By Joseph N. Giacometti, MD, and Robert L. Lesser, MD

Edited by Thomas A. Oetting, MD

This article is from September 2011 and may contain outdated material.

On a sunny spring day, Jack Wilson* visited his optometrist for a routine contact lens fitting. A month earlier, the 12-year-old’s BCVA was 20/20 in both eyes. But at this follow-up appointment, even though Jack hadn’t noticed any recent changes in his vision, the optometrist found that Jack’s BCVA in his right eye was now 20/40. A dilated exam revealed disc edema in Jack’s right eye and a normal disc in his left eye. Concerned, the optometrist referred Jack to us for an urgent neuro-ophthalmic consultation.

We Get a Look

At our initial evaluation, Jack appeared to be a normal, healthy boy. He denied any history of eye pain (with or without eye movement), eye redness or discharge, headaches, diplopia or subjective changes in color vision; and he confirmed that he had not noticed any decreased vision in his right eye. His medical history included recent anti-biotic treatment for a skin rash.

Jack’s BCVA was 20/40 in his right eye and 20/20 in his left. His color vision was full bilaterally. Testing with the Amsler grid revealed generalized distortion in the right eye. Ocular motility was normal. His pupils measured 3.5 mm bilaterally, reacting 2+ on the right and 3+ on the left, with an afferent pupillary defect in the right eye that was neutralized by a 0.6 neutral density filter.

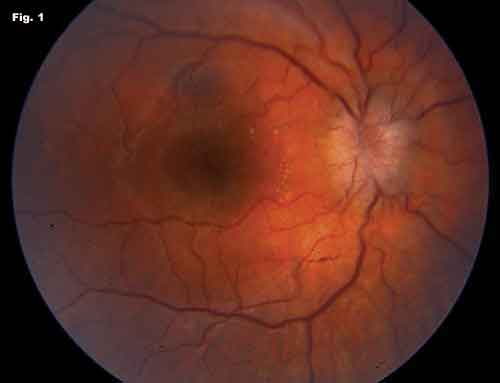

His external examination was normal, with no ptosis, lid retraction, exophthalmos or palpable preauricular nodes. Cranial nerve testing, anterior segment evaluation and his IOP were all normal. His dilated funduscopic exam showed diffuse 360-degree edema of the right optic disc with profound elevation and blurring of disc margins. There were no disc hemorrhages. Exudates were present along the nasal edge of the macula in the affected eye (Fig. 1). The left fundus was normal.

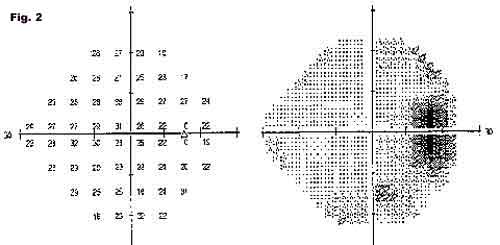

Humphrey visual field testing showed an enlarged blind spot in the right eye (Fig. 2); the left eye was within normal limits. An MRI of the brain and orbits performed prior to his visit was normal.

Critical Clues

In a young, previously healthy patient with unilateral decreased vision, disc edema and macular exudates, infectious neuroretinitis is the most likely diagnosis. When no macular exudates are present, the differential diagnosis includes optic neuritis or an infiltrative disease of the optic nerve.

Our patient was generally healthy and had no history of chronic disease, recent systemic illness or recent travel. However, the family had two kittens at home. Jack stated that neither kitten had ever scratched or bitten him—but they had recently been treated for fleas. Upon further questioning, we discovered that the skin rash Jack had been treated for was presumed to have resulted from fleabites on both arms; this had occurred about two or three months prior to our evaluation.

With this information, we established a working diagnosis of neuroretinitis secondary to cat-scratch disease (also known as cat-scratch fever). With lab results pending, we initially opted to observe without treatment, as cat-scratch fever tends to be a self-limited disease.

Lab Results and Treatment

Bartonella henselae IgG titer was positive and Lyme testing was negative, confirming the diagnosis of cat-scratch disease.

At Jack’s two-week follow-up visit, he reported having a “dark” sensation in his right eye, but this had become evident to him only after the diagnosis was made. At this point, the BCVA in his right eye had improved to 20/25-2, and the disc edema and macular exudates were markedly reduced.

A pediatric infectious disease specialist saw Jack the next day. Even though Jack was improving, the specialist elected to treat him with a four-week course of oral doxycycline (100 mg twice a day). Two months later, after Jack completed the treatment course, his vision was 20/20-2; the disc edema and macular exudates resolved over the following months.

|

|

|

The Patient’s Right Eye. (Fig. 1) Fundus photograph of the patient’s affected eye shows diffuse 360-degree disc edema with blurring of the disc margins. Exudates are present along the nasal portion of the macula. (Fig. 2) Automated visual field testing of the same eye reveals an enlarged blind spot.

|

Discussion

B. henselae, the bacterium primarily responsible for cat-scratch disease, is among the organisms most commonly associated with infectious neuroretinitis. About 1 or 2 percent of patients infected with B. henselaedevelop neuroretinitis.1 Other ocular sequelae of B. henselae include focal retinitis or choroiditis, abnormal retinal vasoproliferation and retinal arteriolar occlusions. 2

The domestic cat is the organism’s primary host, and the cat flea is considered the most important transmitting vector among these animals. More than 90 percent of cases of cat-scratch disease are associated with a history of contact with kittens and cats that are less than a year old.3

Other possible causes of infectious neuroretinitis include syphilis (see the July/August Morning Rounds, “The Patient With Masquerading Blindness”), toxoplasmosis, toxocariasis, Lyme disease and tuberculosis. There have been some reports of neuroretinitis occurring after a viral infection, specifically with herpes simplex virus, hepatitis B or mumps.4

The typical initial presentation of B. henselae–associated neuroretinitis is painless, unilateral visual loss of varying degrees, associated with ipsilateral optic disc edema in young patients. Central or paracentral visual field defects and an afferent pupillary defect are common findings. Systemic symptoms—notably lymphadenopathy, fever and malaise—occasionally precede or accompany the ocular manifestations. Macular exudates tend to develop later in the disease course.3

The history should focus on exposure to household pets and any recent skin trauma or rashes. The diagnostic workup should include laboratory testing for B. henselae antibodies, including direct immunofluorescent assay as well as ELISA testing. These patients, unlike those with optic neuritis, can be reassured that they have no risk of developing multiple sclerosis. MRI studies usually are not needed.

B. henselae–associated neuroretinitis generally is a self-limited disease. Immunocompetent patients usually have resolution of disc edema and macular exudates over one or two months without treatment. Immunocompromised patients, however, do benefit from treatment. Some clinicians advocate use of antibiotics—two to four weeks of doxycycline or erythromycin, with or without rifampin—in immunocompetent patients with severe infection. When treating a child, as in our case, ophthalmologists should consult with a pediatric infectious disease specialist.

In conclusion, when you evaluate a case of unilateral disc edema, the presence of macular exudates (although they are not always present initially) raises the likelihood of infectious neuroretinitis. Typical clinical history along with positive laboratory testing confirms B. henselae as the etiology. Although these patients usually improve clinically without treatment, some physicians favor the use of antibiotic therapy.

___________________________

1 Kalogeropoulos, C. et al. Clin Ophthalmol 2011;5:817–829.

2 Curi, A. L. et al. Int Ophthalmol 2010;30(5):553–558.

3 Roe, R. H. et al. Int Ophth Clin 2008;48(3):93–105.

4 Smith, C. H. in Walsh and Hoyt’s Clinical Neuro-Ophthalmology, Vol. 1, 6th ed. (Philadelphia, Lippincott, 2005),333–336.

___________________________

* Patient name is fictitious.

___________________________

Dr. Giacometti is a resident in ophthalmology and Dr. Lesser is clinical professor of ophthalmology and visual science and of neurology; both are at Yale University.