Download PDF

The COVID-19 crisis has closed practices and forced ophthalmologists to rethink how to focus their energy. During the week of April 13, down, EyeNet asked seven ophthalmologists for their observations on the crisis. It’s a snapshot from a specific time in global and medical history that changed everything from physicians’ day-to-day routines to their perspectives on life and the meaning of being an ophthalmologist.

Telemedicine

Lisa M. Nijm, MD, JD

Medical Director, Warrenville Eyecare & LASIK, Warrenville, Illinois

Q. How has the pandemic changed your short-term priorities?

As is true for other ophthalmologists, my priorities are to protect my patients, staff, and family. When I learned that the coronavirus was deemed a pandemic, I began rescheduling routine visits in an effort to protect my patients and staff. Initially, I thought this would be for just a few weeks. However, after the Academy made its official recommendations, I quickly implemented telemedicine as a way to continue to provide care.

Q. What are you doing now that you would not have done otherwise?

We did not have telemedicine available prior to the pandemic, primarily due to the restrictions from CMS. Lifting those restrictions allowed us to provide this innovative care to patients.

Presently, we touch base with each patient on the schedule and determine whether it’s a routine visit that can be postponed, a visit that is suitable for telemedicine, or a visit requiring urgent follow-up. The dynamics of a telemedicine visit may require creativity from both physician and patient to acquire as much information as possible. For instance, I have had patients check each eye individually by focusing on their TV or another object in the room if an eye chart could not be printed. When necessary, I have requested that a patient send a close-up of his or her eye for a more detailed external exam.

Understandably, not all cases are ideal for telemedicine; however, I can provide care for many of my established patients with common external conditions such as dry eye, chalazion, or recurrent erosion. I have also found it useful as a more sophisticated screening tool to determine whether a patient needs to be seen emergently. Finally, I value telemedicine visits as an opportunity to have a more in-depth discussion for conditions such as dry eye treatment or lens choices in cataract surgery. This approach allows patients greater time to digest the information so that we will be ready to proceed with appropriate treatment once elective visits are resumed.

Q. What are the biggest rewards?

I’ve found telemedicine to be incredibly valuable, and I think my patients have found a lot of value in it as well. A silver lining during this crisis has been the ability to provide greater access to care for patients with the potential to move this technology forward.

My favorite telemedicine app currently is Doximity as it has a HIPAA-compliant video capability that is relatively straightforward to use. Once you enter the patient’s phone number, it sends a text with a link to the patient’s smartphone. Within a few clicks—voilà—I receive a text message that the patient is ready to be seen. I have also been working with colleagues on a step-by-step guide to help patients take and submit high-resolution smartphone photos for telemedicine visits.

Q. What are your greatest concerns?

Telemedicine is not the same as having the patient in the office. Further, some patients don’t have video capabilities; therefore, they are limited to phone consults. But I do feel it is the best way we can continue to care for patients remotely while keeping everyone safe during this crisis.

Relaxing the guidelines and providing adequate reimbursement are key to encouraging greater utilization of this technology. My hope is that CMS maintains the availability of telemedicine past this crisis. I can see it as an option for enhancing access to care, especially for patients who cannot make a visit due to unforeseen circumstances such as a winter snowstorm.

Q. What are your biggest challenges day to day?

Being an MD and JD, I should mention that it is prudent to be aware of the medicolegal risks and the liability associated with telemedicine. You must include appropriate documentation in the chart, including informed consent and all elements of the visit as you would for any in-person patient encounter. The Academy has provided guidelines to assist with documentation,1 and OMIC has recently released a telemedicine consent form.2 These guidelines will ensure that you have proper documentation not only for reimbursement purposes but also to minimize potential risk exposure.

Q. What do you see as the impact of what you are doing?

Telemedicine is a great way to help patients while ensuring safety. Importantly, it can help assess urgent situations. In fact, for two of my patients—one with a corneal ulcer and the other with corneal edema—the telemedicine visit was the deciding factor in recommending an urgent in-office visit and likely saved both patients’ vision.

Q. What’s your perspective on the pandemic?

This is certainly a challenging time for everyone, but it’s a time-limited phenomenon—we will overcome this disease. I am consistently inspired by the resiliency of the human spirit and the great things we accomplish by working together.

Time is precious. This is an opportune moment—likely the only one we will ever have in our careers—to sincerely step back and reevaluate our personal and professional lives. I would encourage my colleagues to be cognizant of that—to pause and look for ways to nourish the mind, body, and soul.

From a practice perspective, this is an excellent opportunity to evaluate what we do well and what we can do better. Are there new technologies or techniques that we might implement now to continually improve delivery of care? It’s a chance to turn this into a time of growth and truly see how we can do better for our patients, our practices, and the people around us who matter most.

Q. What are your thoughts on being an ophthalmologist during the COVID crisis?

I can’t tell you how many ophthalmologists I have spoken to who tell me they miss their practice. We miss our patients, our staff, and the amazing work we are blessed to do. It is a privilege to be an ophthalmologist. I fully believe that after this brief pause, we will return to our clinics with an even greater passion for the patients we care for and the work we love to do.

___________________________

1 aao.org/practice-management/news-detail/coding-phone-calls-internet-telehealth-consult and search for “documentation.” Accessed April 24, 2020.

2 www.omic.com/telemedicine-consent-form/. Accessed April 24, 2020.

|

|

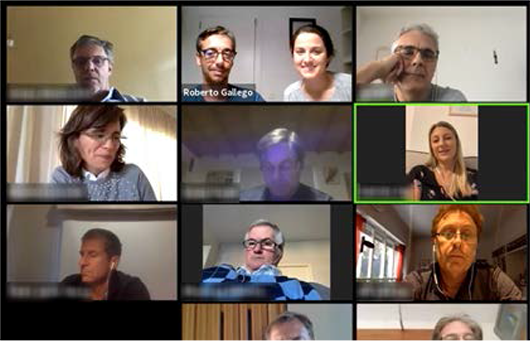

VIDEO VISIT. A patient’s perspective of a video visit with Dr. Nijm.

|

Online Education

Roberto Gallego, MD, PhD

Unit of Macula, Clínica Oftalvist, Valencia, Spain

Q. How has the pandemic changed your short-term priorities?

With the lockdown in Spain since March 15, I have had the opportunity to spend much more time than usual with my wife and son. This is the first time in years that this has been possible without busy clinics and travelling to meetings. I feel that we were living on a hamster wheel while barely looking into our personal priorities. This may change significantly from now on.

Q. What are you doing now that you would not have done otherwise?

As clinicians, we are devoted to patient care but also to education. Since the lockdown started, I have had the opportunity to arrange several webinars, with the aim of being helpful to colleagues in Spain and Latin America. I have used Facebook Live for a half-dozen seminars, with a live attendance of 150-200 people, then shared via YouTube the recorded presentation. During two question-and-answer sessions on Instagram Live, I consulted with colleagues about specific clinical cases. I also had the opportunity to record an informational retina video for patients, which now has over 100,000 views.

In addition, several associations have arranged online webinars. My colleague, and charming wife, Dr. Rosa Dolz-Marco and myself joined the Sociedad Peruana de Oftalmologia and the Sociedad Argentina de Retina y Vitreo for these events. We are both medical retina specialists, so we have tried to expand the knowledge on optical coherence tomography and multimodal imaging interpretation of retinal diseases, mainly age-related macular degeneration.

In addition, I have been invited to several online seminars or discussions about retina management during the coronavirus outbreak. This time has been busy, but I am glad to keep pushing for medical education in the absence of in-person meetings.

Q. What are the biggest rewards?

Via the webinars, I have taken these challenging days as opportunities to grow the network (virtually) among Spanish-speaking retina specialists. It is gratifying when people whom you have never met thank you because they can better understand one of their clinical cases. I am sure that these webinars will have an impact on patient care when we are ready to go back to work.

Q. What are your biggest challenges day to day?

The challenges are significant. As a medical retina physician, I care for patients with neurodegenerative macular diseases. These are typically patients aged 65 and older, meaning that they are at higher risk for complications due to COVID-19 infection. But interrupting their intravitreal injection therapy for a number of weeks may preclude further functional improvement. We call each patient to provide clear information about their situation and help them understand the balance between COVID infection risks and severe irreversible vision loss. The decision about whether to come to the office for treatment should always be made by the patient.

Q. What do you see as the impact of what you are doing?

I think that nowadays the relevance of providing accurate information for patients is essential. Using phone calls for each case seems like the best approach. Doctors are the best option to make those phone calls, and patients are thankful for them.

Q. What’s your perspective on the pandemic?

Our professional and personal lives will change completely. We won’t be able to have crowded waiting areas in our facilities anymore. At least for several months, we may not have opportunity to attend meetings. It seems rational to assume that this may also apply to leisure activities with friends and family. We are facing a new era, like our ancestors did so many other times during history of mankind. And life goes on. Our attitude and adaptability will be determinant.

|

|

WEBINAR. Dr. Gallego takes part in an online symposium.

|

Emergency Department Volunteer

Kyle J. Godfrey, MD

Assistant Professor of Ophthalmology, Weill Cornell Medicine and NewYork-Presbyterian, New York, N.Y.

Q. How has the pandemic changed your short-term priorities?

The pandemic quickly forced me to think in units of hours and days instead of months and years. As a new faculty member, my priorities had been building my clinical practice, research team, and educational efforts. My eyes were focused down the road on things like our new multidisciplinary, endoscopic orbital surgery course. Suddenly, as COVID-19 swept through New York, we lost our sense of horizon. My priorities simplified and my focus sharpened on each day. I prioritized maintaining my health and finding creative ways to engage, support, and educate our community. Substituting long-term vision for short-term focus has helped me put one foot in front of the other and keep moving forward. I have also tried to practice daily gratitude for my health, for the health of my family, and for having a job that allows me to help others.

Q. What are you doing now that you would not have done otherwise?

In addition to telemedicine, virtual lectures, and limited emergency orbit and oculofacial surgeries, I am volunteering as an attending physician in the emergency department (ED). In this new role, I am caring for COVID-19 and appropriate general emergency patients to help decompress clinical volume. This effort is supporting and bolstering the ranks of emergency clinicians who have been tirelessly and courageously caring for the influx of sick patients at multiple hospitals.

Q. How did you get involved?

As the clinical volume surged in New York, our chairman asked for volunteers to support the hospital mission, and I agreed to help. At that time, the need was in the ED. Although I was initially intimidated by the thought of returning to an emergency medicine role, the support I received made for an effective transition.

Q. What are the biggest rewards?

Without question, the gratitude of my new emergency medicine patients and colleagues means a lot. The reception I receive each day in the ED and in our hospital—applause, food donations, chalk messages on the sidewalk, notes from patients—provide a tangible sense of purpose and solidarity. The coordinated hospital response has also been a reminder for me that medicine is a team sport. In ophthalmology, we often function in small, highly specialized units at some distance from the rest of medicine. However, being a part of the hospital’s massive, coordinated response at the front lines of this crisis reminded me how much more powerful and effective we can be when collaborating, communicating, and working together for a common purpose. To see our hospital system not just survive but also take care of our community at the highest level has been a huge reward, and I know it has set example for other departments around the city and country.

Q. What are your greatest concerns?

My greatest concern had been that at the peak of the local curve we would not have sufficient resources or space to care for everyone who came through our doors. Thankfully, due to the exceptional efforts and leadership at our hospital, this did not happen. We have been well protected and well organized, and we have been able to care for everyone with a remarkably high level of success. Secondarily, I also empathize with any concerns our residents and fellows are feeling about their own training experiences (although none have expressed anything other than a desire to help). However, our residents and fellows are fortunate to have a dynamic and high-volume learning environment, and I am confident that they will graduate as competent and well-trained clinicians and surgeons.

Q. What are your biggest challenges day to day?

Although I miss operating and the daily interactions with my colleagues in our department, I have enjoyed the new challenge of clinical work in the ED. Quickly transitioning to a new field pushed me cognitively, physically, and emotionally, but it has been tremendously rewarding. From a clinical perspective, the COVID-19 treatment algorithms have been effective in guiding our coordinated, resource-efficient response, and they have contributed to our success. Additionally, the support of the staff, including technicians, nurses, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, residents, and attending physicians in the ED has been crucial to my ability to care for these sick patients.

Q. What do you see as the impact of what you are doing?

I am only playing a small role in a large and complex group effort, but I think standing shoulder to shoulder with my new ED colleagues helped reinforce for them that no department, clinician, or patient will be left behind, and that we are all pushing back against the tide of this disease together.

Q. What’s your perspective on the pandemic?

I think the perennial importance of positivity, gratitude, and service have emerged for me. Although the losses are overwhelming, I think we can all find reasons to be positive. This perspective empowers us for the important work ahead. From a place of gratitude, I think we are all capable of contributing something. I have been inspired by the creative ways people have found to serve others and contribute. I am also continually inspired by the work of all essential employees who have kept our hospital, city, and country going. From transit workers to grocers to police officers, I have tried to say thank you at every opportunity.

Q. What are your thoughts on being an ophthalmologist during the COVID crisis?

From a medical perspective, a crisis of this magnitude requires us to contribute our full effort, at the top of our training, to the areas of greatest need. Our first impulse must be to help in every way possible. Although we are fortunate to have highly specialized microsurgical skills that allow us to prevent and cure blindness, we were first physicians trained in the diagnosis and treatment of systemic illness. We have more to offer our patients than we may initially believe.

|

|

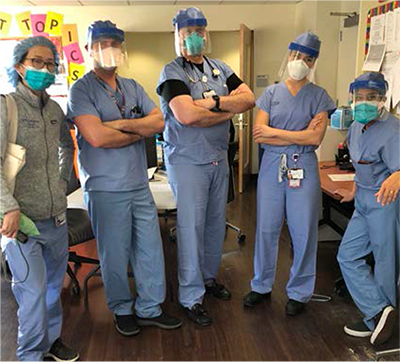

IN THE ED. Of his experience in the emergency department at New York Presbyterian Hospital, Dr. Godfrey notes that caring for the community at the highest level has been a huge reward.

|

Volunteer on the Floor

Joel S. Schuman, MD

Professor and Chairman of Ophthalmology and Director, NYU Langone Eye Center, NYU Grossman School of Medicine, New York, N.Y.

Q. How has the pandemic changed your short-term priorities?

The pandemic certainly shifted focus for many people in a variety of specialties as well as for those outside of medicine. But in medicine, it really put the emphasis on saving lives.

Another change is within the financial arena. Financial well-being is a core focus on the business side of ophthalmology, and the aphorism in academic medical centers is, “No money, no mission.” But the pandemic really shifts the priority to maintaining health. That’s why all of us are ratcheting down our clinical practices in ophthalmology—to reduce risks to ourselves, loved ones, patients, and staff.

We’re now seeing about 20% of our normal volumes in our clinical practice. As department chair, I made a decision early on to only see patients in the office who had urgent or emergent problems, as recommended by the Academy. These patients receive whatever care they need. But by coming into an office or a hospital where there is a higher concentration of people with COVID-19, they’re also exposing themselves to a greater chance of developing COVID-19, and that has added to the kinds of discussions we need to have with our patients.

Q. What are you doing now that you would not have done otherwise?

Several of my faculty and I are working on the inpatient medical floors at NYU Langone Health Tisch Hospital. Nearly 100% of the patients we’re caring for have COVID-19 pneumonia, and a certain percentage of them end up on a ventilator in the ICU. This is serious business. We see people who one day seem to be relatively stable or even seem to be getting better, but the next day, they rapidly deteriorate and are struggling to breathe.

The work we’re doing on the floors as general medical doctors is similar to what I did as an intern in New York 35 years ago. When I was taking care of patients in 1984 and 1985, AIDS was growing in New York City. It was another disease we didn’t really understand, and people were very afraid. But I didn’t know one person in the hospital who shirked his or her responsibility. Everyone stepped up and took care of patients.

Now with COVID-19, we have a virus that is airborne and very contagious, but fortunately has a much lower mortality rate—more like ~1%, depending on the country and risk factors. Many ophthalmologists in my department, as well as many of our trainees, have volunteered to take care of these patients. Rather than saying, “I didn’t sign up for this,” everybody is basically saying, “Put me in, coach. I’m ready.”

Q. How did you get involved?

I’m married, and I have three adult kids. My wife, who is an attorney, was nervous about the prospect of my taking care of patients on a medical floor where everyone has COVID-19. But when our institution asked for volunteers, I could not in good conscience ask other people to do something that I wouldn’t do myself. I felt a sense of responsibility not only to the patients directly, but also to my faculty. When the time came, I had my family’s full support in volunteering to work the floors.

Q. What are the biggest rewards?

There is the intrinsic reward of helping people, of lending a hand. The other reward is something that I remember from my internship, which is a sense of camaraderie. All of us who work together as teams on the floors have a sense of closeness because we have the opportunity to face and do something extraordinary together. This shared intensity is special.

Q. What are your greatest concerns?

I really don’t want to make my family sick. My middle son moved in with us during the first week of the quarantine. When I come home at the end of the day, he, my wife, and my dog all barricade behind closed doors. Although my wife would like to hose me off in the street, I live in Manhattan, so that would be weird! Instead, I go straight to the shower; there’s no contact until that’s done and I’m in fresh clothes. I take every precaution at work and at home so I don’t bring SARS-CoV-2 to them.

Q. What are your biggest challenges day to day?

These are 12-hour shifts and at the end of the day, I pick up and do my day job as an ophthalmologist and department chair. That certainly is a challenge.

There is also the stress of taking care of people who might die, which is not something we usually deal with as ophthalmologists. It is challenging, but the patients are the ones who are really suffering.

Each day, we do everything we can to support people with COVID-related problems, predominantly pneumonia. I’ve had patients with all kinds of virus-related issues such as cytokine storms, hypotension, hypoperfusion, microvascular hypercoagulability, stroke, and multiorgan failure.

We spend most of our time following labs on patients and assessing how they are doing clinically with the disease. For example, how much inflammation do they have, and do they need more medication to address it? Are they stable or going downhill? Are they doing okay with everything we can do for them on the floor, or do they need to be in intensive care or on life support? Are they ready to go home or to rehab? That’s pretty much our day-to-day routine.

Q. What do you see as the impact of what you are doing?

Working as general medical physicians, I feel the whole team is helping to save people. We’re another pair of hands and another set of eyes to watch these patients, and if they’re getting into trouble, we can move them into more intensive care.

Although we’re using a muscle that we don’t use every day—one many of us haven’t used in a long time—we do have a special set of skills. We went to medical school and we know how to deliver medical care.

Q. What’s your perspective on the pandemic?

This disease is highly transmissible and deadly for some, and it has shut down the global economy. It makes you realize what a fragile thing life is, especially when you’re taking care of patients with this disease.

I recently rewatched “Outbreak,” and there’s a scene in the movie where Dustin Hoffman’s character says, “Something 1 billionth our size is beating us.” And that’s what we’re dealing with. It’s very humbling.

Q. What are your thoughts on being an ophthalmologist during the COVID crisis?

Being on the general medical floor has reinforced that my subspecialty choice was right for me. With COVID-19, we’re very often providing supportive care, helping keep people alive while they try to beat the disease. But we don’t know how to cure it. In ophthalmology, we can make people better, and we do it regularly. We can help restore patients’ sense of sight and help to improve their quality of life. We have a pretty great profession. When the pandemic ends, I will be happy to get back to it full time.

|

|

READYING FOR THE FLOOR. From left to right, Eleanore Kim, MD, Zachary Elkin, MD, Joel Schuman, MD, Irina Belinsky, MD, and Vaidehi Dedania, MD, meet before they see COVID-19 patients.

|

Educating Trainees

Paisan Ruamviboonsuk, MD

Chairman, Department of Ophthalmology, Assistant Director, Rajavithi Hospital, Bangkok, Thailand

Q. How has the pandemic changed your short-term priorities?

In early February, my hospital in Bangkok had just opened a new 25-story building and new eye clinic. Moving an eye clinic with more than 50 units of full-function eye instruments was not easy, but it went quite smoothly. For about four weeks, we were able to see the same number of patients as in the old clinic, around 500-600 patients a day.

Then, the number of COVID-19 cases began to accelerate, forcing the government to impose a state of national emergency. Our department decided to adjust services and training. Our short-term goal was to find a balance between the risk of viral contamination in our facilities, the risk of infection among eye care personnel, and the eye care needed for our patients, including ophthalmic education for our residents and fellows.

We postponed almost all elective cases in the outpatient department (OPD) and OR. The number of patients dropped to around 30-40 a day in the OPD, and we operated on only two or three cases a day, compared with around 20 cases a day before the pandemic.

Q. What are you doing now that you would not have done otherwise?

Our country has been fortunate to not have too many cases of COVID-19. However, we needed to adjust our ophthalmic training program because we now have fewer eye patients and scarcer resources. It is challenging to use limited resources for training in ophthalmology, especially since we don’t know when this pandemic is going to end. As currently organized, I think this unusual training program using limited resources should work for at least three or four months.

Q. What are the biggest rewards?

This is a difficult time for our residents and fellows. The longer the lockdown, the less they are able to learn from real clinical experience in eye clinics or the OR. The biggest reward would be maintaining high-quality training despite the limited resources. Becoming a confident ophthalmologist would be a reward for each of the trainees, especially those who graduate this year.

Q. What are your greatest concerns?

For ophthalmology trainees, it’s important to gain both medical and surgical skills. During the pandemic, trainees can study interesting cases in our collection of departmental presentations. However, gaining surgical skills is more difficult. Imagine how many cases a resident or fellow could normally operate on during the course of several months. On lockdown, this cannot happen. Learning with simulators may be better than nothing. But learning about cases from slides or simulators is not comparable to learning in real clinical situations.

Q. What are your biggest challenges day to day?

We have not yet faced the biggest challenges related to COVID-19. Timely termination of the lockdown might be what everybody dreams of, but in ophthalmology, the biggest challenge may come after this pandemic is over. Ophthalmic services around the world may face a flood of cases, including many more challenging cases, some of which we might have been able to manage better if we had seen them sooner. For example, this includes cases of complicated retinal detachment, proliferative diabetic retinopathy, or diabetic macular edema. We need to prepare for them.

For trainees, the flood of cases may mean more time for service but less time for learning. We need to prepare for fewer learning opportunities not only during this crisis but also after it ends.

Q. What do you see as the impact of what you are doing?

Ophthalmic training is very important for producing new generations of qualified ophthalmologists. They are our future.

Q. What’s your perspective on the pandemic?

In their own way, everyone will learn a great deal about life during this crisis, for example, about society, the environment, politics, ideology, and morality. How will individuals’ thoughts and experiences join to shape the world in the future? Will the world be more divided or more coherent? I still believe in the latter. I don’t think we can deal with a pandemic like this by creating walls on the borders of countries. We are better off acting as a single country, the “world’s country.”

Q. What are your thoughts on being an ophthalmologist during the COVID crisis?

As ophthalmologists, we are quite fortunate that we don’t have to treat patients with COVID-19 directly as do infectious disease specialists, pulmonary specialists, or emergency room physicians—all of whom we really honor. However, we can choose to volunteer to assist in screening or treating these patients as some of our ophthalmologist colleagues are doing.

Because each ophthalmologist had different roles before this pandemic—as clinicians, researchers, educators, teachers, or trainees—each may be affected by this crisis in different ways. Some may still be able to work in their own areas with limited resources. At a minimum, simply keeping ourselves safe by not contracting the disease may be a great contribution. The world will still need healthy ophthalmologists to prevent blindness after this crisis is over.

|

|

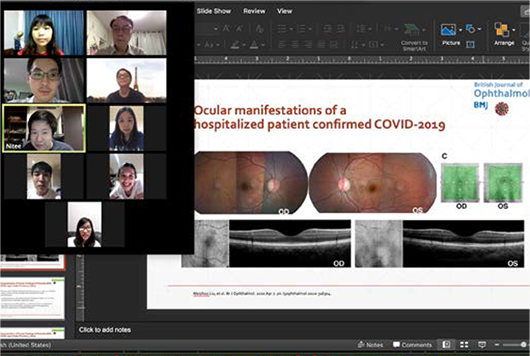

ONLINE TRAINING. Dr. Ruamviboonsuk hosts an online training session.

|

Following Patients Discharged From the ED

Ashley R. Brissette, MD, MSc

Weill Cornell Medicine and NewYork-Presbyterian, New York, N.Y.

Q. How has the pandemic changed your short-term priorities?

I think we were all used to planning extremely far ahead. Moving toward taking things more day to day has been a big change for me. My surgical and clinic schedules were booked a few months out, and now I have to tell my patients I don’t know when we can go back to regular visits or nonemergent surgery. In the short term, I am focused on making sure my patients who need close continued care are getting access—whether via telemedicine or an in-person visit if truly needed. As well, my research studies are currently on hold.

It was difficult when many of our conferences and meetings were cancelled. It’s something I look forward to every year as a way to connect with colleagues and for continuing education. But it’s been incredible to see how ophthalmologists worldwide are starting to turn to online education like webinars. It’s been an amazing way to connect us globally and I am getting to learn so much about my colleagues both nationally and internationally. I feel like everyone is really coming together to ensure that we are still learning and connected.

Q. What are you doing now that you would not have done otherwise?

The first week after our offices and ORs closed, I spent a lot of time doing phone and telemedicine visits with my patients, especially those who were post-op or needed close follow-up. After that initial week, I felt a little lost. I wanted to help and didn’t know in what capacity I could offer help. Our chairman asked if anyone would be willing to volunteer for “redeployment” to other areas of the hospital to help. So now I am helping with the ED at our institution.

I work four shifts per week and have several tasks. One of the most interesting is that I’m assigned a list of patients who were discharged from the ED with COVID+. I do a video chat with each patient to assess how he or she is doing. I have the patient show me the pulse oximeter readings, and then the patient walks around at home, and I recheck the vital signs. I also have the patient put hand to chest, and I guide him or her through measuring the respiratory rate. I also assess the single breath test and use of accessory muscles for breathing. Based on these results, I determine whether patients need to come back to the ED or if they are okay to stay at home. I also review supportive care measures that they can do at home.

Q. What are the biggest rewards?

Feeling that I have a purpose in all of this has been extremely rewarding. Especially being in New York City where we were hit the hardest in the country, it was a way to give back to the city. I think we have a duty as health care providers, and it’s been amazing to see how the medical community has come together to support each other. We are no longer operating within our silos of medical care—we all have a shared goal of getting our patients through these trying times.

Q. What are your greatest concerns?

My biggest concern was that, since it had been a long time since doing general medicine, I wouldn’t really be useful. But on my first day, there was an orientation, and the hospital has very strict protocols for seeing and examining COVID patients. In addition, the MDs, nurses, PAs, and other hospital staff are very kind and helpful. Having the support of my institution and hospital and having the protocols really helped.

It may seem surprising, but I’m not too concerned that I will get COVID. Part of me thinks I already had it because I saw so many sick patients in the weeks leading up to the shutdown. And, luckily, there haven’t been any problems with PPE here.

Q. What are your biggest challenges day to day?

Balancing the telehealth visits with my own patients, the hospital shifts, teaching for the residents and fellows, and attending online webinars. I think I am as busy as ever, just in a different way. I’ve accepted that I can’t grow my personal practice at this time and instead am focusing on education and helping the COVID efforts.

Q. What do you see as the impact of what you are doing?

I think I was eager to volunteer because I wanted a sense of purpose during this time. None of us could have imagined how much something like this would affect our practices and our lives. So, in these trying times, rather than waiting to see what would happen, I wanted to continue to grow as a physician and person. I want other ophthalmologists to know that they shouldn’t be scared if they are called upon to help in their hospitals.

Q. What’s your perspective on the pandemic?

I think that it’s important to have a growth perspective during this time of uncertainty. It’s natural to be nervous or to panic, but it’s crucial to accept our situation, live in the now of our new reality, and plan for what’s next. I really think that this will also change the way we practice medicine in the future. As we and our patients are getting more comfortable with telemedicine, it might play more of a role in certain situations going forward. I’m interested to see how this will change the practice of ophthalmology in the future.

|

|

COVID-19 FOLLOW-UP. Dr. Brissette volunteered for “redeployment” to other areas of her hospital. Now she is following COVID+ patients who have been discharged from the ED.

|

Adapting With Flexibility

A. John Kanellopoulos, MD

Medical Director, The Laservision.gr Research & Clinical Eye Institute, Athens, Greece, Clinical Professor of Ophthalmology, NYU Medical School, New York, N.Y.

Q. How has the pandemic changed your short-term priorities?

There has been a dramatic change. From a starting point of 30 associates, we have “leaned” down to three people for an emergency reception, technician, and optometry crew, as well as one ophthalmologist with physical presence at the center and seven more working from home. We alternate personnel on a two-week basis for quarantine reasons and to enhance social distancing for the rest of the team. We started taking these measures two weeks before the lockdown in Greece on March 16.

We are lucky that our electronic medical record system and our phone center can be accessed remotely. Most issues can be taken care on the phone, by video call, and even email, sometimes with patients sending in photos of their eyes. In person, we are seeing only urgent cases such as trauma; vascular events; active or recurring CNV; retinal detachments, tears, or other urgent retina procedures; anti-VEGF injections for macular degeneration; and urgent glaucoma procedures. The practice has a protocol for this purpose (see “Protocols for COVID-19,” below).

Q. What are you doing now that you would not have done otherwise?

We are employing extensive protective measures in the practice. For example, we designed and have been using a do-it-yourself slit-lamp breath shield since the beginning of February (https://youtu.be/jK2pwq8_bLA). In addition, we have organized an IOP drive-through checkup service with a Tonopen and have instituted extensive telemedicine and infectious disease training for our staff (use of PPE, gear-on and gear-off care, etc.).

Of course, like almost everyone else, we are resorting increasingly to electronic forms of communication. I had an international meeting at the beginning of March via WebEx, and doctors from every continent participated. It was a two-day meeting, four hours a session. I must admit that the meeting was by no means inferior to what it would have been if we had all physically traveled to a certain location. On the negative side, I think that most of the conventions this year have been or will be cancelled. That is a very big disadvantage for continuing medical education and for sharing our clinical experiences with colleagues throughout the world, as we were used to doing.

As for academics, one positive change is that my duties as a clinical professor of ophthalmology at NYU School of Medicine formerly required me to travel to New York several times a year to work with the residents. Now, most of this work is being done electronically, even by the faculty in New York. For example, the morning lectures are presented via WebEx, and I am very excited and grateful that I can have a more active role in this.

In addition, I am catching up on writing and reading. In fact, I have already submitted five papers that were long overdue! And I’ve been exploring the ISRS Multimedia Library, past meeting materials, and the Journal of Refractive Surgery on ISRS.org, the website for the International Society of Refractive Surgery, the refractive surgery arm of the Academy.

Q. What are your greatest concerns and rewards right now?

One concern is that a lot of significant visual complaints may not be treated with the appropriate care and attention when weighed against the dangers of not enforcing social distancing. Of course, we are working hard to triage and screen patients over the phone. I hope that we will return in some way to offering more in-depth and more comprehensive care to our beloved patients.

On the upside, it is encouraging that our extreme measures and the country’s early lockdown seem to have paid off so far. We have reached single-digits of daily new COVID-19 infections, under 65 active ICU cases, and a cumulative 131 reported fatalities so far in Greece (as of April 26). This is probably an all-European record, especially considering the strong tourism and travel activity in Athens and all of Greece throughout the year.

Q. What are your biggest challenges day to day?

Obviously, there are significant financial challenges when a busy, productive practice comes to a near standstill. Beyond that, I think the biggest challenges are to stay proactive, remain emotionally stable, take advantage of this time to tackle some things that have been neglected—and, of course, to retain a healthy lifestyle.

It may be months before we can hope for any type of “normality,” but I think that people as a whole have proved that in times of adversity, they are very patient and compassionate and have the perseverance to pull through.

Q. What do you see as the impact of what you are doing?

I think that offering the best possible care under the circumstances provides security and reassurance to our patients. In addition, continuing medical education, research, and academics are greatly important.

Q. What’s your perspective on the pandemic?

It is interesting and, at the same time, surreal to see what our everyday life has come down to. I recently took a walk in the center of Athens and realized that life really has come to a standstill. It is the beginning of spring, and the weather has gotten better; nevertheless, the streets are almost empty, with just a few people—in maximum parties of two—walking around at impressive distances from each other. And all commercial businesses are closed, except for news kiosks and some grocery stores.

I think that when we see this and reflect on our lives before the pandemic, we begin to realize that we can live our everyday life with much less, and we can organize and prioritize our life to attain a better balance between our physical health, our emotional and family time, and of course, our professional time. Too often, the boundaries among these are stretched, with our professional life taking over disproportionately. I’m sure that I’m not alone in pondering these points, and when this ordeal is over, I hope that we will apply these lessons to achieve a more productive and happier lifestyle for the future.

Q. What are your thoughts on being an ophthalmologist during the COVID crisis?

In a world that has long seemed to value the talent and abilities of those who are most likely to trend on social media (for example, professional athletes, entertainers, and “famous” people), I think that this pandemic underscores that medicine may be the most important science and profession that humanity has developed. Every aspect of scientific work is obviously important, but during this time, doctors, nurses, hospital staff, and all health care providers “rule”!

It may sound egotistical, but it does fulfill me, as a physician, to be part of this, given the work and sacrifices I have made since my late teens in order to pursue the difficult road of medical education, residency training, multiple subspecialties, and a very demanding professional life.

Of course, I realize that not being a pulmonologist or an infectious disease expert or a critical care expert on the front line of treating COVID-19 patients—and my heart goes out to all these colleagues—makes me less important. But I do feel that the world will come to better understand the value, the dedication, and the daily sacrifices that physicians and health care workers contribute day in and out in order to improve other people’s lives. It gives me a significant sense of fulfillment, as an anterior segment eye surgeon, that I can still offer my expertise 24/7, as well as my sense of commitment, to all the wonderful patients I have been blessed to care for even during these very difficult times.

|

|

ATHENS ON LOCKDOWN. In his now-quiet city, Dr. Kanellopoulos takes time to reflect.

|

___________________________

All Things Coronavirus. Visit aao.org/coronavirus. It is chock-full of clinical, practice management, and patient education news, information, and resources to help you handle the turbulence of the pandemic.

Protocols for COVID-19

April 29, 2020

This global pandemic of COVID-19 is engulfing all functions and factions of our daily lives.

In an effort to compose my thoughts and direct my actions in this time of crisis, I consulted the websites of the European and U.S. Centers for Disease Control, the World Health Organization, and the Academy.1-4 I was pleasantly surprised that the guidelines they laid out were similar to the measures we have enforced in our practice.

The key concepts of the guidelines are: 1) limit how germs can enter a facility; 2) isolate symptomatic patients as soon as possible; 3) protect health care personnel; and I will add my own 4) exercise caution and use protection for our families.

Because of the significant shortage of PPE and disinfecting equipment as well as the 14-day incubation period for the virus, we split our staff into two shifts. The first shift works for two weeks, and then is off for two weeks while the second shift works.

We also carefully triage our patients using telemedicine. For example, we ask patients to use their smartphones or camera to provide images of their ocular symptoms. In this way, we can eliminate having patients come into the office for minor issues. Only those that warrant examination are asked to come in. Under this new normal, we postpone routine follow-up appointments that can be evaluated later on.

All prescription refills are done electronically or over the phone, and we recommend that all glaucoma patients purchase a three-month supply of their drops.

Under the same policy we are limiting follow-ups in refractive surgery and asymptomatic postcataract surgery patients as long as the latter do a regular Amsler grid check and call us ASAP if they notice any changes or new symptoms.

All scheduled elective refractive surgery and cataract procedures have been postponed until further notice. It looks like we will be returning slowly to routine evaluations and procedures over the next few weeks.

Patients who must visit us are triaged carefully. That is, recent travel and personal and family medical history are obtained, and we specifically ask about the symptoms associated with COVID-19 (sore throat, coughing, sneezing, and/or fever). We use an infrared thermometer or an industrial remote thermometer that can scan a patient’s forehead from 1 foot and 3-6 feet, respectively, although we now know that measuring body temperature is not an efficient screening tool.

We provide face masks, gloves within individualized plastic bags, and disinfecting gel to all patients who come in. We show patients how to place and remove the plain surgical mask, which we invariably augment with a piece of paper tape to secure it over the nose. In this practical video, we attempt to familiarize our patients with “gear-on” and “gear-off” PPE (https://youtu.be/gy-LpEoD114).

Patients’ escorts are seated in our outer waiting area and spaced at least 2 meters (6 feet) apart, or they may wait outside our office. We communicate with them via live videoconferencing on their smartphones should they need to be part of the exam. Of course, those patients requiring special assistance may be accompanied by their escorts.

Outside of our restrooms, we provide replacement gloves and, of course, disinfectant gel. The waiting room coffeemaker, refreshment refrigerator, and water dispenser have been moved behind the front desk. Before serving patients these items, staff make sure that patients can see that they have sanitized their hands. Additionally, we’ve installed a makeshift nylon shield for the opening in our front-office counter.

In the exam rooms, all slit lamps have been retrofitted with an accessory breath shield made out of a cellophane sheet. Here is a do-it-yourself video: https://youtu.be/jK2pwq8_bLA.

We try to limit contact with charts and papers, which is easy in our facility because we use electronic health records and base our entries on the pre-exam phone call with the patient, the in-office patient conversation, and the video of the slit-lamp exam. This information can be transmitted electronically to the physician who can—in almost 95% of cases—evaluate and care for the patient from a distance.

All procedures that do not require direct patient contact, such as explaining procedures, billing, and informed consent are done via live videoconferencing, either within the office or after the patient has left.

After each patient leaves the room, the room is disinfected, and all gloves and gowns are disposed of properly.

We are still performing urgent surgery. I did an emergent glaucoma procedure yesterday and took extreme measures. We used the minimum possible staff: the anesthesiologist, one scrub nurse, and one circulating person. Only two other staff were in our center, and we minimized staff-patient contact. The pre- and postoperative periods were done in a predesignated room with the patient’s name on the door. Everybody in the room was wearing an N95 mask, and the patient was wearing a disposable face mask.

We have devised our own flexible plastic drape to further protect the patients and staff during the administration of the peribulbar anesthesia, the procedure, and the immediate post-op care: It enables visualization of the airways, allows the patient to drink and eat, and contains most of the aerosols exhaled. Every member of staff was wearing eye guards to further avoid droplet transmission.

Academics: It is unfortunate that scientific meetings are cancelled or postponed, as they are our “nutrition” for continuing medical education and for sharing our experiences. My practice is exploring more electronic ways of communication, and I think that our field is privileged in that regard.

EyeNet and the Academy website are valuable tools for staying informed—for real-time coverage of COVID-19 in relation to ophthalmology, a great resource is just a click away.

We are entering week No. 7 of our special measures. The situation has certainly improved, and we hope things will get even better soon. As we monitor the ominous spread of this pandemic and continue to work on its management, my heart goes out to the cities and countries that have been stricken the hardest—and to all of you who are involved in the care of these patients. I wish for your safety!

Let us all get through this as soon as possible by employing precautions, patience, and perseverance!

A. John Kanellopoulos, MD

Clinical Professor of Ophthalmology, NYU School of Medicine, New York, NY

Medical Director, The Laservision Clinical and Research Institute, Athens, Greece

Past President: The International Society of Refractive Surgery (ISRS) 2016 and 2017

___________________________

1 aao.org/headline/list-of-urgent-emergent-ophthalmic-procedures. March 27, 2020. Accessed March 31, 2020.

2 Information for healthcare professionals. CDC. www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-nCoV/hcp/index.html. Updated March 26, 2020. Accessed March 31, 2020.

3 Coronavirus disease. ECDC. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en. Accessed March 31, 2020.

4 Guidance for health workers. WHO. www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/technical-guidance/health-workers. Accessed March 31, 2020.

|

More at the Meeting

From research to reimbursement, get up to speed on COVID-19. The program committees for AAO 2020 (Nov. 14-17) and Subspecialty Day (Nov. 13-14) have invited experts from around the world to present the most up-to-the-minute news on COVID-19. And don’t miss the American Academy of Ophthalmic Executives’ program (Nov. 13-17), which will explain how you and your staff can adapt to the “new normal” by making your practice leaner and more resilient.

For more on this year’s annual meeting, see Destination AAO 2020. Stay up to date by bookmarking aao.org/2020.

|