By Brett D. Gerwin, MD, and Devron H. Char, MD

Edited by Thomas A. Oetting, MD

This article is from January 2010 and may contain outdated material.

Keith Gunderson* is a 42-year-old Caucasian who recently returned from the Middle East, where he had been serving in the U.S. Army. He initially presented to a hospital emergency room with a complaint of ocular irritation. His past medical history was notable for hypertension, hyperlipidemia and depression. At the time of presentation, he was taking amlodipine besylate and benazepril for his hypertension, and atorvastatin for his hyperlipidema. The review of systems was unremarkable. He was treated with topical antibiotics for a supposed corneal abrasion but soon returned with progressive proptosis on the right side.

He Returns to the ER

On his second visit to the ER, he was given oral antibiotics for cellulitis and discharged. After continued deterioration, he returned to the emergency department a third time. An orbital CT scan showed soft-tissue edema without abscess formation. He was admitted for intravenous antibiotic therapy for presumed orbital cellulitis. An MRI of the orbit showed extensive inflammatory change. Marginal improvement was noted after six days of intravenous antibiotics. He remained afebrile with a normal white blood cell count, and was discharged with a plan for five days of outpatient intravenous antibiotics, followed by one to two weeks of oral antibiotics. However, his proptosis, chemosis and ocular motility got worse. This prompted his referral to our clinic.

We Get a Look

We saw the patient nine days after his hospital discharge. On our exam, his acuity was 20/200 in the right eye and 20/25 in the left. There was no relative afferent pupillary defect, and color vision was normal and symmetric. Hertel exophthalmometry showed measurements of 25 mm in the right eye and 20 mm in the left. Motility on the right showed 0 percent elevation, 10 percent adduction, 20 percent abduction and 50 percent depression. Motility on the left was normal. IOP was normal in both eyes. The anterior segment exam showed right periocular edema and severe inferior chemosis (Fig. 1). There was no intraocular inflammation. The right fundus was unremarkable. The left eye was normal.

The patient underwent additional MRI of both orbits, which identified extensive infiltration of the anterior, medial and superior orbit enveloping the rectus muscles, with both intra- and extraconal components (Fig. 2). He was admitted to the hospital and worked up for both infectious and noninfectious inflammatory diseases.

|

|

|

We Get a Look. (Figs. 1 and 2) At the emergency department Mr. Gunderson was initially treated for a supposed corneal abrasion of the right eye. By the time he was referred to us, he exhibited periocular edema and severe inferior chemosis. MRI revealed extensive infiltration of the anterior, medial and superior orbit, with both intra- and extraconal components.

|

Lab Results

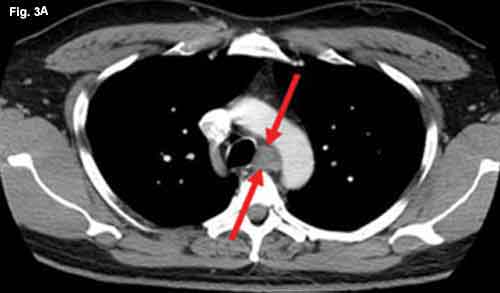

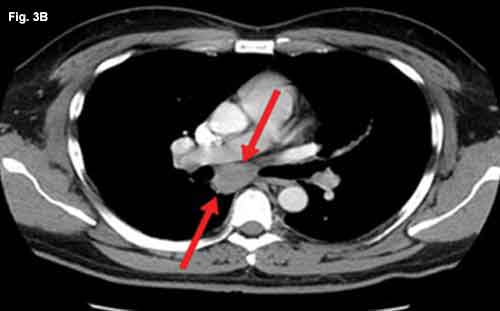

Laboratory evaluation showed normal cell counts and serum chemistries. Liver transaminases were elevated, with an aspartate transaminase (AST) of 62 and alanine transaminase (ALT) of 165. Tests for syphilis, Lyme disease, leishmaniasis, HIV and hepatitis infection were normal. The purified protein derivative (PPD) was normal, as were the lab values for erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) and antineutrophilic cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA). Operative tissue biopsy from the medial orbit was then performed, and tissue was sent for Gomori methenamine silver, acid-fast and Gram stains, as well as culture and histology. Microscopic diagnosis showed noncaseating granulomatous inflammation with multinucleated giant cells and no infectious organisms were identified. CT of the chest showed enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes (Figs. 3A and 3B).

|

|

|

CT Scan. (Figs. 3A and 3B) When we reviewed the CT scan of Mr. Gunderson’s chest, we noted enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes.

|

Diagnosis and Treatment

We made a diagnosis of orbital sarcoidosis. We discontinued his antibiotics and started him on high-dose cortico-steroids (100 mg of prednisone per day).

Follow-up exam three weeks later showed marked improvement with near resolution of periocular edema and chemosis (Fig. 4). Acuity was now 20/40 in the right eye and motility had improved in all fields of gaze.

|

|

Follow-Up. (Fig. 4) The patient was much improved at the three-week follow-up.

|

Discussion

Sarcoidosis is an inflammatory disease of unknown origin affecting multiple organ systems. Within the United States, the annual incidence is 35.5/100,000 for African-Americans and 10.9/100,000 for whites. It is more common in women and in those of either African-American or Northern European descent. Approximately two-thirds of patients are younger than 40 years old at the time of diagnosis.

Symptoms. Sarcoidosis may have a variety of presentations, with 30 to 50 percent of patients being asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis. Constitutional symptoms such as fever and night sweats may occur in 20 to 30 percent of patients while fatigue and muscle weakness occur in up to 70 percent. Findings vary by geographic location, but the lungs, eyes and skin are the most common sites affected, respectively.1Pulmonary symptoms, such as cough and dyspnea, occur in approximately 30 percent of patients. Other presenting findings may include peripheral lymph node enlargement and skin lesions. Cutaneous manifestations of sarcoidosis can include erythema nodosum and lupus pernio, which consists of a plaque—red to purple in color—on the nose, ears, forehead, fingers and toes. Sarcoidosis commonly involves the liver, resulting in abnormal liver function tests (LFTs), as in our patient. Other organs, including the heart, may be affected as well.

Diagnostic tests. Initial testing for sarcoidosis may include blood cell counts, serum chemistries (including calcium levels), ACE levels, chest x-ray, urinalysis and a tuberculin skin test. Other testing may include lysozyme tests, pulmonary function tests, body gallium or PET scans, abdominal imaging, chest CT scan, bronchoalveolar lavage, cardiac MRI, EKG and echocardiography. Tissue biopsy of affected areas with histologic examination is the gold standard for diagnosis.

Two recent case series. Uveitis is its most common ocular manifestation, but sarcoidosis may affect orbital and adnexal structures as well. A recent review of 20 orbital sarcoid cases found a mean age of 50 years. The disease was chronic (months) in 11 patients and subacute (weeks) in nine patients. The presenting symptoms (in order of frequency) were a palpable mass, eyelid swelling, ptosis, globe displacement, proptosis, redness, pain and vision loss. CT scans showed lacrimal gland infiltration in 11 patients (55 percent), orbital mass in four patients (20 percent), optic nerve sheath and dural involvement in four patients (20 percent) and extraocular muscle involvement in one patient (5 percent). The superolateral orbit was most commonly affected (55 percent), followed by superomedial orbit (20 percent). All patients who underwent biopsy showed noncaseating granulomas on histology. Orbital disease was the initial presentation in 19 patients (90 percent), with systemic findings found afterward in 10 patients (50 percent). Ten patients underwent ACE analysis, and two (20 percent) of them showed elevated levels of the enzyme. Treatment involved systemic corticosteroids in most patients, although some were treated with regional steroid injections or other immunosuppressants with good response.2

Another review of orbital sarcoid-osis included 26 patients, of whom 16 (62 percent) were white, seven (27 percent) were African-American, two (8 percent) were Indian and one (4 percent) was Japanese. Their mean age was 52 years. At the initial examination, the most common signs and symptoms were mass/swelling in 23 patients (88.5 percent), proptosis in 11 patients (42.3 percent) and discomfort in eight patients (30 percent). The lacrimal gland was involved in 11 patients (42 percent), and orbital involvement—either diffuse or discrete—was present in 10 patients (38.5 percent). Biopsies on all patients showed granulomatous inflammation without caseating necrosis. Hilar lymphadenopathy was visible on chest x-ray in 17 patients (65 percent). In this study, ACE levels were elevated in 15 patients (62.5 percent). Patients were treated with either oral prednisone, intraorbital steroid injection, surgical debulking or methotrexate, with treatment duration ranging from two to 36 months depending on the response.3

Conclusion

Ophthalmic involvement with sarcoid-osis is relatively common, with uveitis being the most common presentation. Acute onset of extralacrimal orbital inflammation is an uncommon but established presentation of the disease and should be considered as part of the differential diagnosis when there is atypical orbital inflammation.

Our patient presented with isolated orbital involvement, a normal ACE level (though on an ACE inhibitor) and hilar lymphadenopathy along with histology consistent with sarcoid.

Given his history of travel, it was important to evaluate for infectious etiologies such as leishmaniasis and particularly tuberculosis before starting corticosteroids. Patients with evidence of systemic involvement should also be comanaged with an internist or pulmonologist.

___________________________

* Patient name is fictitious.

___________________________

1 Sharma, O. P. Clin Chest Med 29;2008:357–363.

2 Mavrikakis, I. and J. Rootman. Am J Ophthalmol 2007;144:769–775.

3 Prabhakaran, V. et al. Arch Ophthalmol 2007;125:1657–1662.

___________________________

Dr. Gerwin is a retina specialist and oncology fellow with the Tumori Foundation at California Pacific Medical Center in San Francisco.

Dr. Char is director of the Tumori Foundation and clinical professor of ophthalmology at Stanford University.