By Pedram Goel, Odel Zadeh, Benjamin Kambiz Ghiam, MD, and Houman David Hemmati, MD, PhD

Edited By: Bennie H. Jeng, MD, and Ingrid U. Scott, MD, MPH.

Download PDF

Dry eye disease (DED) is a common ocular disorder. Its effects can be debilitating, with patients often complaining of burning, itching, irritation, and redness of the eyes. A multitude of factors can cause DED, including inflammatory disease, environmental conditions, hormonal imbalance, and use of contact lenses.1 In addition, various metabolic and autoimmune disorders such as diabetes mellitus, thyroid disease, rheumatoid arthritis, and systemic lupus erythematosus can contribute to its development.1 Because there are multiple etiologies for DED, it is crucial to identify the type of dry eye in order to prescribe an effective treatment.

Classification of DED

The Tear Film and Ocular Surface Society (TFOS) Dry Eye Workshop (DEWS) II Report, which was published in 2017, aimed to define and classify the various types of DED, evaluate its epidemiology and impact, and help guide clinical management of this disease while promoting clinical trials to develop future treatments.2

DED can be classified according to the type of deficiency in the tear film: either reduced production of the aqueous component or increased evaporation of the aqueous component; the latter is most often attributable to insufficient secretion of the lipid component. These two main etiologies of DED are known as aqueous deficiency dry eye and evaporative dry eye (EDE), respectively.2

EDE. The pathophysiology of EDE includes lid-related causes such as meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD) and blink problems, as well as ocular surface–related causes including mucin and contact lens dysfunction.2 By far, the principal cause is MGD,2 a growing problem that now accounts for up to two-thirds of all cases of dry eye.3

|

|

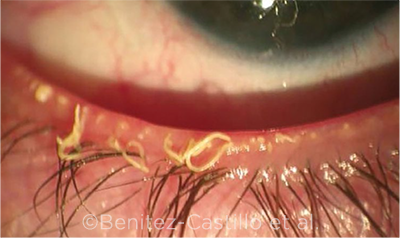

EYE WITH MGD. Strings of waxy meibum exuded from dysfunctional meibomian glands.

|

MGD

The meibomian glands, which are located in the upper and lower eyelids, secrete meibum, a protective lipid layer that prevents evaporation of the aqueous tear film. At times, these glands can become obstructed, causing ocular irritation and dry eye secondary to rapid evaporation of the aqueous tear film.

Pathophysiology. MGD is defined as “a chronic, diffuse abnormality of the meibomian glands, commonly characterized by terminal duct obstruction and/or qualitative/quantitative changes in the glandular secretion. This may result in alteration of the tear film, symptoms of eye irritation, clinically apparent inflammation, and ocular surface disease.”4 MGD typically results from increased keratinization of ductal epithelium, combined with increased viscosity of meibum.3

Management

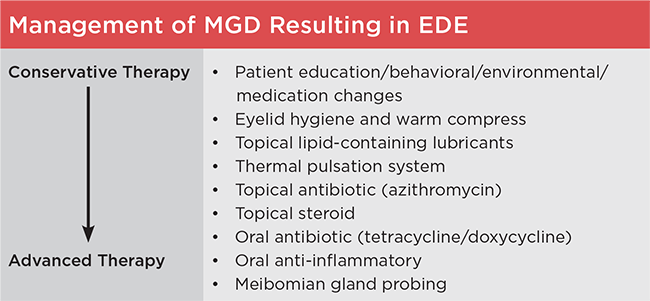

Because the pathogenesis of MGD-associated EDE varies among patients, there is no standard treatment algorithm, and management must be tailored to meet individual needs.2 Initial management should identify and treat the underlying causes of MGD, including rosacea, which can cause blockage of meibomian glands. Once that has been achieved, the treatment approach to MGD should begin with low-risk conservative management before proceeding to higher-risk advanced management. (See “Management of MGD Resulting in EDE” for our suggested general treatment algorithm for management of patients with MGD.)

Conservative management. These measures include patient education about the condition, behavioral changes such as modifications for or avoidance of exacerbating environments, reduction or elimination of medications that may worsen MGD or EDE, and the use of eyelid hygiene and warm compresses.2,5

Although dietary supplementation with omega-3 fatty acids was previously recommended as a first-line therapy for MGD, it may not be beneficial in treating MGD, according to a recent study.6

Over-the-counter eyedrops. Topical pharmacological management can target various aspects of the MGD disease process. Non–lipid-containing topical lubricants, such as preservative-free artificial tears, may provide symptomatic relief. However, the duration of their effect is typically limited to a few hours, and the treatment does not address the underlying pathophysiology of MGD.7 Instead, initial treatment should involve replacing the natural oils of the tear film with lipid-containing over-the-counter lubricant eyedrops, which may restore the balance of the tear film and provide both symptomatic relief and improvement in clinical signs of MGD and EDE with long-term use.5

Methods to improve meibum flow. Local, nonpharmacological management consists of mechanically unclogging blocked meibomian glands, thus restoring natural meibum to the ocular surface to prevent fluid evaporation. This can be done by four primary methods: warm compresses, thermal pulsation (TPS), intense pulsed light (IPL), and meibomian gland probing (discussed under “Treatment of Refractory Disease”).

Lid hygiene. The most conservative approach to increasing meibum flow is the use of warm compresses, lid scrubs, and gentle massage, performed at home by the patient.3

TPS. Thermal pulsation systems operate by applying heat to the conjunctival surfaces of the upper and lower inner eyelids while putting pulsatile pressure on the outer eyelid surfaces to express the meibomian glands. A study of 20 patients with evidence of meibomian gland obstruction suggested that treatment with TPS has benefits that are clinically evident up to three years after a single treatment.7

IPL. Several recent studies have demonstrated that IPL, a common treatment for skin rosacea, also reduces signs and symptoms of EDE in patients with MGD.8

Prescription topical drugs. Other topical agents for treating MGD include anti-inflammatory drugs (including corticosteroids) and the antibiotic azithromycin.

Azithromycin. Topical azithromycin is useful for its specific anti-inflammatory effects. One study of 22 patients with symptomatic MGD refractory to eyelid heating and massage demonstrated that topical azithromycin, when applied daily for four weeks, provided symptomatic relief and demonstrated improved signs of eyelid disease in the 17 patients who adhered to the medication regimen.9

|

|

THERAPEUTIC APPROACH. This figure lists the various treatment options for MGD-related EDE in the general order of conservative low-risk treatments to advanced higher-risk treatments. This approach is not proposed as a strict treatment protocol to be followed linearly, but rather as a guide to management that should be tailored to the individual patient’s unique pathogenesis of EDE. The listed treatments may be used individually or in combination.

|

Treatment of Refractory Disease

Corticosteroids. Brief use of weak topical corticosteroids such as fluorometholone or rimexolone may be considered to treat signs and symptoms of disease that are refractory to other treatments.3 Although topical corticosteroids do not impact the meibomian glands themselves (which are typically obstructed but not inflamed in MGD), they do reduce the secondary inflammation on the eyelid margins and ocular surface, leading to temporary relief for patients. Patients who are prescribed topical corticosteroids should be cautioned about the risks of cataract and ocular hypertension or glaucoma with prolonged use. In addition, the physician should limit refills on corticosteroid prescriptions and monitor patients for intraocular pressure elevation.

Systemic medications. Oral anti-inflammatory medications, along with oral antibiotics, comprise the systemic pharmacological management options for MGD. Because of their risks, their use should be reserved only for cases of MGD that respond inadequately to the previously mentioned local therapies.

When compared with topical azithromycin, oral doxycycline 100 mg taken twice daily for eight weeks provided relief of MGD symptoms but was not as effective as topical azithromycin in improving signs of gland plugging.10 It has been hypothesized that the mechanism by which these antibiotics improve signs and symptoms of MGD may be a result of their antibiotic properties reducing bacterial-induced inflammation or of their antilipase effects, which can explain the improvement in lipid content post-treatment.10

Intraductal probing. Meibomian gland probing, initially described by Maskin in 2010, helps to relieve obstructed meibomian glands by mechanically dilating the glands under local anesthesia.11 In a study of 25 patients, 100% had relief of symptoms four weeks after the procedure, and most patients did not require retreatment during an average follow-up of 11 months.11 This procedure can be painful, however, so it should be reserved for challenging cases that do not respond to less invasive methods.

Conclusion

The management of MGD is multifactorial and should be individualized to address the needs of each patient. The treatments described have been demonstrated to be effective for MGD and MGD-associated EDE. Clinicians may recommend a combination of therapies to treat multiple aspects of the condition.

___________________________

1 Javadi MA, Feizi S. J Ophthalmic Vis Res. 2011;6(3):192-198.

2 Craig JP et al. Ocul Surf. 2017;15(4):802-812.

3 Finis D et al. Ocul Surf. 2014;12(2):146-154.

4 Nelson JD et al. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52(4):1930-1937.

5 Geerling G et al. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52(4):2050-2064.

6 Asbell PA et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(18):1681-1690.

7 Greiner JV. Eye Contact Lens. 2016;42(2):99-107.

8 Liu R et al. Am J Ophthalmol. 2017;183:81-90.

9 Foulks GN et al. Cornea. 2010;29(7):781-788.

10 Foulks GN et al. Cornea. 2013;32(1):44-53.

11 Maskin SL. Cornea. 2010;29(10):1145-1152.

___________________________

Mr. Goel is a medical student at University of Southern California, Keck School of Medicine. Ms. Zadeh is an undergraduate student at University of California, Los Angeles. Dr. Ghiam is an ophthalmology resident at Case Western University in Cleveland. Dr. Hemmati is adjunct assistant clinical professor of ophthalmology at Roski Eye Institute, University of Southern California, Keck School of Medicine. Relevant financial disclosures: Dr. Hemmati—Allergan: O; AveroVision: C; AxeroVision: O.

For full disclosures and the disclosure key, see below.

Full Financial Disclosures

Mr. Goel None

Ms. Zadeh None

Dr. Ghiam None

Dr. Hemmati Allergan: O; AveroVision: C; AxeroVision: O; BridgeBio: C; Cell Care Therapeutics: C,O; LeoLens: O; Levation Pharma: C,O; Nevakar: C; Novateur Ventures: C; Noveome: O; Optigo Biotherapeutics: C,O; Sanguine Bio: C; Sienna Biotherapeutics: C; Viewpoint Therapeutics: C.

Disclosure Category

|

Code

|

Description

|

| Consultant/Advisor |

C |

Consultant fee, paid advisory boards, or fees for attending a meeting. |

| Employee |

E |

Employed by a commercial company. |

| Speakers bureau |

L |

Lecture fees or honoraria, travel fees or reimbursements when speaking at the invitation of a commercial company. |

| Equity owner |

O |

Equity ownership/stock options in publicly or privately traded firms, excluding mutual funds. |

| Patents/Royalty |

P |

Patents and/or royalties for intellectual property. |

| Grant support |

S |

Grant support or other financial support to the investigator from all sources, including research support from government agencies (e.g., NIH), foundations, device manufacturers, and/or pharmaceutical companies. |

|