if the patient does not respond. Occasionally, she and her colleagues may double the dose.

Dr. Holekamp recently doubled the dose to treat macular edema from radiation retinopathy, which is VEGF mediated. Although the regular dose eliminated the edema at two weeks, the leakage returned at four weeks. “I doubled the dose and it lasted longer,” she said, stressing that there was biological plausibility for her decision.

Packaging caveat. Avastin and Lucentis come packaged in different doses. The dose of Avastin in a prefilled syringe is 1.25 mg per 0.05 mL. Most doctors inject the entire 0.05 mL, Dr. Holekamp said.

However, although the approved dosage of Lucentis is 0.5 mg per 0.05 mL, it is dispensed in a vial containing 0.2 mL, giving physicians the option of doubling the dose by doubling the volume. But Dr. Holekamp cautioned that injecting an increased volume can lead to a spike in intraocular pressure. If you use twice the volume, be sure to measure the IOP, she said.

Dr. Holekamp added, “A vial [of Lucentis] is to be used only for a single patient,” as stated in the prescribing information. Some retina specialists in the United States have gotten into trouble for violating that rule, she said.

Eylea dosing. Eylea is new to the anti-VEGF market, so experience with its on-label use is limited but growing, Dr. Holekamp said. According to the prescribing information, the recommended dosage is 2 mg every four weeks for the first 12 weeks, followed by 2 mg once every eight weeks. It may be injected as frequently as 2 mg every four weeks, but additional efficacy was not demonstrated with the more frequent dosing regimen.

Follow-up. As with anti-VEGF use for AMD, patients being treated for other conditions are typically followed every four to six weeks for repeat injections as needed, Dr. Schuman said. However, a few conditions, including idiopathic CNV, myopic CNV, and presumed ocular histoplasmosis syndrome, generally respond to just a few injections; in these diseases, there’s probably not a continuous upregulation of VEGF. In diabetes, on the other hand, upregulation frequently continues—and so does the treatment regimen for some patients.

Dr. Schuman warned that optimal frequency and duration of dosing for off-label uses remains unknown. “Treatment by an experienced clinician is necessary to determine the patient’s response and need for additional injections,” she said.

The Art and Practice of Medicine

For Dr. Holekamp, the application of anti-VEGF drugs to so many conditions shines a light on what doctors do and how they make decisions. “Based on our training and experience, if we think anti-VEGF therapy has biological plausibility and we give patients proper informed consent, we are engaging in the practice of medicine. It’s what we do. It’s why I’ll never be replaced by a computer.”

___________________________

1 Gunther JB, Altaweel MM. Surv Ophthalmol. 2009;54(3):372-400.

2 Hamid H et al. Cornea. 2012;31(3):322-334.

Meet the Experts

KIMBERLY A. DRENSER, MD, PHD Physician at Associated Retinal Consultants and director of ophthalmic research, William Beaumont Hospital (both in Royal Oak, Mich.), and assistant professor of biomedical sciences at the Eye Research Institute, Rochester, Mich. Disclosure: Is a consultant for Synergetics and has equity in FocusROP and Retinal Solutions.

NANCY S. HOLEKAMP, MD Director of the retina service, Pepose Vision Institute, and clinical professor of ophthalmology, Washington University, St. Louis. Disclosure: Is a consultant for Allergan and Genentech and is on the speakers bureau for Genentech, Regeneron, and Sequenom.

HELEN A. MINTZ-HITTNER, MD Professor of ophthalmology and visual science, University of Texas Medical School at Houston. Disclosure: None.

STEFANIE G. SCHUMAN, MD Assistant professor of ophthalmology, Duke Eye Center, Durham, N.C. Disclosure: None.

ADRIENNE W. SCOTT, MD Assistant professor of ophthalmology, Wilmer Eye Institute, Baltimore. Disclosure: None.

|