By Melissa Game Shipley, MD, Mary Fran Smith, MD, and Alan M. Lessner, MD

Edited by Thomas A. Oetting, MD

This article is from September 2007 and may contain outdated material.

Stanley Ogden* was a 75-year-old Caucasian with a swollen eyelid. “It must be from the surgery,” he told us when he came in for his one-month postop visit. He was referring to a routine phacoemulsification cataract surgery that had involved implantation of a posterior chamber IOL in his left eye. After the operation, his wife noticed that his upper left eyelid was swollen and that there was some redness medially. He was otherwise doing very well, so it was decided that this new finding could be monitored.

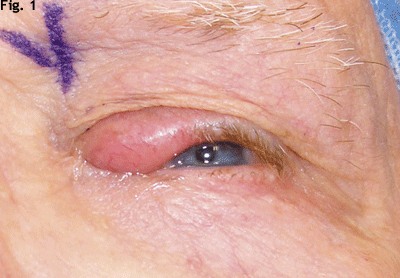

One month later, Mr. Ogden returned to our clinic with persistent left upper eyelid edema and erythema (Fig. 1). He also reported some yellow drainage from the eyelid. His best-corrected visual acuity in the left eye was 20/25 at that time, with normal motility, intraocular pressures and pupillary exam.

Mr. Ogden’s past medical history included anemia and leukopenia, type 2 diabetes mellitus, Bell’s palsy (in the 1960s), chronic renal insufficiency, coronary artery disease, hypertension, basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma and melanoma. His ocular history included pseudophakia and dry eyes bilaterally. He was on multiple systemic medications for his medical problems, and he was a longtime smoker. The review of systems was otherwise negative with the exception of the eye complaint.

The Differential Diagnosis

At the top of the list of differential diagnoses were benign inflammatory disorders, such as severe blepharitis, chalazion, canaliculitis, cellulitis, dacryocystitis and hordeolum. These were deemed the most likely candidates given the sudden appearance of this lesion, characteristics typical of inflammation, presence of discharge and relationship in time to the cataract surgery. However, in the presence of a lid lesion such as this one, it is always important to consider precancerous and cancerous etiologies. The area of focal madarosis, which can be seen in Fig. 1, particularly raised the possibility of a malignant lesion, such as sebaceous cell carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma or lymphoma.

Initial Management

The lesion was first treated with warm compresses, lid scrubs, gatifloxacin and oral amoxicillin. After two weeks on this regimen, there was no improvement in Mr. Ogden’s condition. He was referred for an evaluation by an oculoplastics specialist, who decided to probe the nasolacrimal canal and biopsy the lesion under topical anesthesia in the clinic. Mr. Ogden was unable to tolerate the pain of the lidocaine injection, so the procedure was scheduled to be performed in the operating room under intravenous sedation. On the day of the procedure, it was decided that a biopsy alone would be most appropriate. Even in the preoperative holding area, the patient repeated his belief that the swelling must be related to the cataract surgery.

|

|

WE SCHEDULE AN EYELID BIOPSY. Although Mr. Ogden was pleased with his cataract surgery at one month postop, he was concerned about his eyelid. There was redness, swelling and some yellow discharge.

|

Definitive Diagnosis

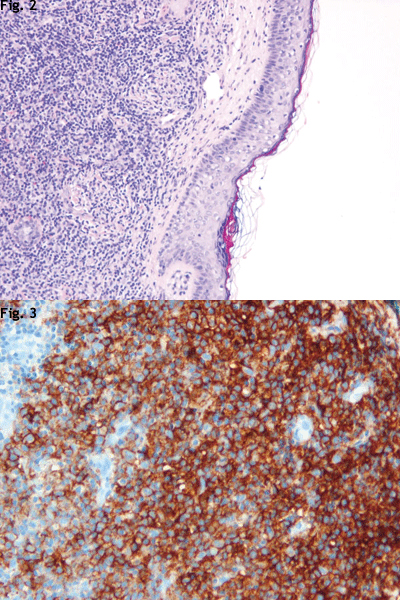

Histological analysis of the specimen showed a dense infiltration of atypical lymphocytes into the dermis that spared the epidermis (Fig. 2). Underlying skeletal muscle was also involved. Immunological staining of the sample indicated strong positivity for the antigen CD20, which is a marker for B cells (Fig. 3). Bcl-2 was also strongly positive, representing a common pathway for follicular lymphomas. A t(14,18) translocation places the Bcl-2 proto-oncogene adjacent to the immunoglobulin heavy chain. This leads to overexpression of Bcl-2, which blocks apoptosis and allows for uncontrolled cell proliferation. Ki-67 only stained 10 to 15 percent of the cells, which indicates a low mitotic index and, therefore, a low-grade malignancy. The final diagnosis was low-grade B-cell lymphoma, most consistent with the follicle center cell type. It was also noted that there was loss of normal zonal arrangement of cells into follicles in this malignant specimen.

At his follow-up appointment, Mr. Ogden was given the new diagnosis of lymphoma, and was informed that further systemic evaluation would be needed. In cases like this, the workup of the patient must include an oncology consultation, complete blood count, a thorough physical examination looking specifically for lymphadenopathy and splenomegaly, and full body imaging. Bone marrow biopsy and lumbar puncture are often obtained in cases like this as well.

When the oncologist saw Mr. Ogden, physical examination revealed no significant findings that would indicate systemic involvement. Although the history of anemia raised the possibility of marrow involvement, it was determined to be chronic, and it was noted that Mr. Ogden was already on epoetin alfa. A staging PET scan was ordered for him, but he declined bone marrow biopsy and lumbar puncture.

Orbital radiation to treat the eyelid lesion was scheduled. The oncologist planned no systemic treatment for the patient, even if disease was found elsewhere, due to the patient’s multiple comorbidities. Rituxan (rituximab) would be considered only if extensive disease were found. (Rituxan is a therapeutic antibody that selectively depletes CD20+ B cells. It binds both normal and malignant B cells and recruits the body’s own defenses to kill the marked cells. B-cell progenitors in the bone marrow survive since they do not yet have the CD20 marker.)

|

|

WE REVIEW THE BIOPSY. A sample of the lesion revealed a dense infiltration of atypical lymphocytes into the dermis that spared the epidermis (2), and immunological staining indicated a strong positivity for CD20 (3).

|

Discussion

Ocular adnexal lymphomas such as this one can present in the conjunctiva, eyelid or orbit. The typical presentation is with a salmon-colored patch or mass. They are often painless and may cause proptosis, extraocular motility defects, diplopia and ptosis.

A lymphoproliferative spectrum exists, which includes reactive lymphoid hyperplasia, atypical lymphoid hyperplasia and malignant lymphoma. All of these can present very similarly and often require a biopsy to be distinguished. Though they can present at any age, ocular adnexal lymphomas most often are diagnosed in the fifth to seventh decades.

In 10 to 17 percent of cases, the condition is bilateral at presentation, and 20 to 40 percent of cases have a history of, or concurrent finding of, extraocular lymphoma at diagnosis.

The majority are non-Hodgkin’s B-cell lymphomas. Most common is the extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma, followed by the diffuse large B-cell and follicular types. About 60 to 80 percent present at stage IE, according to the Ann Arbor system of staging. In this stage, the condition is localized to one extralymphatic site. These stage IE tumors only require orbital radiation of 28 to 40 Grays, whereas disseminated malignancies require systemic chemotherapy. After orbital radiation, it is important for the ophthalmologist to monitor for ocular side effects of the treatment, such as xerophthalmia, corneal ulceration, cataract formation, and retinal or optic nerve head vasculopathy.1

Gastrointestinal tract MALToma is a form of extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma similar to ocular lymphoma but originating in mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT). Gastric MALToma is associated withHelicobacter pylori infection, and eradication of H. pylori with oral medicines has led to MALToma remission. Prolonged antigen stimulation may lead to loss of regulation of B cell proliferation and differentiation. Oxidative damage induced by presence of genotoxic factors, such as infectious organisms, may lead to the gene mutations that allow for the uncontrolled cell growth.2

This concept has been investigated in ocular lymphomas as well. Chan et al. showed that four out of five cases of conjunctival MALToma they examined were positive for H. pylori.3 But Sjo et al. found that all 13 cases of conjunctival MALToma investigated were negative for H. pylori.2 Ferreri et al. looked at Chlamydia psittaci as a potential source for the prolonged antigen stimulation, finding that 80 percent (32 of 40) of the ocular specimens reviewed were positive for C. psittaci.4 Also, two of four patients showed objective response to treatment with doxycycline. Others who have looked at this organism as a potential source of antigen stimulation have shown widely varying incidences of C. psittaci in ocular lymphoma specimens, ranging from 0 to 47 percent. Studies in the Netherlands,5 New York6 and Miami7 found no evidence of C. psittaci in the specimens examined.

In closing, the present case of lymphoma presenting in the eyelid emphasizes the importance of performing a biopsy on all suspicious lesions. It is also important to always take photos for documentation of these lesions. After the initial diagnosis, both eyes of these patients should be followed closely in the long term, as 20 percent of them relapse with disease in the contralateral eye.1

___________________________

* Patient name is fictitious.

___________________________

Dr. Game Shipley is a resident, Dr. Smith is an associate professor and Dr. Lessner is an assistant professor; all three are at the University of Florida in Gainesville.

___________________________

1 Coupland, S. E. et al. Surv Ophthalmol 2002;47:470–490.

2 Sjo, N. C. et al. Ophthalmology 2007;114:182–186.

3 Chan, C. C. et al. Histol Histopathol 2004;19:1219–1226.

4 Ferreri, A. J. et al. J Natl Cancer Inst 2004;96:586–594.

5 Mulder, M. M. et al. Leuk Res 2006;30:1305–1307.

6 Vargas, R. L. et al. Leuk Res 2006;30:547–551.

7 Rosado, M. F. et al. Blood 2006;107:467–472.