By Nikolas J. S. London, MD, and Emmett T. Cunningham Jr., MD, PHD, MPH

Edited by Thomas A. Oetting, MD

This article is from April 2008 and may contain outdated material.

Sergio Batista* was a hard-working mechanic with a wife and a newborn daughter. One afternoon in the spring of 1995, he noticed some difficulty reading the print on the label of an alternator he was about to install. He tried blinking a few times, but this really didn’t help. Already several cars behind schedule, this was the last thing he needed to worry about, so he didn’t—he pushed on and finished his work. Unfortunately, things only got worse over the next few days. His vision seemed to be getting blurrier, and his eyes became red and painful. He knew it was time to see a doctor.

Initial Diagnosis

Mr. Batista had no significant medical history and had never seen an eye doctor before. He described his symptoms as “about a week of blurriness” that had recently been accompanied by “a little pain” and “redness.” He acknowledged mild photophobia but denied any other visual or systemic symptoms.

On initial examination, Mr. Batista seemed alert and oriented. His best- corrected visual acuity was 20/40 on the right and 20/30 on the left. His intraocular pressure and pupillary responses were normal bilaterally. His slit-lamp examination revealed 3+ bilateral anterior inflammation with large, granulomatous keratic precipitates. There were no iris abnormalities. Dilated ophthalmoscopic examination revealed moderate vitritis, serous retinal detachments, and optic disc edema and hyperemia in each eye. Initial workup included a CXR, RPR, MHA-TP, ANA, ESR, PPD, ACE and lysozyme, all of which were unrevealing.

Despite the presence of moderate vitritis, serous retinal detachment and optic disc swelling, a nonspecific diagnosis of granulomatous uveitis was given, and Mr. Batista was started on hourly topical corticosteroids and a cycloplegic/mydriatic agent. Over the month following presentation, Mr. Batista’s symptoms progressed and he was admitted to the hospital for evaluation of two weeks of blindness, dizziness, leg weakness and nausea.

Diagnosis Reconsidered

Once in the hospital, Mr. Batista’s medical records were reviewed carefully and he was noted to still have bilateral serous retinal detachments. At this point, the diagnosis of Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada (VKH) syndrome was made. After initial treatment with intravenous methylprednisolone, Mr. Batista’s vision and systemic symptoms improved rapidly. He was discharged after several days, and he continued to improve on high-dose oral prednisone.

|

|

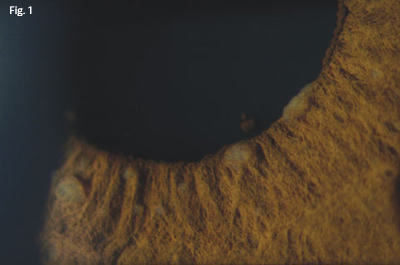

At the Slit Lamp. This photo, taken 10 years after he first reported blurry vision, shows Koeppe nodules at the iris margin and Busacca nodules on the iris surface.

|

A Persistent Disease Course

Over the next 10 years, Mr. Batista experienced frequent recurrences of ocular inflammation with waxing and waning subretinal fluid.

For eight years these recurrences were treated with topical and systemic corticosteroids. Although each episode resolved, his overall visual function gradually declined. In addition, he exhibited clear signs of corticosteroid toxicity, including mood swings, weight gain and ocular hypertension.

In late 2003, he was started on systemic methotrexate, and he has been on various corticosteroid-sparing immunosuppressive agents ever since. These agents have decreased the frequency of his recurrences but have not eliminated them altogether, nor have they prevented complications related to his VKH syndrome.

His corticosteroid-induced ocular hypertension required a trabeculectomy on his left eye in September 2004, and he developed bilateral posterior subcapsular cataracts and underwent a left cataract extraction with IOL implantation in March 2005.

|

|

|

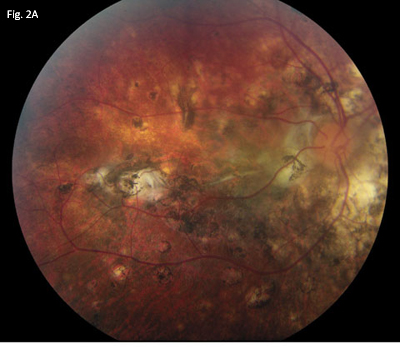

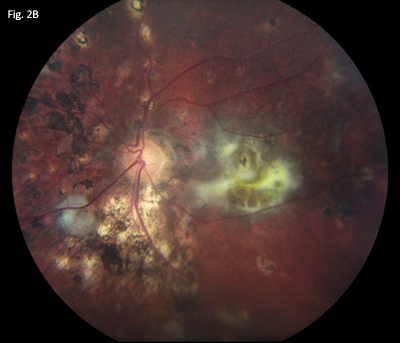

Fundus Findings. Photos of the right (2A) and left (2B) eyes show RPE alterations, loss of choroidal melanocytes and a resultant sunset-glow fundus, choroidal Dalen-Fuchs–like nodules, and subretinal fibrosis bilaterally.

|

We Get a Look

Shortly after his cataract surgery, Mr. Batista presented to our clinic. At this visit he was in the midst of another recurrence while on systemic cyclosporin A and topical corticosteroids.

What we saw. Examination revealed that he had a BCVA of 20/40 on the right and 20/400 on the left.

His IOPs were 16 mmHg on the right and 15 mmHg on the left.

Gonioscopy revealed open angles for 360 degrees with scattered peripheral anterior synechiae and pigment bilaterally. A shallow bleb was present superiorly. There was moderate anterior chamber cell with trace flare, scattered iris nodules (Fig. 1) and broad posterior synechiae bilaterally. A well-centered posterior chamber IOL was present on the left, whereas examination on the right showed moderate nuclear sclerotic and posterior subcapsular cataract.

The ophthalmoscope revealed rare vitreous cell, a cup-to-disc ratio of 0.3, extensive alterations of retinal pigment epithelium, widespread loss of choroidal melanocytes producing a sunset-glow fundus, and scattered choroidal Dalen-Fuchs–like nodules bilaterally. Several areas of subretinal fibrosis were noted (Figs. 2A and 2B), including a large area of subfoveal fibrosis on the left.

Fluorescein angiography showed no evidence of active posterior segment inflammation.

We make a management decision. Clinically, our patient had a 10-year history of recurrent VKH syndrome complicated by glaucoma, cataract formation and subretinal fibrosis when he presented to us with active anterior segment inflammation. As per prior reports, Mr. Batista denied any history of poliosis, vitiligo or alopecia.

We restarted Mr. Batista on 40 mg prednisone with a slow taper, while continuing his cyclosporin A, and he responded well with resolution of his anterior segment inflammation.

On his most recent visit, his BCVA was 20/30 on the right and 20/200 on the left.

Discussion

It is a multisystem disorder. VKH syndrome is characterized by bilateral granulomatous panuveitis associated with serous retinal detachments, optic disc edema, neurologic abnormalities and skin pigmentary changes.

Systemic manifestations may include tinnitus, vitiligo, alopecia, headache and meningismus.

VKH syndrome is thought to be produced by a T cell–mediated autoimmune process directed against melanocyte antigens.

Its incidence varies. The syndrome has a higher prevalence in Asians, Latinos and American Indians, and is slightly more common in women than in men. VKH syndrome may occur at any age but is particularly common in the fourth to sixth decades of life.

It has four phases. Classically, VKH syndrome is described as having four phases: prodromal, acute uveitic, convalescent and chronic recurrent. Classic findings in the chronic recurrent phase include RPE alterations, widespread loss of choroidal melanocytes producing a sunset-glow fundus and choroidal Dalen-Fuchs-like nodules which were all present in our patient as well as cutaneous vitiligo, poliosis and alopecia.

Complications may imperil vision. The chronic, recurrent phase of VKH disease is often accompanied by vision-threatening complications, including cataract, glaucoma, choroidal neovascular membranes, subretinal fibrosis, epiretinal membrane formation and macular atrophy.1 and [i] These complications are common, with at least one occurring in 42 percent of eyes.[ii] Cataract is the most common complication, occurring in 30 to 42 percent of eyes,2, 3 and [i, ii, iii] followed by glaucoma in 18 to 45 percent of eyes,2, 3 and [i, ii, iv] choroidal neovascular membrane formation in 5 to 11 percent of eyes,3 and [ii, v] and subretinal fibrosis in 5 to 8 percent of eyes.[i, vi]

Certain findings on initial presentation, such as poor visual acuity (< 20/200), the presence of severe anterior chamber inflammation[ii] with or without posterior synechiae,2 and [i] and Latino ethnicity,[vi] may portend an increased risk of future complications, including more frequent recurrences and poor long-term visual outcome.

The importance of prompt, aggressive therapy for VKH syndrome. Current guidelines urge prompt initiation of high-dose systemic corticosteroid therapy (1 to 1.5 mg/kg/day) concurrent with a corticosteroid-sparing immunosuppressive agent, with the goal of tapering patients off corticosteroids within two to three months.4 Rapid and aggressive treatment is important to minimize disease duration, lessen the risk of progression into a chronic recurrent form of disease, and reduce the incidence of systemic and ocular complications.2, 3, 5, 6

Treatment with systemic corticoste-roids reduces the risk of loss of visual acuity to 20/200 or worse in the better seeing eye by 67 percent and reduces the risk of choroidal neovascularization or subretinal fibrosis by 82 percent.1 Similarly, the use of immunosuppressive drug therapy has been associated with a 67 percent risk reduction for vision loss to 20/50 or worse and a 92 percent risk reduction for vision loss to 20/200 or worse in better-seeing eyes.1

Mr. Batista’s Progress

Our patient had a disease course that was particularly difficult to control. The number and severity of the complications in this case was probably due to a number of factors, including the patient’s ethnicity, the severity of the inflammation at presentation, and the initial delay in use of systemic corticosteroids and corticosteroid-sparing immunosuppressive agents.

___________________________

* Patient’s name is fictitious.

___________________________

1 Bykhovskaya, I. et al. Am J Ophthalmol 2005;140:674–678.

2 Ohno, S. et al. Jpn J Ophthalmol 1988;32:334–343.

3 Rubsamen, P. E. et al. Arch Ophthalmol 1991;109:6.

4 Damico, F. M. et al. Semin Ophthalmol 2005;20:183–190.

5 Moorthy, R. S. et al. Surv Ophthalmol 1995;39:265–292.

6 Ohno, S. et al.Am J Ophthalmol 1977;83:735–740.

Due to space limitations, the following references were not included in the print version of this article:

[i] Read, R. W. et al. Am J Ophthalmol 2001;131:599–606

[ii] Al-Kharashi, A. S. et al. Int Ophthalmol 2007;27:201–210

[iii] Moorthy, R. S. Am J Ophthalmol 1994;118:197–204

[iv] Forster, D. J. et al. Ophthalmology 1993;100:613–618

[v] Moorthy, R. S. et al. Am J Ophthalmol 1993;116:164–170

[vi] Kuo, I. C. et al. Ophthalmology 2000;107:1721–1728

___________________________

Dr. London is a second-year resident at California Pacific Medical Center in San Francisco. Dr. Cunningham is currently director of the uveitis service at CPMC and an adjunct clinical professor of ophthalmology at Stanford University.

___________________________

This submission was supported in part by The San Francisco Retina Foundation and The Pacific Vision Foundation.