By Megan Rowlands, MD, MPH, Irina Belinsky, MD, and Yasha S. Modi, MD

Edited By: Steven J. Gedde, MD

Download PDF

Tabitha Tisch* was anxious. The 53-year-old woman had been struggling to cope with a number of health conditions—including myasthenia gravis, hyperthyroidism, and fibromyalgia—but this was different. At home, one Saturday morning, she was struggling to find words, had episodic diplopia, and was experiencing difficulty typing. This resolved a few hours later, but since she had never experienced something like this before, she rushed to the nearest emergency department.

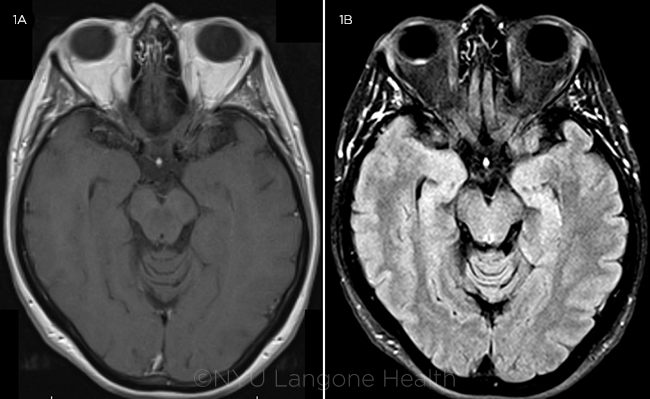

Given the concern for a cerebrovascular event, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain was performed, which was normal except for incidental thickening along the posterior aspect of the right globe (Figs. 1A and 1B).

First Impressions

Shortly after her ER visit, Ms. Tisch was referred to our ophthalmology clinic. Her vision was 20/20 in both eyes, her pupils were equally reactive without an afferent pupillary defect (APD), and her intraocular pressure (IOP) was 8 mm Hg in both eyes. The anterior segment examination was normal.

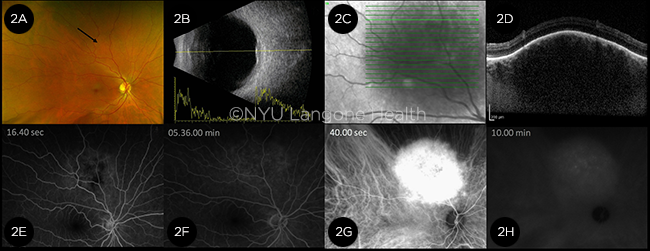

Although the fundus exam of the left eye was unremarkable, the right eye revealed an elevated, well-circumscribed, ovoid lesion with an underlying orange hue. It was superior to the optic disc measuring 5 × 6 mm in diameter (Fig. 2A, arrow).

On ultrasonography, the lesion was acoustically solid with medium-to-high internal reflectivity on A-scan (Fig. 2B). Enhanced-depth imaging optical coherence tomography (EDI-OCT) showed elevation of the retina by a hyporeflective choroidal mass, with some attenuation of the overlying photoreceptor layers, minimal posterior shadowing, and visible vessels (Figs. 2C and 2D). The mass demonstrated no intrinsic hyper- or hypoautofluorescence on fundus autofluorescence, but it did show increasing hyperfluorescence on fluorescein angiography (FA) that increased in intensity and faded during recirculation (Figs. 2E and 2F). Indocyanine green angiography (ICGA) demonstrated early hypercyanescence with late “washout” isocyanescence (Figs. 2G and 2H).

|

|

MRI. (1A) T1 and (1B) FLAIR sequences reveal slight focal thickening along the posterior aspect of the right eye, most noticeable on FLAIR. No other obvious mass lesions were noted in either orbit, and the optic nerve sheaths were unremarkable. The mass appeared isointense to the vitreous on T1-weighted imaging and hyperintense on FLAIR.

|

Making the Diagnosis

Our differential for an amelanotic, elevated choroidal lesion in an asymptomatic patient consisted of a choroidal hemangioma, choroidal granuloma, amelanotic choroidal melanoma, or a metastasis.

Compared with amelanotic choroidal melanomas, choroidal hemangiomas tend to have a more reddish-orange hue on funduscopic examination. Additionally, on A-scan, choroidal hemangiomas typically demonstrate high reflectivity, unlike choroidal melanomas, which more frequently have low internal reflectivity.

Our suspicion for metastatic disease was low in Ms. Tisch given the clinical appearance of a solitary, unilateral lesion in a patient without a prior cancer history or associated symptoms. Thus, the reddish hue to this choroidal lesion coupled with the findings on EDI-OCT, FA, and ICGA were all consistent with a diagnosis of circumscribed choroidal hemangioma.

|

|

FURTHER IMAGING. (2A) Although difficult to appreciate on this fundus photo, examination of the right eye revealed an elevated, deep mass with a reddish hue superior to the disc and arcades (arrow). (2B) Combined B- and A-scan of the right eye showed an elevated choroidal lesion with medium-to-high internal reflectivity. (2C, 2D) EDI-OCT raster scan showed a hyporeflective choroidal mass elevating the overlying retina with posterior shadowing. (2E) FA showed increasing hyperfluorescence corresponding to the choroidal lesion that increased in intensity through 1 minute (2F) but faded subsequently in the late phases of the FA. (2G) ICGA demonstrated early hypercyanescence with (2H) late “washout” isocyanescence.

|

Discussion

Choroidal hemangiomas are benign vascular tumors typically diagnosed between the second and fourth decades of life. Most patients are asymptomatic until adulthood but can then develop blurred vision or hyperopic shifts from the anteriorly displaced retina or secondary serous retinal detachments.

Choroidal hemangiomas are classified as either circumscribed or diffuse. As the name implies, circumscribed hemangiomas appear as discrete, well-delineated tumors with a reddish hue and are typically located in the macula or peripapillary region.

Conversely, diffuse hemangiomas are more extensive within the choroid and can be associated with nonocular hemangiomas elsewhere, such as the skin, central nervous system, and in certain systemic angiomatous disorders (like Sturge Weber syndrome). They can also be associated with ipsilateral glaucoma. Given their associated ocular and systemic manifestations, diffuse choroidal hemangiomas tend to be detected in younger patients.1

Imaging

Various modalities can be used to further characterize choroidal hemangiomas.

FA. On FA, choroidal hemangiomas characteristically show linear areas of hyperfluorescence in the early arterial phases followed by diffuse leakage in the later arterial and venous phases.

ICGA. On ICGA, choroidal hemangiomas typically demonstrate a lacy, diffuse pattern of hypercyanescence in the early phases followed by washout of the cyanescence within the tumor.1

MRI. Use of MRI is not always helpful in differentiating choroidal tumors, especially when they are too small to visualize and evoke a signal, but it can be complementary to ophthalmic imaging in the setting of diagnostic uncertainty. Choroidal hemangiomas are hyperintense to vitreous on T1 and isointense on T2.2 In our case, the hemangioma was not well identified on either sequence, which may in part be due to its small size of < 2 mm thickness on ultrasonography. It was most conspicuous and hyperintense on T2–fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) imaging. Damento et al. recently highlighted the utility of T2-FLAIR sequence for increased conspicuity and identification of certain choroidal tumors, including uveal melanoma and choroidal hemangioma, both of which show T2-FLAIR hyperintensity.3

Frequent misdiagnoses. Even with these characteristic imaging findings, differentiating between choroidal hemangiomas and other choroidal lesions, namely choroidal melanomas, remains challenging, and these tumors can often be misdiagnosed.4

EDI-OCT shows promise. In a review of various choroidal tumors imaged with EDI-OCT, several key features were noted. All choroidal melanocytic tumors—for example, choroidal nevi, choroidal melanomas, and optic disc melanocytomas—displayed a band of high reflectivity with posterior shadowing. By comparison, choroidal hemangiomas demonstrated low to medium reflectivity, and choroidal metastases were typically low in reflectivity. In addition to the differing degrees of reflectivity, the lesions differed in terms of the appearance of adjacent photoreceptor layers. For example, choroidal melanocytomas and choroidal nevi demonstrated loss of the overlying photoreceptor layers, whereas the choroidal melanomas, hemangiomas, osteomas, and metastases displayed “shaggy” photoreceptor layers.5 Also, the choroidal vessels are usually visible on EDI-OCT of choroidal hemangiomas, while they tend to be compressed and not visible in the case of choroidal melanoma.

Treatment

Treatment of choroidal hemangiomas depends on the severity of symptoms and presence of retinal detachment. Asymptomatic patients do not require treatment but rather can be observed. In symptomatic cases, hemangiomas may be treated with photodynamic therapy (PDT), photocoagulation, external beam radiation, or transpupillary thermotherapy. PDT is the preferred treatment, particularly for lesions that involve the macula. Intravitreal anti–vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) treatments and oral propranolol have also been used successfully in some cases to resolve associated subretinal fluid.6,7

Patient’s Course

Because Ms. Tisch remained asymptomatic with stable vision and without the presence of subretinal fluid or detachment, we decided to observe her. A comprehensive workup of her transient neurologic symptoms was negative, and her symptoms did not recur. We advised her to monitor for any visual changes, including blurred vision and metamorphopsia, and we plan to see her again in 3 months for a repeat dilated exam and EDI-OCT.

___________________________

* Patient name is fictitious.

___________________________

1 Shanmugam PM. Ramanjulu R.. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2015;63(2):133-140.

2 Stroszczynski C et al. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1998;19(8):1441-1447.

3 Damento GM et al. Ocul Oncol Pathol. 2016;2(4):251-261.

4 Campagnoli TR et al. Retin Cases Brief Rep. 2016;10(2):175-182.

5 Cennamo G et al. Eye (Lond). 2017;31(6):906-915.

6 Shoeibi N et al. Ocul Immun Inflamm. 2011;19(5):358-360.

7 Arevalo JF et al. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129(10):1373-1375.

___________________________

Dr. Belinsky is a specialist in oculoplastics and ocular oncology, and is a clinical assistant professor, Dr. Modi is a vitreoretinal surgeon and an assistant professor, and Dr. Rowlands is a first-year ophthalmology resident; all three are at the department of ophthalmology at New York University Langone Health. Relevant financial disclosures: None.