By Brett Gudgel, MD, James O’Brien, MD, Annie Moreau, MD, and Jo Elle G. Peterson, MD

Edited By: Ingrid U. Scott, MD, MPH

Download PDF

Michael Gusterson* set down his newspaper in frustration. The 74-year-old Caucasian man had been having an increasingly difficult time reading for the past month. The words on the page appeared double, causing Mr. Gusterson to close his right eye to eliminate that annoying symptom. To add insult to injury, his wife had mentioned that his right eye appeared to be bulging, although he couldn’t perceive it himself when he looked in the mirror.

Fed up with his inability to read, Mr. Gusterson visited a local ophthalmologist to get some answers, which led to his referral to our neuro-ophthalmology service.

We Get a Look

History. Mr. Gusterson described his double vision as horizontal and binocular. He felt that it had been getting worse over the past month. He said that he did not have double vision at distance, and there was no associated pain. Over the previous month, several people had told him that his right eye had a bulging appearance, and they said that this had become more pronounced as the weeks went by.

Further discussion of his medical history revealed that Mr. Gusterson had been told 10 years earlier that he might have multiple myeloma. However, he reported that he had been “misdiagnosed” and never received treatment.

On reviewing his records, we found that Mr. Gusterson had been diagnosed with monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS). He also had a history of well-controlled hypertension and depression, with no history of ocular problems. He had formerly smoked two packs of cigarettes each day, and was still using chewing tobacco.

Exam. Mr. Gusterson’s best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) measured 20/50 in his right eye (with +2.75 + 0.75 × 175 correction) and 20/25 in his left (with +0.75 + 2.00 × 165 correction). His pupils were equal, round, and reactive to light, with no relative afferent pupillary defect. Intraocular pressures were 20 mm Hg in the right eye and 13 mm Hg in the left.

Motility testing showed –2 to –3 ductional deficits in all directions of gaze with the right eye and full motility with the left eye (Fig. 1). Forced duction testing was positive on the right. The patient’s alignment in primary gaze was 4 prism diopters (PD) of exotropia (XT) and 6 PD of right hypotropia at distance, and 16 PD of XT at near. External exam showed proptosis of the right eye, which measured 27 mm on Hertel exophthalmometry, compared with 20 mm for the left eye.

The anterior segment exam was significant for 2+ nuclear sclerotic cataracts bilaterally. The fundus exam showed choroidal striae in the macula of the right eye.

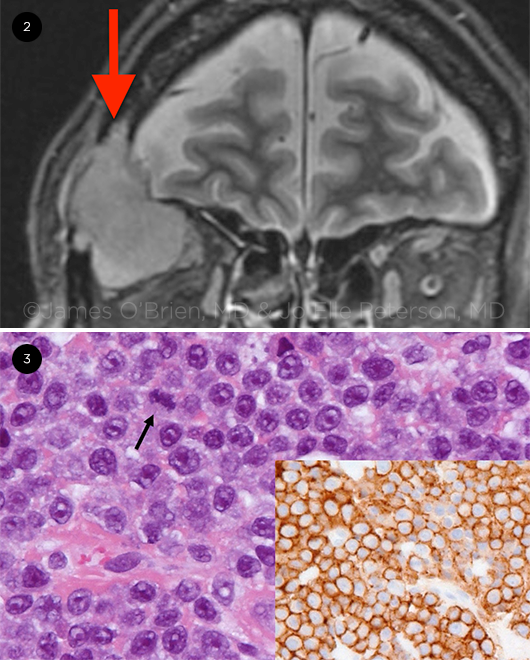

Imaging. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the orbits was ordered. The scan showed an enhancing mass in the right superior and lateral orbit measuring 4.3 cm in diameter, displacing the right superior and lateral rectus muscles as well as the right optic nerve. Bony destruction of the right superior and lateral orbital walls was noted as well (Fig. 2).

|

|

OCULAR MOTILITY. Series of images shows limitation of ductions with the right eye in all directions of gaze.

|

Diagnosis

Differential. The initial differential diagnosis included metastatic disease, lymphoma, plasmacytoma, pleomorphic adenoma, and adenoid cystic carcinoma. A biopsy was ordered to obtain a histologic diagnosis. Computed tomography (CT) of the orbits was performed for surgical planning, and the patient was referred to the oculoplastics service.

Making the diagnosis. Following his CT scan, Mr. Gusterson underwent successful anterior orbitotomy with biopsy. Surgical pathologic analysis revealed a monomorphous population of cells with minimal to moderate cytoplasm and prominent nucleoli. Immunohistochemical staining and flow cytometry studies were consistent with a plasma cell neoplasm (Fig. 3). The diagnosis of orbital plasmacytoma was made.

|

|

IMAGING AND PATHOLOGY. (2) MRI reveals an enhancing mass (arrow) in the right superior and lateral orbit, displacing the right superior and lateral rectus muscle and the right optic nerve. (3) Hematoxylin and eosin–stained image (H&E, 40×) demonstrates cells with round to oval nuclei with prominent nucleoli and mitotic figures (arrow).

|

Treatment

Mr. Gusterson was referred to the hematology-oncology service, where he was diagnosed with multiple myeloma which had likely evolved from smoldering myeloma. He met the criteria for multiple myeloma, based on his orbital plasmacytoma and diffuse osteolytic lesions detected on a skeletal survey.

He underwent right orbital radiation therapy and was treated with lenalidomide and bortezomib chemotherapy. With treatment, his proptosis and diplopia resolved, and his BCVA improved to 20/40.

Discussion

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a malignancy of monoclonal plasma cells that accounts for 1.3% of all malignancies and 15% of hematologic cancers. The median age of diagnosis is 69 years. The disease has a wide and variable range of clinical features, including lytic bone lesions, anemia, hyperkalemia, and recurrent infections.1 MM is considered part of a spectrum of plasma cell dyscrasias, a group of diseases that also includes MGUS, smoldering myeloma, systemic light chain amyloidosis, and solitary plasmacytoma.2

MM can affect the eyes in a variety of ways, including corneal deposits, conjunctival and orbital plasmacytomas, iris and ciliary epithelial cysts, retinal hemorrhages, retinal vein occlusions, and exudative retinal detachments.3 Despite the variety of ocular manifestations, involvement of the orbit is rare.2 When orbital involvement is present, it is often in the form of a plasmacytoma, which is an isolated tumor of monoclonal plasma cells.

Orbital plasmacytomas can mimic other processes within the orbit, including lacrimal gland tumors, dacryoadenitis, and orbital cellulitis.4 Orbital plasmacytomas can occur in various locations, but the majority are located in the superotemporal quadrant,2 as was the case with our patient. Orbital plasmacytoma may be the initial finding in up to 75% of cases of MM with orbital involvement, with proptosis being the most common presenting symptom in the majority of cases.

Standard treatment for MM consists of chemotherapy with localized radiation therapy and bone marrow transplant as needed.2

Despite treatment, the prognosis for patients with MM is generally poor, with a five-year survival rate around 45%. However, recent advances in combination therapy may lead to better long-term disease control and perhaps eventually yield a cure.5

Subspecialty Day

Don’t miss this year’s Ocular Oncology/Pathology meeting at November’s Subspecialty Day (aao.org/2020).

|

Our Patient’s Course

Mr. Gusterson continues to receive systemic treatment from the hematology-oncology service and is thought to be in partial remission. His proptosis and diplopia have improved substantially. He developed mild eyelid dermatitis related to his orbital radiation and a left upper eyelid chalazion related to his bortezomib chemotherapy; both were treated without complication. He also developed a visually significant cataract in the right eye and subsequently underwent uncomplicated cataract surgery. His vision improved to 20/20 in the right eye without correction.

___________________________

*The patient’s name is fictitious.

___________________________

1 Jagannath S et al. Multiple myeloma and other plasma cell dyscrasias. June 1, 2016. www.cancernetwork.com/cancer-management/multiple-myeloma-and-other-plasma-cell-dyscrasias. Accessed June 9, 2019.

2 Thuro B et al. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018;34(3):258-261.

3 Knapp AJ et al. Surv Ophthalmol. 1987;31(5):343-351.

4 Russell DJ, Seiff SR. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;33(2):e32-e33.

5 Landgren O, Iskander K. J Intern Med. 2017;281(4):365-382.

___________________________

Dr. Gudgel is an ophthalmology resident, Dr. O’Brien is an assistant professor of ophthalmology, and Dr. Moreau is an associate professor of ophthalmology; all three are at the Dean McGee Eye Institute in Oklahoma City. Dr. Peterson is an assistant professor of pathology at the University of Oklahoma. Financial disclosures: None.