By Harmeet S. Gill, MD, FRCSC, Richard Imes, MD, and Rona Z. Silkiss, MD, FACS

Edited by Thomas A. Oetting, MD

This article is from June 2012 and may contain outdated material.

Just before he retired, John Graham* began experiencing mild headaches and felt that he couldn’t see as clearly as he used to. He wasn’t all that worried about it and continued to focus on wrapping up his work life. However, one morning, the 64-year-old awoke with a headache that was worse than usual and could not “rub the sleep out of his eyes.” This prompted a visit to the optometrist, who discovered bilateral swelling of the optic nerves and immediately referred Mr. Graham to our neuro-ophthalmology service.

We Get a Look

Mr. Graham reported headaches and bilateral blurred vision that had progressed over two months. He also reported no previous eye problems except the need to use +3.00 readers while working.

With regard to his general health, Mr. Graham told us that most of his time was spent at his desk and that he got out once or twice a year to enjoy a round of golf. He noted that he suffered from snoring and obstructive sleep apnea, which was not being treated, and that he took medication for hypertension and type 2 diabetes. He sheepishly acknowledged that the combination of a relatively sedentary lifestyle plus a fondness for rich foods and wine was the culprit behind his high body mass index. In a word, Mr. Graham was obese. This had resulted in some chronic lower back pain that he managed with muscle relaxants and acetaminophen as necessary.

We found that Mr. Graham’s BCVA was 20/70 in his right eye and 20/40 in his left. His anterior segment, IOP, pupillary examination, and ocular motility all were normal. The dilated funduscopic exam revealed bilateral blurred disc margins and peripapillary exudate and hemorrhage (Figs. 1A and 1B).

|

|

|

Bilateral Trouble. Optic disc photographs of the patient’s left (1A) and right (1B) eyes demonstrated blurred margins, exudates, and hemorrhages consistent with papilledema.

|

Potential Causes

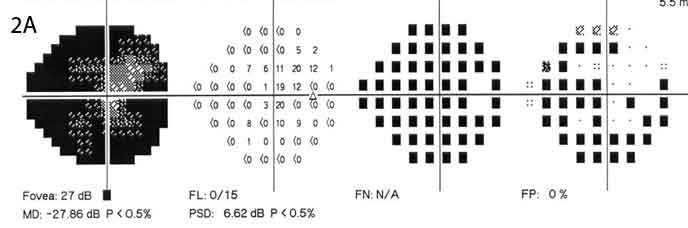

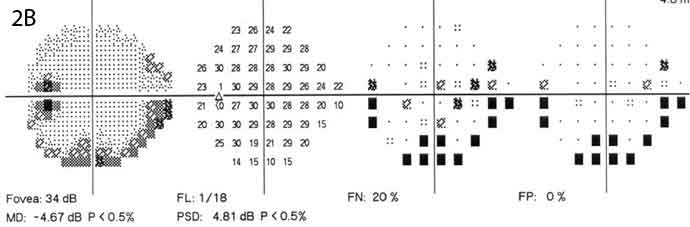

Given Mr. Graham’s new-onset headaches and bilateral optic disc edema, our working diagnosis was elevated intracranial pressure (ICP). We considered other diagnoses but felt them to be much less likely. These included posterior uveitis, optic neuritis, hypertensive disc edema, diabetic papillopathy, ischemic optic neuropathy, infiltrative optic neuropathy, scleritis, and thyroid-related eye disease. Perimetric testing found deficits that were worse in Mr. Graham’s right eye than in his left (Figs. 2A and 2B).

Mr. Graham was referred for a full neurological evaluation and underwent neuroimaging. No focal neurological deficits were detected. MRI, ordered with and without gadolinium, ruled out an intracranial mass and infiltrative disease. The ventricles were normal in size, but the optic nerve sheaths were enlarged bilaterally. Magnetic resonance venography (MRV) showed no evidence of venous sinus thrombosis.

Finally, a lumbar puncture was performed with Mr. Graham lying in the lateral decubitus position; this found normal cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) composition but elevated opening pressure.

|

|

|

Additional Evidence. Perimetric testing found deficits that were worse in the right eye (2A) than in the left (2B).

|

Pinning Down the Diagnosis

Based on these findings, Mr. Graham was diagnosed with idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH).

IIH, previously known as pseudotumor cerebri and benign intracranial hypertension, has an annual incidence of 1 or 2 persons per 100,000. Permanent vision loss is the major morbidity, and blindness occurs in up to 10 percent of patients.1

At present, the diagnosis of IIH is based on the modified Dandy criteria, which were updated in 2002. Mr. Graham fulfilled all of the criteria: 1) signs and symptoms of elevated ICP, 2) normal neuroimaging, 3) absence of localizing signs except abducens palsy, and 4) elevated CSF pressure with normal CSF composition.

A Look at IIH

Etiology. Even though IIH has been recognized as a clinical entity for more than 100 years, the etiology of increased ICP in the absence of intracranial pathology remains unclear. Although obesity is not the cause of IIH, many studies have demonstrated a strong association, which is of concern given the increasing prevalence of obesity in the United States.

Other factors implicated in the development of IIH include hormonal changes, abnormal CSF inflow or outflow, and thrombotic or coagulation disorders. These conditions appear to contribute to increased venous sinus pressure and poor CSF absorption.

Because the cranial vault has a fixed volume, as ICP rises, the venous sinus volume is reduced, which reduces the amount of CSF absorbed. This, in turn, elevates ICP, resulting in a positive feedback loop. The optic nerve is a white matter tract of the central nervous system surrounded by CSF for its entire length. Any increase in ICP also increases the pressure within the subarachnoid space of the optic nerve sheath. The result, for many patients, is optic nerve swelling and damage to retinal ganglion cell axons.

Demographics and symptoms. Although most patients with IIH are obese females of reproductive age, the condition may be seen in children and adult men and women of normal weight. Secondary causes of elevated ICP should be ruled out. These include steroid withdrawal, vitamin A toxicity, endocrine disorders (notably Addison disease), and various medications (such as tetracyclines and nitrofurantoin).

Patients typically present with blurry vision or vague visual complaints. Up to 90 percent of patients will report a generalized headache that is most severe in the morning. Other symptoms may include transient visual obscurations, horizontal binocular diplopia, pulse-synchronous tinnitus, or nausea and vomiting. Obstructive sleep apnea, which is more common in obese males, also is associated with IIH.

Clinical exam. Many IIH patients demonstrate bilateral optic disc swelling. The blurred optic disc margins can range from mild to severe and can be asymmetric. Patients may also exhibit an abduction deficit secondary to an abducens (VI) nerve palsy. All patients should have a full neuro-ophthalmic workup that includes visual acuity, visual field testing, and optic nerve evaluation. Visual field deficits are variable, and testing should be repeated every two to four weeks until stabilization.

Neuroimaging. Standard MRI will detect most intracranial processes that raise ICP. Typical findings in IIH include an empty sella, slit-like ventricles, an enlarged optic nerve sheath, and concavity or flattening of the posterior globes. A reduced diameter of the cavernous sinuses may also be seen. An MRI with gadolinium should be ordered to help rule out meningeal infiltrative disease, which can mimic IIH.

MRV or computed tomographic venography should be ordered to rule out subtle venous sinus thrombosis. MRV may also demonstrate venous sinus stenosis, which is seen in up to 90 percent of IIH cases.2

Lumbar puncture. After an intracranial mass is ruled out on neuroimaging, lumbar puncture is performed with the patient lying in the lateral decubitus position. An opening pressure greater than 25 cm H20 in an obese patient with a normal CSF composition supports the diagnosis of IIH. Lumbar puncture is both diagnostic and therapeutic, as it lowers ICP for a variable interval.

Treatment of IIH

In some cases, IIH may resolve without intervention. Only symptomatic patients with evidence of visual deficit, papilledema, or intractable headaches require treatment.

Although an individualized approach should be developed for each patient based on the symptoms (vision loss versus intractable headaches), their severity, and underlying medical conditions, there are three broad categories of treatment:

Weight loss. Through diet and exercise, all obese patients should aim for a reduction of total body weight by at least 5 to 10 percent. Mild fluid restriction and a low-sodium diet may also prove helpful. Patients who are morbidly obese should consider bariatric surgery.

Medication. All symptomatic patients without known contraindications may be treated with oral acetazolamide (250 to 500 mg, twice daily) or furosemide (20 to 80 mg, once to twice daily). Patients with intractable headaches may respond to topiramate (25 mg, once daily), which has the additional benefit of appetite suppression. Intravenous steroids or acetazolamide may be considered for cases of acute visual deterioration as a temporizing measure before surgical intervention. Steroid therapy in IIH is controversial.

Surgery. In 20 percent of cases, lifestyle modification and pharmacologic therapy will be insufficient. When this is the case, serial lumbar punctures can be used as a temporizing measure before a definitive intervention such as optic nerve sheath decompression (ONSD) or CSF diversion surgery is performed.

Which Surgery Is Best?

There remains an ongoing debate regarding whether ONSD or CSF diversion surgery is the preferred management option. A lack of prospective randomized studies makes this decision unclear. Ultimately, the choice will depend on the expertise of the surgeon.

ONSD. When vision loss is the primary symptom, as it was for our patient, ONSD is a reasonable option, as it improves visual acuity, visual fields, and papilledema in more than 90 percent of patients. In fact, unilateral surgery can improve the status of both eyes, presumably due to decompression of the subarachnoid space around both optic nerves.3

However, ONSD is associated with complications in up to half of all cases. These include damage to the optic nerve arterial supply (11 percent), temporary motility disorders (29 percent), pupillary abnormalities (11 percent), and symptom recurrence.4 Delaying surgical intervention (even by hours to days) and/or poor baseline vision tend to confer a worse prognosis.

CSF diversion surgery. In cases of vision loss and/or headaches, neurosurgery may be consulted to consider lumbar-peritoneal or ventriculo-peritoneal shunting, which treat the underlying problem of elevated ICP by connecting the subarachnoid space of the lumbar spinal cord or ventricles to the abdominal peritoneal cavity.

The main disadvantages are the high failure and complication rates. Typically, more than 50 percent of patients will require shunt revision due to migration, infection, or low-pressure headaches. In addition, there is a 0.9 percent mortality rate associated with lumbar-peritoneal shunting.

Advances in neurosurgical techniques have introduced procedures such as endovascular dural venous sinus stenting, which show promise as a management option for IIH.

Follow-Up Schedule

IIH patients must be followed regularly with visual field testing and examination of the optic discs. Initially, this should be performed every two to four weeks until stabilization; after that, it may be done every six months. Patients should continue to be counseled regarding the value of ongoing weight loss and may require additional pharmacotherapy or surgery if symptoms persist or recur. Newer noninvasive modalities useful in following patients include transcranial doppler for ICP evaluation and OCT for retinal nerve fiber layer analysis.

Our Patient’s Progress

Mr. Graham was counseled to lose weight and was placed on oral acetazolamide (500 mg, twice daily). He also received continuous positive airway pressure treatment for his sleep apnea following a sleep study.

Despite these interventions, his visual deficit progressed. The decision was made to proceed with unilateral ONSD of the right eye, and the papilledema resolved dramatically in both eyes by the first postoperative week.

___________________________

* Patient’s name is fictitious.

___________________________

1 Banta JT, Farris BK. Ophthalmology. 2000;107(10):1907-1912.

2 Dykhuizen MJ, Hall J. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2011;22(6):458-462.

3 Alsuhaibani AH et al. Ophthalmology. 2011;118(2):412-414.

4 Plotnik JL, Kosmorsky GS. Ophthalmology. 1993;100(5):683-690.

___________________________

Dr. Gill is a fellow in orbital and oculofacial plastic surgery, Dr. Imes is chief of neuro-ophthalmology, andDr. Silkiss is chief of ophthalmic plastic, reconstructive, and orbital surgery; all are at California Pacific Medical Center in San Francisco. The authors report no related financial interests.