By Annie Stuart, Contributing Writer, interviewing Evan H. Black, MD, FACS, James D. Douketis, MD, and Tamara R. Fountain, MD

Download PDF

Operating as they do in a highly vascularized anatomic area, oculoplastic surgeons often juggle the risks of systemic thrombotic events and vision-threatening hemorrhage. As a result, the decision of whether to stop or continue antithrombotic medications has long been a source of concern for surgeons and their patients.

And thanks to demographic trends and several recently approved antithrombotics, oculoplastic surgeons are reconsidering this issue.

Increasing usage. The use of antithrombotics is on the rise in the United States because of the increasing prevalence of atrial fibrillation and other cardiovascular diseases among the aging population.1 Even aspirin use has become almost ubiquitous, especially in middle-aged and older patients, many of whom are being treated prophylactically for heart disease, said Evan H. Black, MD, FACS, who practices in the Detroit area.

Advent of NOACs. The medications known as novel anticoagulants (NOACs), which are prescribed for the prevention and treatment of thrombosis, are becoming more widely used as an alternative to warfarin and other antithrombotics. Given the relatively recent approval of these drugs in the United States, cardiologists are still sifting through the pros and cons of NOACs (see “Navigating NOACs”). Ophthalmologists have even less to go by, as no randomized clinical trials have been conducted on NOACs and eye surgeries, although case series are available.

|

|

BLEED. Six days after upper eyelid ptosis repair. The patient had continued to take 81 mg of aspirin daily.

|

Keys to Success

In this shifting environment, the experts offer some general guidance.

Treat the individual. There is no one-size-fits-all approach to ophthalmic surgery and perioperative use of antithrombotics, said hematologist James D. Douketis, MD, at McMaster University in Canada. “What’s needed is a tailored approach, depending upon the type of drug the patient is taking, type of surgery, and type of anesthetic—as well as the renal function of the patient.”

Consult and communicate. Full communication with the patient and the prescribing physician is key to ensuring the best possible outcome, said Tamara R. Fountain, MD, at Rush University in Chicago. “As the operating surgeon, you should not be the one to tell the patient whether or not to withdraw medication and for how long. Whether internist, cardiologist, or neurologist, the prescribing physician knows the risk profile much better than you and is the appropriate person to make this call.”

Dr. Black agreed. “These medications can be critical for preventing mortality and morbidity. If a patient has a medical indication, don’t go it alone. This potentially puts the patient at medical risk and increases your medicolegal liability.” For instance, in patients with atrial fibrillation or mechanical heart valves, 20% of thromboembolic episodes are fatal, and 40% cause permanent disability.1 Thrombosis from premature discontinuation of antiplatelet therapy in patients with stents is fatal in up to 40% of cases.1

Questions to Ask the Patient

A thorough history is essential, as up to 40% of patients undergoing oculoplastic procedures are on antithrombotics—and many of them may not accurately report their medication use.2

Which antithrombotics are you on? “In my practice, I’ve seen bleeding after everything from fish oil to aspirin to Coumadin,” said Dr. Fountain. “Ask about blood-thinning medications, but don’t just leave it at that. Give examples. And be sure to ask about aspirin, which is often self-prescribed and doesn’t show up on a patient’s preprinted Walgreens list.”

Why are you taking this medication? Is it a prophylactic measure to prevent a heart attack or an embolism? Or has the patient had atrial fibrillation or a previous embolic event such as pulmonary embolism or deep vein thrombosis (DVT)? “This information may help you gauge the level of risk,” said Dr. Douketis.

How is your kidney function? Drugs depend upon the kidney for clearance to one degree or another, Dr. Douketis noted. “However, some drugs, such as the NOAC dabigatran [Pradaxa] are largely excreted by the kidneys, so a patient with kidney problems would need more time to clear the drug before surgery.”

Make sure the patient’s renal function is checked 7 days prior to surgery. Creatinine clearance can help determine when agents should be discontinued.3

A note on self-medication. Communication with the patient’s cardiologist or primary care physician isn’t necessary if a patient is taking an aspirin a day for prevention and has not been told to do so by a doctor, said Dr. Black. “In these cases, we simply tell the patient to discontinue aspirin a week before surgery,” he said.

Blood-thinning supplements and vitamins (such as fish oil and vitamin E) pose a particular challenge, as their anticoagulant effects can vary. “I wouldn’t cancel a surgery if a patient had continued taking supplements. However, as extra insurance, our instructions do ask patients to stop these for about a week before surgery,” Dr. Black said. For his part, Dr. Douketis said that these remedies “don’t have much of an effect and can be continued during surgery.”

Questions to Ask Yourself

Managing patients on antithrombotics involves a risk-benefit analysis.

How important is the surgery? If a patient is at high risk for an embolic event, said Dr. Black, it makes little sense to perform a cosmetic surgery if that means suspending needed antithrombotics. “But the more important the surgery, the more likely you will proceed. If the patient is having an orbital surgery or a reconstructive surgery with a skin graft or flap for a tumor, the surgical benefit is very high and the risk of significant hemorrhage is also high. In these cases, we would try to move toward discontinuation of the anticoagulant.”

How risky is the surgery? Surgery in the orbit, which is a closed space, is particularly risky, said Dr. Fountain. Eyelid surgery posterior to the septum and orbital surgery are linked with moderate or high bleeding risks and raise the potential for vision-threatening retrobulbar hemorrhage.1 Thus, there’s a stronger argument for suspending antithrombotics in these patients, she said.

Dacryocystorhinostomy is a higher-risk procedure, too, said Dr. Black, but the surgeon has more options to control bleeding, including packing of the nose or the adjunctive use of a laser.

Less risky are superficial skin biopsies or procedures that don’t involve orbital fat removal, orbital tumors, or orbital decompression, Dr. Black said. Bruising and bleeding may increase, but they pose less of a danger. Patients who are nearly blind or who require enucleation are by definition at lower risk.

How high is the ischemic or embolic risk? If antithrombotics are discontinued, will this put the patient at serious risk for an event such as a heart attack, stroke, or DVT? “Cancel the surgery if the patient is scheduled for a lower-lid blepharoplasty while he or she is on Coumadin, aspirin, and/or Plavix [clopidogrel] and just had stents put in 4 months ago,” said Dr. Black. Such patients “don’t need the surgery right now, but they do need the medications,” he said.

Is bridge therapy warranted? Cardiologists will sometimes consider a low-molecular-weight heparin bridge for patients who need surgery that is dangerous if they are on an anticoagulant, said Dr. Black. But “people who are bridged oftentimes bleed just as badly as if they had stayed on their anticoagulants,” said Dr. Fountain. “So I will often tell the patient, ‘If you can’t stop these medications, we will reconsider whether you truly need the surgery. If we go ahead with the surgery, you will have to accept the risk of postoperative bleeding.’”

Dr. Douketis is a coauthor of the first randomized trial to show that bridging is unnecessary. “We found that bridge therapy triples the risk of bleeding, which is the main reason we don’t do it,” he said. “In addition, it doesn’t appear to provide any benefit for stroke prevention because the initial risk is low.”4

In any event, the primary care physician or cardiologist is the person to make the decision regarding bridge therapy.

Special Considerations

Preop counseling. As always, said Dr. Fountain, have a conversation with the patient before surgery about the increased risk of bleeding and risk of clotting.

Preop testing. “We don’t recommend that surgeons use preoperative coagulation blood tests, such as prothrombin time or activated partial thromboplastin time, to check for residual effects and give them the green light for surgery,” said Dr. Douketis. “These tests are not reliable, especially with NOACs.”

Surgical setting. If you’re doing a surgery in a patient who has a much greater risk of bleeding due to anticoagulation, said Dr. Black, it’s advisable to operate in the hospital setting. “But the majority of the time, we use a decision tree that shouldn’t put us at high risk in any setting.”

Type of anesthesia. “Some ophthalmic surgeons employ retrobulbar blocks, which may increase the risk for bleeding due to use of the needle to anesthetize the nerve in the back of the eye,” Dr. Douketis said.

Blood pressure. “High blood pressure is a major risk factor for bleeding, so it’s prudent to monitor the patient’s blood pressure if you’re operating in the setting of an anticoagulant,” Dr. Fountain said. Preexisting hypertension may also be a reason to move these surgeries to a hospital setting, she added. “After surgery, make sure the field is completely dry, with no seepage or oozing.”

Postop counseling. The oculoplastic surgeon should reiterate instructions provided by the cardiologist or primary care physician about when to resume antithrombotics, said Dr. Black. “Remember that a patient with a recent stent or mechanical heart valve may need to start up more quickly, within 12 to 24 hours.”

In addition, Dr. Fountain said, give the patient specific instructions on what to watch for—such as a sudden increase in swelling, an increase in pain, or a decrease in vision—and whom to call if problems appear.

Postop management. To decrease the risk of bleeding, said Dr. Black, the patient should do the following: 1) Keep the head of the bed elevated, 2) refrain from lifting and bending and avoid rubbing the incision site, 3) use ice packs, and 4) apply pressure if there is any oozing or bleeding.

Just as important, said Dr. Fountain, is explaining to patients why you are asking them to do these things. “I have patients who think I’m being overly cautious and can’t imagine missing their Pilates class,” she said, “so I explain that when your blood pressure increases, you put yourself at risk for vision loss.” Patients can usually resume normal activity within a week.

Navigating NOACs

Dabigatran (Pradaxa), approved by the FDA in 2010, was the first NOAC marketed in the United States. Rivaroxaban (Xarelto) and apixaban (Eliquis) followed, and edoxaban (Savaysa) was approved early last year. They are widely used in Canada and the European Union.

How they work. These drugs affect the clotting cascade but have different half-lives and mechanisms of action than do older standbys such as warfarin.1 They are considered to have a more predictable pharmacological profile, be less likely to cause drug interactions, and carry a lower risk of intracranial bleeding than other antithrombotics.

Indications. NOACs are used for prevention and treatment of venous thromboembolism (VTE) and for stroke prevention in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. They are contraindicated in those with mechanical heart valves and severe renal insufficiency.1

Shorter half-life, quicker effect. All NOACs have a similar half-life, but some are more dependent on the kidney for elimination than are others, said Dr. Douketis. In general, NOACs have a half-life of about 8 to 15 hours, versus about 36 to 42 hours for vitamin K antagonists such as warfarin.1 This has implications for when they can be safely stopped before surgery and safely restarted after surgery.

“They may seem benign because they’re taken by mouth once or twice daily, but NOACs are potent pills,” Dr. Douketis said. They work quickly: A peak anticoagulant effect is reached after only an hour or two. He added, “We recommend waiting for at least 24 hours after most surgeries before resuming these medications, especially if a patient is at higher risk for bleeding.”

___________________________

1 Esparaz ES, Sobel RK. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2015;26(5):422-428.

|

Remaining Questions

Without validated guidelines for oculoplastic surgery, said Dr. Fountain, patients have to recognize that if they are on anticoagulants and need surgery, they are at risk—and it’s up to the doctor and patient to choose the least risky option.

In the future, double-blind controlled trials might provide some clarity on this issue, Dr. Black added. “Especially with more anterior eyelid surgeries, we may be unnecessarily stopping these agents or bridging for no reason.”

___________________________

1 Ing E, Douketis JD. Can J Ophthalmol. 2014;49(2):123-127.

2 Lee DW et al. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2010;38(4):418-426.

3 Lai A et al. Br J Surg. 2014;101(7):742-749.

4 Douketis JD et al. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(9):823-833.

___________________________

Dr. Black is associate professor of ophthalmology at Oakland University/William Beaumont Hospital School of Medicine and Wayne State University School of Medicine in Detroit. He is also director of Ophthalmic Plastic Surgery at the Kresge Eye Institute. Relevant financial disclosures: None.

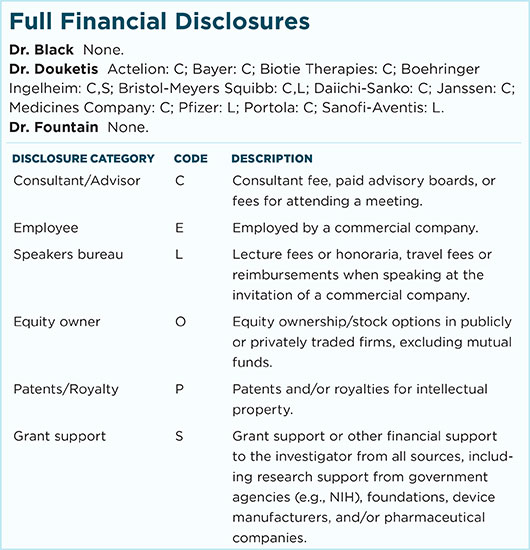

Dr. Douketis is professor of medicine at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada. Relevant financial disclosures: Boehringer Ingelheim: C,S; Bristol-Meyers Squibb: C,L; Daiichi-Sanko: C; Janssen: C.

Dr. Fountain is immediate past chair of the Ophthalmic Mutual Insurance Company and professor of ophthalmology and oculoplastics at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago. Relevant financial disclosures: None.

For full disclosures and the disclosure key, see below.