By Timothy S. Wells, MD, and C. Annie Chang, BS

Edited by Sharon Fekrat, MD, and Ingrid U. Scott, MD, MPH

This article is from June 2012 and may contain outdated material.

Giant fornix syndrome, an uncommon condition that results in recalcitrant conjunctivitis in elderly patients, was first described by Rose in 2004.¹ Greater awareness of this syndrome is important for ophthalmologists, especially when they have excluded other diagnostic possibilities.

Pathophysiology

Giant fornix syndrome is a chronic staphylococcal pseudomembranous conjunctivitis that arises from a self-perpetuating infection of a nidus of protein coagulum located in the expansive upper conjunctival fornices of the elderly (Figs. 1-3).

Patients present with recurrent bouts of purulent ocular discharge and conjunctivitis that is refractory to medical treatment. Some may develop secondary scarring and vascularization of the cornea. All have large superior conjunctival fornices that are thought to develop from age-related disinsertion of the levator muscle aponeurosis, which tugs on the conjunctiva instead of the tarsus, thereby increasing the depth of the fornix.

Mechanism. The disease process appears to begin with an initial mild conjunctivitis that may cause protein exudation from inflamed tarsal conjunctiva. The bacteria-covered proteins are then sequestered in the deep superior fornix, resulting in bacterial overgrowth. The bacterial proliferation leads to further release of protein from the chronically inflamed conjunctiva. Eventually, the chronic protein exudation may form a pseudomembrane.

The condition can be exacerbated by lacrimal duct obstruction, which may increase the bacterial load in the tear lake. In such a toxic environment, the corneal surface may develop irreversible vascularization, scarring, and even spontaneous perforation.

Pathogens. The predominant pathogen seems to be Staphylococcus aureus, and the failure to improve symptoms with low-dose topical antibiotics suggests sequestration of bacteria within the forniceal coagulum.S. aureus was isolated from conjunctival swabs in all 12 patients examined by Rose, but a small growth ofPseudomonas aeruginosa was also isolated in one case.¹

|

|

Chronic Inflammation. (1) In this case of bilateral giant fornix syndrome, widespread severe tarsal conjunctivitis is associated with bilateral ptosis. The muted corneal light reflexes are due to toxic keratopathy. (2) Marked reduction of ocular inflammation is noted following eight days of intensive therapy. (3) As seen here, affected patients typically show an unusually deep upper fornix, often 2 to 3 cm.

|

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is made with a good history and an examination that includes inspection of the superior fornix.

Primary clues. Affected patients typically have a history of prolonged conjunctivitis that recurs despite medical therapy or successful lacrimal drainage surgery. Unilateral symptoms seem to be more common than bilateral symptoms on presentation.¹ On exam, the presence of prominent superior fornices can be an initial clue, while evidence of toxic keratopathy, purulent ocular discharge, and large protein deposits visualized in the superior fornix are strong indicators.

Double eversion technique. The diagnosis requires careful inspection of the superior fornix, which can be aided by double eversion of the upper eyelids using a Desmarres retractor. It is helpful to apply topical anesthetic (proparacaine, 0.5 percent solution) to the eye before the procedure is performed. The patient is instructed to look straight ahead or, preferably, down when the superior fornix is inspected. The full extent of the superior fornix can be visualized and swept with a cotton-tipped applicator that has been soaked with topical anesthetic (lidocaine, 4 percent solution). The technique is typically well tolerated.

If a Desmarres retractor is not available, a bent paper clip can be used to assist with the procedure.²

|

|

|

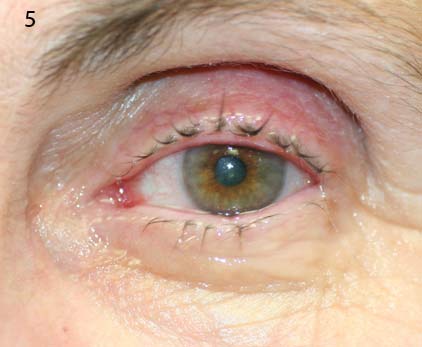

SURPRISE. (Fig. 4) A suspected case of giant fornix syndrome turned out to be a retained soft contact lens. (Fig. 5) One week after the lens was removed, the patient had complete resolution of her discharge and left-sided ptosis.

___________________________

A 70-year-old retired nurse was referred to the Medical College of Wisconsin for evaluation of persistent conjunctivitis in her left eye that had recurred over the previous 18 years.

Despite an extensive history of treatment, she continued to experience purulent morning discharge, dry eye, redness, and excessive tearing. On examination, her visual acuity was 20/20 in each eye, and there was left upper eyelid ptosis associated with conjunctival inflammation. There was no evidence of nasolacrimal duct obstruction or canaliculitis. The depth of her superior sulcus prompted suspicion of possible giant fornix syndrome.

Double eversion of her upper left eyelid led to the discovery of an old soft contact lens resting in the superior fornix (4). The contact lens was easily swept free. Three years later, the patient reports that she is doing well and rarely uses any artificial tears (5).

|

Differential Diagnosis

Conjunctivitis that is chronic, recurrent, and unilateral can be linked to myriad causes. In this instance, the differential is limited because the discharge is mucopurulent. The typical culprits behind chronic watery conjunctivitis—such as viruses and allergic antigens—are excluded.

Keratitis and conjunctivitis. Bacterial conjunctivitis often causes purulent discharge, but it typically has an acute course. However, a prolonged course of purulent conjunctivitis may occur if the lids or lacrimal apparatus are infected with staphylococcal or pneumococcal bacteria.

Keratopathy linked to irritation or exposure of the corneal surface may cause chronic mucopurulent conjunctivitis. Precipitating factors include direct irritants, eyelid abnormalities, facial paralysis, and exophthalmos. Molluscum contagiosum is another cause of keratitis and conjunctivitis, but the pathogen is a poxvirus that produces a watery, not purulent, discharge. Moreover, molluscum papules with central umbilication typically are visible along the eyelid margins.

A masquerading malignancy or vascular disorders such as a dural arteriovenous fistula may cause chemosis, proptosis, and unilateral conjunctivitis. However, a thorough history and exam can assist in differentiation.

Lacrimal drainage system disorders. Nasolacrimal duct obstruction, chronic blepharitis, and canaliculitis may lead to excessive discharge and can be ruled out by clinical examination. This should include evaluation of lid margins, inspection for a pouting punctum with pericanalicular inflammation, lacrimal sac compression for reflux, canalicular probing and irrigation with attention to lacrimal sac distention and reflux, dye disappearance, and Jones tests. Canaliculitis may be difficult to recognize, even by astute clinicians, and there may be a delay of several months before it is diagnosed.³

In cases where the etiology remains unclear in a patient with a deep superior sulcus, giant fornix syndrome should be considered and the superior fornix should be carefully inspected.

Treatment

Recommended treatment includes hourly administration of potent topical steroids (such as prednisolone, 1 percent), given for several weeks. In addition, patients should be given a topical antibiotic (ofloxacin or chloramphenicol) and an appropriate systemic antibiotic (azithromycin, ciprofloxacin, or flucloxacillin). The systemic antibiotic may need to be taken for a period of 10 to 30 days, depending on the persistence of coagulum formation.¹

During the first few days of treatment, regular sweeping of the upper fornix with a cotton swab can assist in clearing the protein coagulum. If conservative treatment fails, surgical management may require superior fornix resection and, in some cases, lacrimal surgery. It should be noted that some of Rose’s patients had persistent discharge despite prior lacrimal surgery.

___________________________

1 Rose GE. Ophthalmology. 2004;111(8):1539-1545.

2 Bode DD, Manson RA. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1978;15(1):54.

3 Freedman JR et al. Surv Ophthalmol. 2011;56(4):336-347.

___________________________

Dr. Wells is assistant professor of ophthalmology and Ms. Chang is a medical student; both are at the Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee. The authors report no related financial interests.