By Jonathan M. Skarie, MD, PhD, Cynthia G. Pan, MD, Annette D. Segura, MD, and Bhavna P. Sheth, MD

Edited by Thomas A. Oetting, MD

This article is from July 2012 and may contain outdated material.

According to the staff at the urgent care facility, Mary Shannon* had nothing more exotic than conjunctivitis. They gave the 13-year-old some antibiotic drops and sent her home. However, the drops did not relieve her symptoms, and her mother brought her to us four days later with bilateral red, painful eyes and photophobia.

Mary’s mother told us that the girl’s ocular discomfort began suddenly in her right eye and by the next day had spread to involve her left eye, which prompted the trip to the urgent care providers.

In addition, she reported that Mary hadn’t been feeling well for some time. The previously healthy girl had been experiencing severe fatigue for six weeks, to the point where she could no longer participate in sports and was falling behind in her schoolwork. Mary’s fatigue was accompanied by frequent low-grade fevers, diffuse myalgias, and arthralgias. As a result, her pediatrician had initiated an extensive workup, resulting in a referral to a nephrologist for newly diagnosed acute renal insufficiency.

We Get a Look

When we examined her, Mary had readily apparent photophobia but normal visual acuity, color vision, and stereopsis in both eyes. Her pupils reacted normally to light and there was no relative afferent pupillary defect, and her intraocular pressures were within normal limits.

The slit-lamp examination revealed that she had conjunctival injection without chemosis (left greater than right). Both corneas showed 1 to 2+ inferior stellate keratic precipitates but were otherwise normal. There were 2+ cells and mild flare in both eyes (with the left slightly worse than the right). No posterior synechiae were observed. The remainder of the exam, including a dilated fundus exam, was normal.

The Next Step

Mary clearly had acute-onset, bilateral anterior uveitis, and we immediately started her on topical steroids and cycloplegic agents. However, the underlying cause for her uveitis was not as apparent.

As part of the initial workup, Mary’s pediatrician had ordered a number of laboratory tests (complete blood count, electrolyte, thyroid, monospot, rapid strep, Lyme antibody, cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, antinuclear antibody, C3 and C4 complement, and antistreptococcal antibody). The results for these tests were within normal limits. However, we noted that her serum creatinine was elevated at 1.28 mg/dL. In addition, a kidney ultrasound that had been ordered at that time revealed abnormal renal function.

Concurrent with our uveitis diagnosis, a renal biopsy was performed; it revealed tubulointerstitial nephritis (TIN). An extensive workup was performed in collaboration with rheumatology consultants. This ruled out the most probable suspects for our patient’s uveitis: sarcoidosis, ANCA-associated vasculitis, Sjögren syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus, and tuberculosis.

A Rare Entity

Mary was diagnosed with tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis syndrome (TINU), which is found in a subset of patients with TIN.

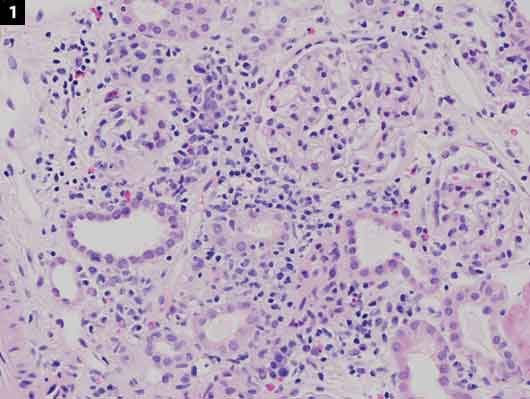

Signs and symptoms. Symptoms of acute TIN are vague and may include fever, malaise, fatigue, and flank pain. The only way to definitively diagnose TIN is with a renal biopsy (Fig. 1).

The uveitis in TINU can precede, accompany, or follow the onset of TIN. In a review of 133 patients with TINU, the onset of uveitis symptoms followed those of nephritis by up to 14 months in 65 percent of cases.1In most instances, the uveitis in TINU is bilateral, acute in onset, and nongranulomatous, and affects only the anterior segment.1 However, there have been case reports of granulomatous inflammation as well as posterior uveitis and panuveitis.1,2

Population. TINU has a median age of onset of about 15 years old, with patients ranging in age from 9 to 74 years.1,2 The syndrome affects both sexes, with an overall predominance of females but a trend toward male predominance in younger age groups.2 There is no association with any geographical regions or particular racial or ethnic groups.1,2

Incidence. TINU has classically been thought of as a rare form of uveitis. However, recent analysis of the literature suggests it may account for as many as 30 percent of cases of acute-onset, bilateral anterior uveitis in young people; and it has been suggested that at least a portion of “idiopathic” cases of uveitis may be due to TINU.2 The vague symptoms of TIN along with the variable timing of ophthalmic symptoms may allow the underlying pathology to go undiagnosed in many cases.

Pathogenesis. TIN is thought to be an immune-related process that can be provoked by an infection or a reaction to a medication; it also can be idiopathic in nature. Common drugs associated with TIN include antibiotics and NSAIDs; however, there is no direct evidence linking these or any other medications to TINU.

The underlying pathogenesis of TINU is unknown, but it is thought to be immune mediated. In a study published last year, researchers found a higher incidence of the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) haplotype HLA-DRB1*0102 in patients with acute-onset, bilateral anterior uveitis, as seen in the TINU population.3

Treatment and prognosis. Standard treatment for anterior uveitis with topical steroids is usually effective, and long-term complications are rare. However, uveitis commonly recurs in patients with TINU.1,2 Most recurrences take place within the first few months after stopping therapy, but some have occurred as much as two years later.1 Given these findings, long-term follow-up is recommended.2

Renal outcomes also are generally good, with the nephritis often spontaneously resolving and rarely recurring. However, there have been cases of chronic renal failure following TINU.2 If kidney functions do not quickly normalize, a short course of high-dose IV or oral steroids is often used.

|

|

What’s Your Diagnosis? (1) A kidney biopsy found that the interstitium was expanded with a mixed infiltrate of lymphocytes, aggregates of plasma cells, and scattered eosinophils. Two unremarkable glomeruli were evident.

|

Patient Update

Mary’s uveitis responded well to treatment with a topical steroid and cycloplegic. However, her serum creatinine level increased to 1.89 mg/dL and stayed persistently elevated, so she was treated with three doses of IV methylprednisolone followed by oral prednisone.

When we saw Mary at her follow-up appointment, both her ophthalmic and systemic symptoms had, for the most part, been resolved. She will be followed closely to monitor for any recurrence of her nephritis or uveitis.

___________________________

* Patient name is fictitious.

___________________________

1 Mandeville JT et al. Surv Ophthalmol. 2001;46(3):195-208.

2 Mackensen F, Billing H. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2009;20(6):525-531.

3 Mackensen F et al. Br J Ophthalmol. 2011;95(7):971-975.

___________________________

Dr. Skarie is an ophthalmology resident, Dr. Pan is professor of pediatrics and chief of nephrology, Dr. Segura is assistant professor of pathology, and Dr. Sheth is professor of ophthalmology; all are at the Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee. The authors report no related financial interests.