Download PDF

Meiling Chen* is a 59-year-old Taiwanese woman. When she initially sought treatment, she was living in North Carolina. She complained of ocular irritation and redness in her left eye, starting about 4 months earlier. Her local ophthalmologist had prescribed topical and oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and steroids, but her symptoms persisted. Ms. Chen was referred to our glaucoma service for elevated intraocular pressure (IOP) in the setting of a diagnosis of scleritis.

Initial Course

Ms. Chen’s referring ophthalmologistinitially treated her with topical nepafenac 3 times daily followed by oral ibuprofen at 400 to 600 mg 2 or 3 times daily over 2 months. Ms. Chen was then prescribed an oral prednisone regimen tapering from 40 mg daily over 9 days. She did not improve on this treatment and was started on topical brimonidine/timolol twice daily in the left eye for elevated IOP.

Clinical findings. Records from a recent clinic visit with the referring ophthalmologist noted uncorrected visual acuity of 20/25 in each eye. IOP by applanation was 17 mm Hg in the right eye and 24 mm Hg in the left eye. Pupillary reaction, confrontation visual fields, and ocular movements were recorded as normal, and there was no afferent pupillary defect. The ophthalmologist reported dilated scleral vessels that were most pronounced nasally and temporally in the left eye. A normal dilated fundus exam had been documented 2 months earlier.

MRI. The referring ophthalmologist ordered magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the orbits with and without contrast to evaluate for a compressive lesion and reviewed the study with the local radiologist. They confirmed that there were no mass lesions. The MRI was also reported to have ruled out carotid-cavernous fistula and arteriovenous malformation. At this point, the patient was referred to our clinic for a second opinion on the persistent scleritis and for a glaucoma evaluation.

We Get a Look

Ms. Chen was evaluated in our glaucoma clinic 3 weeks after referral. At that time, she was symptomatic, with left eye redness and swelling and was using topical brimonidine/timolol in both eyes twice daily. Our exam showed the following:

- Uncorrected visual acuity was 20/20 in each eye.

- IOP by applanation was 19 mm Hg in the right eye and 34 mm Hg in the left eye.

- Central corneal thickness was 551 μm in both eyes.

- Pupillary reaction, ocular movements, and confrontation visual fields were normal.

- Gonioscopy revealed angles open to scleral spur in both eyes. However, blood was visible in Schlemm’s canal superiorly and inferiorly in the left eye.

- Mild proptosis (2 mm compared to contralateral on Hertel exophthalmometry) and mild eyelid edema were present in the left eye.

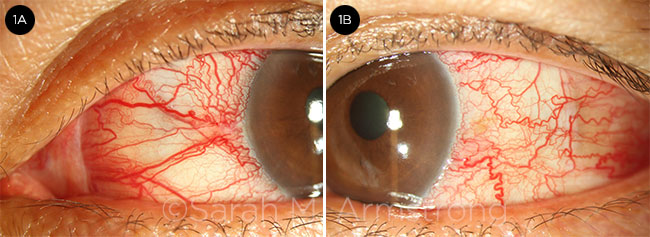

- Moderate hyperemia and tortuous, engorged episcleral vessels were visible in the left eye (Fig. 1).

- Flame hemorrhage was present at the nasal margin of the left optic disc.

- The cup-to-disc ratio was 0.5 in the right eye and 0.45 in the left, with good rim margins.

- Retinal vessels in the left eye were tortuous.

- Intraretinal hemorrhage was seen in the temporal midperiphery of the left eye.

The review of systems was positive for occasional pulsatile tinnitus and negative for prior head trauma. We reviewed the recent orbital MRIs and saw no obvious orbital or intracranial mass lesions. However, we noted asymmetric dilatation of the left superior ophthalmic vein.

|

|

ABNORMAL VESSELS. The patient’s dilated and tortuous conjunctival and episcleral vessels appear atypical for scleritis. (Left eye: 1A, nasal; 1B, temporal.)

|

Differential Diagnosis and Workup

At this point, our working diagnosis was glaucoma secondary to increased episcleral venous pressure in the left eye. However, we were highly suspicious about the possibility of carotid- cavernous fistula despite the normal radiology report on the previous MRI.

Our differential diagnosis also included thyroid eye disease, cavernous sinus thrombosis, and amyloidosis. Although we did not observe an orbital mass on MRI, we included this in the differential as a possible etiology for elevated episcleral venous pressure.

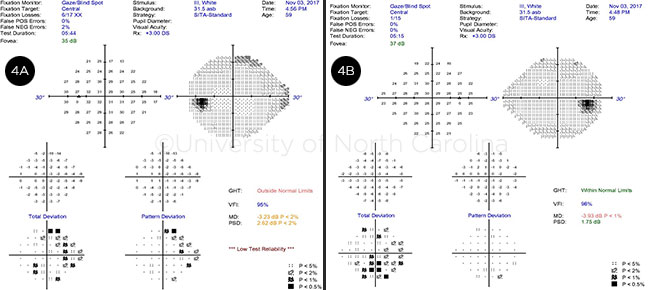

In the clinic. Our clinical evaluation included Humphrey visual field testing, which was full in the right eye and demonstrated a superior nasal step and early inferior nasal step in the left eye (see Web Extra, Fig. 4).

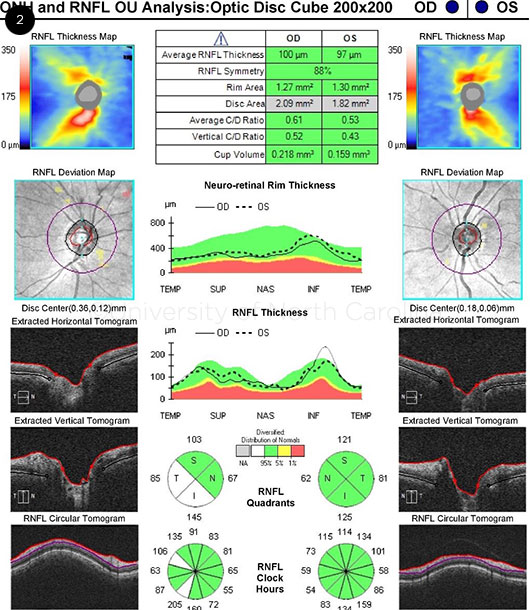

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) of the optic nerve revealed a thickened inferior and temporal nerve fiber layer in the right eye and normal thickness in the left eye (Fig. 2).

We prescribed maximum topical therapy to lower the IOP in the left eye, adding bimatoprost and dorzolamide to her existing brimonidine/timolol regimen.

Lab findings. Laboratory evaluation for thyroid disease revealed a slightly elevated thyroid-stimulating hormone level of 3.4 μIU/mL (upper limit of normal, 3.3 μIU/mL).

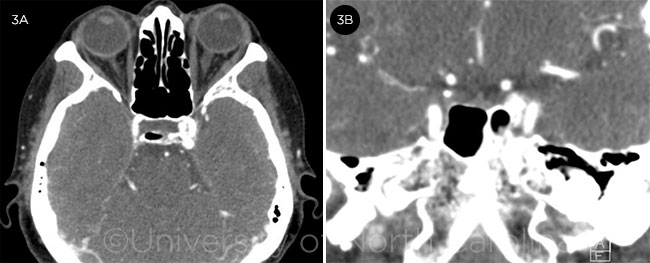

CTA. A computed tomographic arteriogram (CTA) revealed rapid arterial filling of the venous plexus of the left cavernous sinus with engorgement (Fig. 3). A direct communication with the internal carotid arteries was not convincingly demonstrated. The reading radiologist at our institution concluded that the findings were most consistent with a left carotid-cavernous fistula.

|

|

OCT. Retinal nerve fiber thickness, while normal in the affected left eye, is significantly thinner inferiorly compared to the right eye.

|

Next Steps

Ms. Chen returned 2 weeks later for a check of IOP, which was controlled at 18 mm Hg in the left eye. We discussed the laboratory and CTA results with her and recommended CT carotid angiography to confirm the diagnosis.

A carotid angiogram was scheduled a few weeks later. While in the angiogram suite, Ms. Chen developed significant anxiety and was unable to proceed with the testing. She decided to return to Taiwan for further care.

|

|

CTA. (3A) Axial and (3B) coronal CTA slices reveal asymmetric filling of the left cavernous sinus.

|

Our Diagnosis

Although we were unable to complete the confirmatory testing, Ms. Chen’s signs and symptoms were strongly suggestive of carotid-cavernous fistula. They included a distinctive clinical appearance of tortuous and engorged episcleral vessels, proptosis, and retinal hemorrhages, along with CTA findings of rapid filling and engorgement of the cavernous sinus.

Discussion

Abnormal communication between the cavernous sinus and the internal carotid artery or its branches can lead to direct or indirect dural-type fistulas, respectively.1 Ophthalmic manifestations are well documented in the literature and include eye redness, chemosis, proptosis, increased IOP, stasis retinopathy, choroidal effusion, optic neuropathy, and cranial nerve palsy.1

The initial signs and symptoms of carotid-cavernous fistula can be mistaken for more common causes of red eye, resulting in misdiagnosis of this potentially blinding and life-threatening entity.2 See “Clinical Pearls for Diagnosis” for further pointers to help identify carotid-cavernous fistula.

Direct high-flow fistulas typically cause acute manifestations compared to indirect low-flow fistulas, which have a more indolent clinical course.1

|

|

VISUAL FIELDS. (4A) Left eye demonstrates a nasal step that is greater superiorly than inferiorly. (4B) Right eye field appears full.

|

Imaging

The gold standard for diagnosing carotid-cavernous fistula is digital subtraction angiography (DSA), an interventional radiology technique that subtracts precontrast images from subsequent contrasted images.1 This technique is also useful in guiding subsequent treatment, if warranted.

CTA has been shown to have diagnostic sensitivity similar to DSA.1 Magnetic resonance angiography has significantly lower sensitivity compared with CTA and DSA.1 MRI and CT are usually insufficient to make or exclude the diagnosis of carotid-cavernous fistula.1

Treatment

Some indirect fistulas may be observed, while others require intervention.1 Noninvasive techniques include manual digital compression of the ipsilateral internal carotid artery at the neck or the superior ophthalmic vein at the superomedial orbital rim.1

Stereotactic radiosurgery and endovascular intervention are additional options.1 Modern techniques for closing direct fistulas include endovascular embolization with materials such as coils, glue, platinum, polymers, and detachable balloons.1 It is important to make the appropriate referral and/or manage the patient with a team of specialists experienced with such procedures.

Take-Home Points

- Carotid-cavernous fistula should be included in the differential for atypical red eye.

- The arterialized conjunctival and episcleral vessels in carotid-cavernous fistula have a unique appearance that can differentiate it from other causes of red eye.

- A careful history and examination including gonioscopy are crucial for avoiding misdiagnosis.

- CTA or DSA is the best imaging modality for confirming the diagnosis.

- A patient with carotid-cavernous fistula should be managed with a multidisciplinary team of experts.

___________________________

*Patient name is fictitious.

___________________________

1 Henderson AD, Miller NR. Eye (Lond). 2018;32(2):164-172.

2 Ling JD et al. Can J Ophthalmol. 2013:48(1):3-7.

___________________________

Dr. Go is a third-year ophthalmology resident and co-chief resident, and Dr. Fleischman is assistant professor of ophthalmology and glaucoma specialist; both are at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill, N.C. Financial disclosures: None.

Clinical Pearls for Diagnosis

The following tips can help differentiate carotid-cavernous fistula from masquerading conditions.

- Inquire about a history of connective tissue disease, prior head trauma, or past neurosurgical intervention, all of which may contribute to development of a carotid-cavernous fistula.

- Obtain a thorough neurologic review of systems, as patients may not volunteer symptoms such as pulsatile tinnitus.

- Observe the patient’s conjunctival and episcleral vessels, which are generally distinctive in carotid-cavernous fistula. For example, in our patient, the arterialized vessels demonstrated a corkscrew appearance, extended all the way to the limbus, and were separated by relatively white conjunctiva (see Fig. 1).

- Be alert for the pulsation amplitude of the mires when performing applanation tonometry; the amplitude may be greater in an eye with carotid-cavernous fistula.

- Perform gonioscopy to evaluate for blood in Schlemm’s canal or angle closure from uveal congestion.

- Consider performing Hertel exophthalmometry to identify mild proptosis.

In addition, some patients may exhibit venous stasis retinopathy, choroidal effusion, or ischemic or glaucomatous optic neuropathy. Patients with any of these conditions should undergo a careful dilated fundus examination.

|