By Jeff H. Pettey, MD, with Usiwoma E. Abugo, MD, O’Rese J. Knight, MD, and Grace Sun, MD

Download PDF

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a profound effect on training programs in the United States. In Part 2 of this roundtable, Jeff H. Pettey, MD, of the John A. Moran Eye Center at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, hosts a discussion with Usiwoma E. Abugo, MD, of Virginia Eye Consultants and Eastern Virginia Medical School in Norfolk; O’Rese J. Knight, MD, of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; and Grace Sun, MD, of Weill Cornell Medical College in Manhattan. They talk about issues resulting from stalled rotations, the next step for residents, and some upsides of adapting to the pandemic.

Stalled Rotations

Dr. Pettey: The pandemic has affected medical student clinical rotations, and the repercussions of this are now top of mind for many prospective students and educators. How has this played out at your institution?

Dr. Knight: Specifically, for medical students, we canceled our onsite research and clinical rotations in coordination with the medical school, and that happened about mid-March. The University of North Carolina (UNC) students returned to clinical rotations at the end of June, and we’ve welcomed them back into our eye clinic.

With regard to away rotations, UNC is following the Coalition for Physician Accountability (CPA) guidelines. The CPA has recommended that “for the 2020-2021 academic year, away rotations be discouraged, except for learners who have a specialty interest and do not have access to a clinical experience with a residency program in that specialty in their school’s system or for whom an away rotation is required for graduation or accreditation requirements.” This is an important time in the application cycle for students to complete away rotations to pursue research opportunities, develop relationships with mentors who can write letters of recommendation, and explore the programs to which they may apply. However, like many institutions, we’re not offering onsite rotations to non-UNC students. We have some students who have been able to complete research rotations given the nature of their study—for example, chart reviews or optical coherence tomography imaging studies. Some ophthalmology departments are inviting visiting medical students from institutions without a department of ophthalmology. However, this does not address the students’ concerns for their personal safety, pandemic-related changes in life circumstances, variable state-to-state quarantine restrictions, or restrictions from their home institutions. So there are logistical questions about whether these rotations can be completed.

The idea of postponing the match to accommodate delays in student rotations is of particular interest to me. Aside from difficulties in completing ophthalmology electives, students are also navigating disruptions in United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) accessibility. The USMLE Step 2 Clinical Skills (CS) program has been suspended indefinitely. Many students have had to significantly delay sitting for their USMLE Step 2 Clinical Knowledge examinations. The latter may become increasingly important to ophthalmology as the score reporting for the USMLE Step 1 examination is transitioning to Pass/Fail as of Jan. 1, 2022. As a community of ophthalmology educators, we need to consider the way we define qualified and competitive applicants. In the immediate term we will be faced with applicants with either no Step 2 CS exam or a failing score that has not been remediated, fewer ophthalmology-specific letters of recommendation, and less clinical and/or research experience. There are some aspects of students’ applications that we will need to rethink. It will be important to individually evaluate each student’s situation.

Dr. Pettey: The USMLE Step 1 change from a numeric score to Pass/Fail is a seismic shift for medical education. It takes away the single consistent metric all applicants share. Additionally, medical students have had highly variable experiences during the COVID crisis, depending on their location and the virus’ impact. As a profession, we must improve our ability to holistically assess applicants to keep the best and brightest entering our profession.

|

|

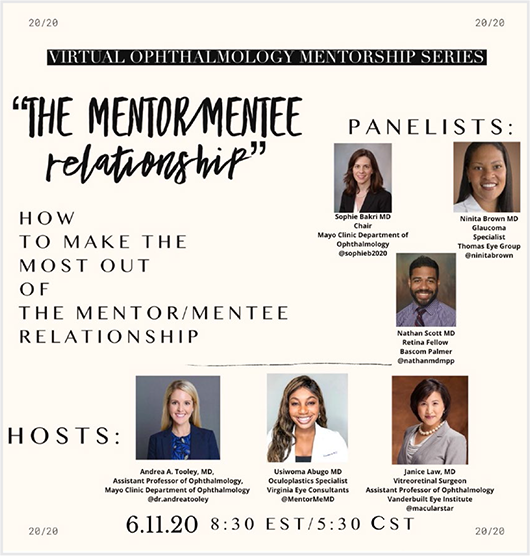

VIRTUAL MENTORING. In response to the pandemic, an ad hoc virtual mentoring program was set up to help guide students through the residency application process.

|

Fostering Diversity

Dr. Pettey: Diversifying ophthalmology is a top priority for our profession and a necessary change needed throughout medicine. Dr. Knight, would you please discuss your perspectives and ongoing work with students who are underrepresented in medicine or marginalized?

Dr. Knight: Every summer I work with underrepresented in medicine [URiM] students who are applying for ophthalmology residency through the National Medical Association’s Ophthalmology Section. We invite the students to present their research in the Rabb-Venable Excellence in Ophthalmology Research Program and participate in networking and professional development opportunities. This year, in response to COVID-19, we have expanded our offerings, and we’ve developed a near-peer mentoring system to assist the students in preparing their applications. Additionally, we’ve coordinated a series of fireside chats with program officers throughout the country to create some level of familiarity between programs and URiM applicants in what will certainly be a unique application cycle. So I’m quite excited about this, particularly given the preexisting need to increase the diversity of the ophthalmology workforce.

As far as our efforts in residency education go, I echo what Dr. Sun mentioned in terms of more collaboration and more communication across programs [see Part 1, last month]. We are certainly doing that. Duke has been very gracious in inviting us to all of its ophthalmology webinars, and we’re making every effort to maintain our tri-residency activities with Duke and Wake Forest. And I echo the fact that we’ve had more time to teach the basic principles of ophthalmology than if we’d been seeing our typical numbers of patients. In that regard, I hope that we find a way to maintain focus on education, because I think sometimes we get overwhelmed with the patient care mission, and we kind of forget the teaching mission.

Dr. Pettey: This is foundationally important work and thank you for advancing diversity in our profession.

Fellowships and Job Prospects

Dr. Pettey: With COVID’s impact on the job market, are residents postponing entry to practice in favor of additional fellowship training and a better job market in the future? What about the job market for those who have just completed fellowships? Has the current situation led to any type of renegotiation?

Dr. Sun: The overall trend is that about 75% of graduating residents are now entering a fellowship, which has been steadily increasing over the last 10 years. In our program at Cornell, about 80% of our residents do a fellowship. I don’t see that trend changing. There are more fellowship opportunities for residents, and residents report the acquisition of special skills, earning potential, and interest in an academic career as reasons to pursue a fellowship.

Whether COVID-19 will affect that trend is a good question. I’m not sure whether residents will feel like they now need a fellowship to augment their surgical skills given the possible decrease in surgical volume. That being said, we all know that one additional year doesn’t necessarily suddenly make someone a better surgeon or mean that they’ve mastered all needed skills. As we know, surgery is a lifelong process, and becoming an excellent surgeon takes many years of continued self-directed learning.

Dr. Knight: At the start of the pandemic, our residents and fellows who hadn’t found positions were concerned. Some interviews were canceled, and job offers were rescinded. Ultimately, however, the biggest effect was a delay in start dates.

Dr. Abugo: I’ve heard from recent graduates and fellows who secured their jobs earlier this year. For many of those jobs, there have been renegotiations in terms of the contract, such as the time to partnership, the bonus structure, the volume of patients, and, of course, the salary.

ACADEMY-AUPO MENTORING PROGRAM

The Minority Ophthalmology Mentoring Program aims to increase diversity in ophthalmology by helping qualified medical students who are underrepresented in medicine become competitive ophthalmology residency applicants. Students receive one-on-one mentorship, access to educational resources, and more.

Visit aao.org/minority-mentoring.

|

Silver Linings

Dr. Pettey: Have there been other changes resulting from the pandemic, as a society or within ophthalmology, that portend good things in the future?

Dr. Abugo: Despite its challenges, I think COVID has given us an opportunity, as a community of ophthalmologists, to see how our skills and knowledge can be used to better advance education, especially for our medical students. For students who cannot go to away elective programs, we’re looking at the possibility of virtual rotations. The Academy has an excellent example of this: a 10-day program that covers basic skills for physical exams, observation, and interactive history; it also includes exam questions and write-ups of patient notes. [See “Medical Student Resources on AAO.org” in Part 1, last month.] The program now requires clinical encounters in ophthalmology for those who will work in a telehealth setting—which is going to be important for all ophthalmologists, but especially for our trainees who are just learning about the ophthalmology exam.

The pandemic also has emphasized virtual interviews, which has benefits for students and institutions. What I have heard from the medical students is that this can be a positive. They don’t have to spend a lot of time and money traveling to interviews, missing important educational days to do so. From the institutional standpoint, you have a reduction in missed clinical obligations, as well as greater flexibility for scheduling the interviews.

Other things that have spawned during this time are, for example, a virtual ophthalmology mentorship program. This program was started by Dr. Andrea Tooley, Dr. Janice Law, and myself, in response to the outpour of need that we saw from medical students during this time. The need is especially great among those who do not have home ophthalmology programs; they’re missing out on a lot of opportunities. We felt a great need to connect them to mentors at an ophthalmology program who could guide them through this season of application because these students are unable to have the type of personal interaction that was crucial for us during our training. The virtual ophthalmology mentorship program matches medical students with mentors based on geography and need (research, letters of recommendation, general career advice). Both the students and mentors are elicited via an in-depth survey. The mentor then guides the students through the application process and acts as a professional sounding board.

Dr. Pettey: That is extraordinary work, and we are thankful for it. There’s clearly a need, particularly for students whose programs don’t have an ophthalmology department. A couple of years ago, the average cost per ophthalmology applicant was $6,600, according to a study from the University of Kentucky.1 It showed that a total of $4.6 million was spent by applicants in a one-year period, and that is now money in the students’ pockets that can be spent on things like webcams and lighting for their virtual interviews.

Dr. Sun: I love that—the idea of innovation arising from necessity. This COVID pandemic has pushed us to think about why we do things the way we do them. I think it’s going to change the way we practice ophthalmology. Does every chalazion need an office visit? Can we embrace the potential of telemedicine and treat some patients from their home?

With respect to education, why is residency in ophthalmology three years, or soon to be three years plus three months in an integrated or joint residency program? Does residency need to be structured based on time? Due to COVID, we graduated our residents who had not completed the final three and a half months of residency in the usual manner. They graduated based on meeting the necessary competencies as defined by the ACGME. This reflects how the three-year mark, 36 months, is an artificial construct. Some residents may be able to graduate in 33 months and others in 39 months. Why not move to a competency-based residency program? The pandemic has pushed us to think about education and other matters, including the rationale for how we train.

Dr. Pettey: What an intriguing idea to explore in the future. COVID has certainly been a catalyst to push change and drive innovation. With so many bright minds throughout ophthalmic education, we can certainly look forward to a diverse and innovative future.

___________________________

1 Moore DB. J Acad Ophthalmol. 2018;10(01):e158-e162.

___________________________

Dr. Abugo is an oculoplastic surgeon at Virginia Eye Consultants and assistant professor of ophthalmology at Eastern Virginia Medical School in Norfolk. Financial disclosures: None.

Dr. Knight is assistant professor of ophthalmology and a medical student educator at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Financial disclosures: None.

Dr. Pettey is the John A. Moran Eye Center director of education and an assistant professor at the University of Utah Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences in Salt Lake City. Financial disclosures: None.

Dr. Sun is residency program director and assistant professor of ophthalmology at Weill Cornell Medical College in Manhattan. Financial disclosures: None.

AAO.org Resources for Residents and Fellows

The Academy offers various educational resources online for residents and fellows.

1. Pathology Atlas. The Pathology Atlas offers virtual microscopy images from the field, contributed by ophthalmic pathologists. Review normal-eye anatomy and ophthalmic diseases and conditions across the spectrum of eye care (aao.org/resident-course/pathology-atlas).

2. Introduction to retinal optical coherence tomography (OCT) interpretation. This interactive online course with 20 case vignettes is designed to teach residents about the various elements and layers of a normal retina in an OCT scan, how to accurately identify and describe retinal pathologies and the location of abnormalities in OCT images, and how to diagnose retinal pathology and suggest next steps in the evaluation or treatment of eye disease (aao.org/resident-course/introduction-to-oct).

3. Cataract Master. An interactive cataract surgery decision-making simulation from Mass Eye and Ear, the Cataract Master program helps trainees learn how to respond to different real-world situations during cataract surgery by choosing which steps to perform and how to manage difficulties and complications (aao.org/cataract-master).

4. OKAP and Board review slides. Designed to help residents study for the OKAP and Board exams, these slides sets cover Basic Clinical and Science Course topics in a Q&A “flipcard” format (aao.org/okap-study-presentations).

5. Strabismus simulator. This interactive tool is designed to teach and allow for practice of basic strabismus evaluation. Simple comitant deviations are demonstrated in the current model (aao.org/interactive-tool/strabismus-simulator).

6. Retinoscopy simulator. The interactive Retinoscopy Simulator is designed for students to learn and practice the principles of retinoscopy. It provides the opportunity to visualize how light reflexes in an eye with various refractive errors and amounts of astigmatism, and from various working distances (aao.org/interactive-tool/retinoscopy-simulator).

7. Ophthalmic Education App. Use this free app to look up information in the Wills Eye Manual, review Diagnose This questions, and watch 1-minute videos from the ONE Network (aao.org/education-app).

8. Videos. Watch recorded lectures on a variety of topics for residents, updated 101 courses in each subspecialty, surgical videos, and presentations from meetings (aao.org/resident-videos).

9. Courses. Courses for residents address clinical topics as well as topics like advocacy, business management, conducting research, and more (aao.org/residents-browse?filter=course).

10. Resource locator page for surgery simulations. Start here to discover various hands-on surgery simulation tools to teach everything from skin suturing to vitreoretinal surgery (www.aao.org/simulation-in-resident-education).

|