This article is from January 2012 and may contain outdated material.

Improvements in materials and manufacturing are allowing unprecedented degrees of customization in therapeutic and refractive contact lenses. Here are some recent developments in specialized lenses that Eye M.D.s should know about.

Most ophthalmologists spend more time on medical and surgical therapies for their patients than they do on prescribing and fitting contact lenses. So perhaps it has been easy for busy clinicians to miss some important changes in the contact lens landscape during the first dozen years of the 21st century.

From reliable torics that can give patients crisp vision to new scleral lens designs that can literally change lives, contact lenses are a refractive and therapeutic modality worth watching as 2012 begins.

Why Contact Lenses Matter to Eye M.D.s

Today, many of the experts in day-to-day contact lens fitting come from the ranks of specially trained non-MDs, said Sanjay V. Patel, MD, associate professor of ophthalmology at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

“There are probably a few ophthalmologists who still fit contact lenses personally,” Dr. Patel said. “Ophthalmology in the last decade or two has migrated to concentrating on surgical and medical therapies instead of basic nonsurgical refractive correction. This has created an opportunity for others in the eye care field—optometrists—to fill the gap.” Dr. Patel believes that many patients would benefit from having an ophthalmologist who is familiar with the new capabilities of contact lenses.

Deborah S. Jacobs, MD, medical director of the Boston Foundation for Sight in Needham, Mass., thinks there is an urgent unmet need. “I want ophthalmologists to know about all the new types of contact lenses—scleral lenses, toric models, aspherics and multifocals for presbyopia and so on—that could help their patients,” said Dr. Jacobs, who is also the scientific programs chairwoman of the Contact Lens Association of Ophthalmologists and on the faculty of Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary. “Because if, as ophthalmologists, we aren’t informed about what is available, we will not be fully serving our patients’ eye health and visual needs.”

Avoiding Infections

Not all of the recent contact lens research has focused on innovations in lens material and design. In fact, studies done on contact lens–related infection have an arguably greater impact, as they are also relevant to the much larger group of patients who use standard refractive lenses.

Lessons from keratitis outbreaks. By studying the microbial keratitis outbreaks of 2004 to 2007, health researchers have found some specific steps that contact lens wearers can take to prevent infections. But, given a choice between convenience and 100 percent disinfection, most lens wearers are still choosing convenience.

Sleeping in contact lenses remains the single biggest risk factor for contact lens–related eye infections. Beyond that, researchers have investigated the properties of, and interactions among, disinfecting solutions, user behavior, lens materials, lens cases and microbial life cycles.

Recommendations to reduce risk. Overall, the results support three practical recommendations to give to patients for minimizing infection risk:

- Disinfect daily-wear lenses with a 3 percent hydrogen peroxide system. So far, this is the only six-hour soaking medium that kills 100 percent of encysted Acanthamoeba.1

- Rub contact lens cases daily to prevent biofilm formation. This also applies to antimicrobial, silver-impregnated cases, which inhibit some but not all bacteria.2,3 (Method: Discard used disinfectant; vigorously rub the inside surfaces with a clean finger and disinfectant; rinse; and store case normally.3,4)

- Replace the lens case often, and throw out the old one. Do this at least monthly, preferably more often.

“Hydrogen peroxide disinfecting systems seem to be the safest type, so increasing their use would be a good way to reduce the number of contact lens–related infections,” said Mark Willcox, BSc, PhD, a professor and microbiology researcher at the School of Optometry and Vision Science at the University of South Wales, in Sydney, Australia.

Many solutions have no effect on Acanthamoeba. A 2009 study at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention tested nine commonly used multipurpose solutions for antimicrobial activity and found that all failed to kill any encysted Acanthamoeba during six hours of soaking. That compared with 100 percent effectiveness for one hydrogen peroxide system (Clear Care, Ciba Vision) and 34 percent for another (AMO UltraCare, Abbott Medical Optics).1

Persuading contact lens users to switch from a multipurpose solution to hydrogen peroxide has been a hard sell, though. Use of hydrogen peroxide disinfectant has risen slowly since the 2004 to 2007 microbial keratitis crisis. It reached 11 percent in 2009 and 16 percent in 2011, according to marketing research by A.C. Neilsen Co.5

“Contact lens wearers want the convenience of a multipurpose solution,” Dr. Willcox said. “Also, some people don’t like to use hydrogen peroxide because occasionally they forget to neutralize it before putting the lenses into their eyes, and it stings terribly.”

___________________________

1 Johnston SP et al. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47(7):2040-2045.

2 Wu YT et al. Optom Vis Sci. 2011;88(10):E1180-1187.

3 Amos CF, George MD. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2006;29(5):247-255.

4 Szczotka-Flynn LB et al. Cornea. 2009;28(8):918-926.

5 Nichols JJ. Contact Lens Spectrum (annual report). Jan. 2011.

___________________________

Dr. Willcox has received compensation for travel, speaking and research studies from Alcon, Allergan, AMO, Bausch + Lomb and Ciba-Vision.

|

Scleral and Hybrid Lenses

Large-diameter, rigid contact lenses, which are supported by the sclera rather than the cornea, have been one of the most active areas for contact lens innovation over the last five years.

Advances in materials allow larger lenses. Although scleral lenses have a long history, concern about hypoxic damage from blanketing the anterior surface of the eye with PMMA formerly kept scleral lenses from entering the market in a big way. But the availability of newer rigid gas-permeable (RGP) materials with high oxygen transmissibility (high Dk) has changed the picture.

Peter R. Kastl, MD, PhD, professor of ophthalmology at Tulane University in New Orleans, explained that the addition of silicone to the lens material blend made the difference. “Silicone moves the polymer chains apart, creating pores, as it were, that allow the oxygen directly through. And over the last 20 years, we’ve seen a progression of higher and higher oxygen transmission in RGPs. This has allowed the development of larger lenses of 15 mm and more.”

With diameters of up to 24 mm, these high-Dk lenses have edges that can extend out to the scleral periphery, nearly all the way to the insertion of the extraocular muscles. If the lens crosses the limbus, a transitional zone between the optic and the lens periphery is elevated to prevent lens pressure from damaging the limbal stem cells.

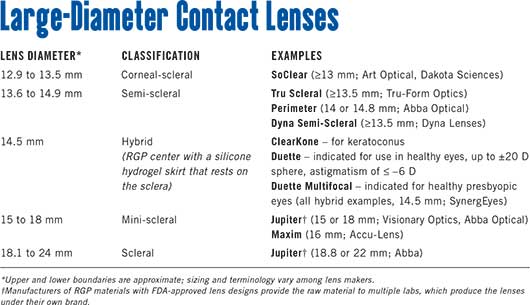

Variations on the scleral theme. Modified, smaller RGP lenses, which are not true scleral lenses, are separated by size into mini-scleral, semi-scleral or corneal-scleral types (see “Large-Diameter Contact Lenses” for examples). Their edges are seated, respectively, just outside the limbus, just inside it, or partly on the cornea and partly on the sclera.

No corneal touch. Apart from their large size, the most distinctive feature of scleral lenses and variants is their markedly conical shape, designed not to touch the cornea. The optical zone vaults 10 to 150 µm over the patient’s damaged, sensitive or irregular cornea, creating a reservoir that the wearer fills with sterile saline before insertion.

The Many Uses of Scleral Lenses

Researchers have reported success using custom-fitted sclerals for a wide range of ocular problems, including chronic graft-versus-host disease, pellucid marginal degeneration, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, ocular cicatricial pemphigoid, keratoconus, irregular astigmatism after penetrating keratoplasty, post-LASIK ectasia and nonhealing epithelial defects. Findings from these reports1-6 on scleral lenses indicate that:

- They were stable on the eye and well tolerated.

- Patients experienced less pain, photophobia and other symptoms of severe dry eye.

- Patients’ visual acuity typically was better than their previous best spectacle-corrected or contact lens–corrected visual acuity.

- The refractive effect of the fluid in the reservoir corrects blurring from surface irregularities.

When to try sclerals. Dr. Kastl said that “when all else fails, try a scleral lens.” Such lenses provide the opportunity to, figuratively, “resurface the road for really bad corneas” and overcome some of the visual problems associated with an irregular corneal surface and tear film. “You essentially take the cornea out of the refractive equation,” he said.

Dr. Kastl has a number of patients who had Intacs implanted for keratoconus, and he finds scleral lenses that vault over the intrastromal segments particularly helpful in this group. “With severe keratoconus, Intacs rarely provide the full correction needed. We use scleral lenses to make up the difference, and they really work well.” For keratoconus patients who have not had other correction, Dr. Kastl usually prescribes a specialized RGP lens such as Soper (LifeStyle Gp) or Rose K (Menicon).

The PROSE approach. The most dramatic demonstrations of how patients can be helped by a large-diameter lens have come from the fully customized PROSE (Prosthetic Replacement of the Ocular Surface Ecosystem; Figs. 1 and 2) treatment, from the Boston Foundation for Sight, a nonprofit organization founded in 1992 by Perry Rosenthal, MD.

Stephen C. Pflugfelder, MD, in his Jackson Memorial Lecture on tear dysfunction at the Academy’s 2011 Annual Meeting, said that “for severe corneal epitheliopathy from tear dysfunction, the PROSE, a specially designed scleral-bearing contact lens with a fluid-filled reservoir over the cornea, has proven to be an excellent option for improving irritation symptoms and visual acuity. ... Patients may experience almost immediate relief in photophobia and irritation symptoms after placing the device on the cornea.”7

About 1,000 people were fitted with PROSE devices last year at the foundation’s clinic in Massachusetts and at a dozen partner clinics in the United States and overseas, Dr. Jacobs said. The customization process takes typically one to two weeks, during which patients are evaluated, fitted and trained by a multidisciplinary team, including cornea specialists, ophthalmologists, optometrists, trainers and device manufacturing engineers. Because of the degree of customization, the lenses cost approximately $5,000 per eye; however, much of this cost may be covered by medical insurance or financial assistance from the foundation.

“It’s our approach to the underlying pathology that makes PROSE unique for patients with complex corneal disease,” Dr. Jacobs said. “It’s an innovative treatment model, and it doesn’t really fit into conventional models of how eye care is delivered or of how contact lenses are fitted,” she said. “It’s not a matter of just fitting devices from a trial set. It’s a customization process based on what the team determines are the physiological, functional and visual needs of the patient.”

More widely available sclerals. Patients with less severe cases of dry eye, keratoconus and irregular astigmatism can turn to commercially available scleral contact lenses.

“The PROSE device is impressive: It’s definitely the Rolls-Royce of scleral devices. But not everybody needs a Rolls-Royce. Some people just need a Honda,” said Muriel Schornack, OD, who does scleral lens fittings for Dr. Patel and other Mayo ophthalmologists.

Dr. Schornack, a consultant in the department of ophthalmology and assistant professor of ophthalmology at the Mayo Clinic, has fitted 220 patients with Jupiter scleral lenses (Medlens Innovations/ Essilor) since 2006.

The total cost for bilateral lenses and the fitting fee is between $2,000 and $3,000, Dr. Schornack said. She uses a diagnostic set of trial lenses to determine the proper sagittal depth and then does overrefraction to obtain lens power. If the basic lens design needs to be altered to provide an optimal fit, the back surface peripheral curve system can be customized.

This is not unduly complex, she said, and may not be significantly more time-consuming than other specialty contact lens fits. In a 2010 paper about a series of 19 keratoconus patients, she and Dr. Patel reported ordering 1.5 lenses per eye and seeing patients a mean of 2.8 times before achieving a good fit for all of them.6

The Comfort Factor

Better scleral fitting with optical coherence tomography. The most common complaint patients have about scleral lenses is that they feel tight and uncomfortable around the periphery.

By using OCT, researchers at Oregon’s Pacific University think they have found the reason: The sclera is much flatter than generally recognized.

“We have been trying to get a better handle on the ideal scleral shape these lenses should have. And it is not curved,” said Patrick J. Caroline, COT, a specialty contact lens fitter and assistant professor of optometry at Pacific University, in Forest Grove, Ore.

He said that OCT imaging of more than 100 normal and diseased eyes uniformly showed that the sclera is nearly flat, out to a diameter of about 22 mm—yet the peripheral zone of today’s scleral lenses is curved.

“The lens literally pinches the eye,” said Mr. Caroline. “The ocular anatomy textbooks we’ve been using for many, many years do not have an accurate description of the sclera. But we’ve got it now, so we can move forward with new designs.”

Hybrid lenses. Other additions to the large-diameter class of contact lenses are hybrid lenses, which take a different approach to comfort by using an RGP optical zone surrounded by a skirt of softer silicone hydrogel.

SynergEyes, of Carlsbad, Calif., made its early hybrid lenses out of RGP and HEMA and marketed them for keratoconus patients (SynergEyes KC and ClearKone). But after switching to silicone hydrogel for the skirt, the company is now also making its 14.5-mm lenses for healthy eyes with up to 20 D of myopia or hyperopia plus astigmatism (Duette) or presbyopia (Duette Multifocal).

Dr. Kastl considers hybrid lenses a reasonable approach for patients “who want the vision of RGPs and the comfort of soft lenses.” However, he thinks that their price could be a barrier for many patients, especially because their soft skirts may render them more vulnerable to damage than completely hard lenses.

Safety Considerations

Oxygen is highly transmissible through the RGP materials used in today’s large lenses, which alleviates earlier problems of corneal hypoxia. But that doesn’t eliminate all safety concerns.

What about complications? In the medical literature, there are no adverse events or complications reported for contact lens papers indexed with a “scleral” keyword. But there are two reports of serious complications in wearers of hybrid lenses. In one case, three patients contracted bilateral Acanthamoebakeratitis. Two of the six eyes required penetrating keratoplasty for dense corneal scarring.8

In the other case, five people developed epithelial edema (central corneal clouding) within the first five hours after being fitted with a hybrid contact lens for keratoconus. Refitting succeeded for two patients, while two discontinued lens wear entirely and one patient was able to wear lenses on a limited basis.9

“Normal” eyes might be next. Meanwhile, Dr. Schornack worries that enthusiasm over the early results is creating pressure to lower the clinical threshold for scleral or hybrid contact lenses. Indeed, the FDA’s approval of the SynergEyes Duette hybrid marked the first time that a scleral-supported lens received labeling solely for refractive error rather than for a pathologic condition.

“If we start to use these devices as first-line therapy for dry eye or correction of simple refractive error before we more fully understand their impact on the ocular surface, we could be placing patients at risk for complications,” she said. “I would prefer to think of scleral lenses as medical devices rather than elective or cosmetic lenses.”

Dr. Patel said he is comfortable suggesting the scleral option to people who are troubled by their dry eye symptoms after other therapies for dry eye have failed. “We will fit them with scleral lenses, but with such patients, success often depends on how motivated they are,” he said.

Dr. Kastl said that he does not have any special safety concerns about scleral or hybrid lenses, as long as they are not used for extended wear.

Innovations in Hydrogel Lenses

Meanwhile, research has continued to expand the range of patients—including those with astigmatism or keratoconus—who can obtain improved vision with soft lenses.

Better Torics

Twenty years ago, when an optical center ordered toric hydrogel contact lenses for a patient, luck as much as skill determined the quality of the lenses that came back.

Conquering inconsistency. “Lack of consistency in the production of toric hydrogel lenses used to be a major issue. You’d find a lens that worked perfectly for a patient but could never count on getting another lens that worked as well,” Dr. Schornack recalled. “We used to discourage patients with minimal astigmatism from trying toric lenses because of the lack of stability and reproducibility. Now, I routinely prescribe toric lenses for patients with as little as 0.75 D of astigmatism.”

Greater precision. Today’s contact lens production processes are much more precise, and vision scientists know more about the optics of the cornea and lens. These advances have made it much easier for eye care practitioners to meet the out-of-the-ordinary refractive needs of their patients.

Toric contact lenses for daily wear are offered for very high levels of astigmatism: up to –12 D in silicone hydrogel lenses (Intelliwave Aspheric Toric, Art Optical) and up to –16 D in soft hydrogel (Fre-Flex Special Design Toric, Ocu-Ease/Optech). And the Gelflex Custom Toric MTO (Gelflex Laboratories) offers “unlimited” cylinder.10

Customized Soft Lenses for Keratoconus

Until this fall, only small amounts of customization were offered for hydrogel lenses sold in the United States. This changed in October, with the introduction of the first soft, fully customizable keratoconus lenses made out of a silicone hydrogel (hioxifilcon D).

Because the material can be lathed, the posterior surface of NovaKone lenses (Alden Optical) can be precisely shaped to neutralize irregular astigmatism and optimize lens fit, according to the company. A toric front surface corrects for regular astigmatism up to –10 D, and spherical power can be from +30 D to –30 D.

Mr. Caroline, who has fitted NovaKone lenses, said his keratoconus patients have had some surprising optical results with them. “It doesn’t make a lot of sense that a soft contact lens would work as well optically as an RGP lens, but in many cases we’re finding that patients’ vision with this lens is even better than it is with an RGP.” This might be because the NovaKone optic centers better over the pupil, he said.

And by the first quarter of 2012, another fully customizable silicone hydrogel for keratoconus is expected to be available in the United States. KeraSoft lenses (Bausch + Lomb) will be made to order, the company has said.

___________________________

1 Romero-Rangel T et al. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000;130(1):25-32.

2 Segal O et al. Cornea. 2003;22(4):308-310.

3 Rosenthal P, Croteau A. Eye Contact Lens. 2005;31(3):130-134.

4 Visser ESR et al. Eye Contact Lens. 2007;33(1):13-20.

5 Tougeron-Brousseau B. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;148(6):852-859.e2.

6 Schornack MM, Patel SV. Eye Contact Lens. 2010;36(1):39-44.

7 Pflugfelder SC. Am J Ophthalmol. 2011 Oct 24 [Epub ahead of print].

8 Lee WB et al. Eye Contact Lens. 2010;36(3):164-169.

9 Fernandez-Velazquez FJ. Eye Contact Lens. 2011;37(6):381-385.

10 2011 Contact Lens & Solutions Summary. Supplement to Contact Lens Spectrum, July 2011.

Meet the Experts

PATRICK J. CAROLINE, COT Assistant professor of optometry at Pacific University in Forest Grove, Ore. Financial disclosure: Consults for Paragon Vision Sciences.

DEBORAH S. JACOBS, MD Medical director of the Boston Foundation for Sight in Needham, Mass.Financial disclosure: Is a full-time, salaried employee of the nonprofit foundation; has no proprietary or financial interest in any contact lens or prosthetic device.

PETER R. KASTL, MD, PHD Professor of ophthalmology at Tulane University, New Orleans. Financial disclosure: None.

SANJAY V. PATEL, MD Associate professor of ophthalmology at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.Financial disclosure: None.

MURIEL SCHORNACK, OD Consultant in the department of ophthalmology and assistant professor of ophthalmology at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. Financial disclosure: None.

|