By M. Tariq Bhatti, MD, with Larry Frohman, MD, and Gideon Nesher, MD

Download PDF

Neuro-ophthalmologist M. Tariq Bhatti, MD, at the Duke Eye Center and Duke University Medical Center in North Carolina, hosts a discussion with neuro-ophthalmologist Larry Frohman, MD, of Rutgers–New Jersey Medical School, and rheumatologist Gideon Nesher, MD, of Shaare-Zedek Medical Center and Hebrew University in Jerusalem. The trio share thoughts on conventional and emerging treatments for GCA.

Conventional Therapy: Steroids

Dr. Bhatti: What do you consider to be the best treatment strategy for GCA?

Dr. Frohman: If a patient presents with acute GCA involving visual loss or other visual symptoms, I would treat with intravenous (IV) methylprednisolone at a dosage of 1 g/day, regardless of whether the patient also has systemic signs and laboratory findings, such as an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) above 100 mm/hour.

If a patient presents several months after having experienced acute symptoms and visual loss and has ongoing systemic symptoms or positive findings from lab tests or fluorescein angiography, I would also recommend 1 g/day of methylprednisolone. For a patient with remote visual symptoms and without systemic signs at presentation, I would consider treating with approximately 1 mg/kg of oral prednisone daily.

Dr. Nesher: We would administer high-dose IV steroid therapy, 1 g of methylprednisolone daily for 3 consecutive days, to patients with acute visual loss, amaurosis fugax, diplopia, or ischemic manifestations, such as stroke or transient ischemic attack. We then continue with oral prednisone. For patients who are at 70 years or older, or patients who have comorbidities (such as diabetes or hypertension), we may give a lower dosage of methylprednisolone, such as 500 mg or 250 mg daily. We also would monitor these patients closely. The lower dosage may help us avoid side effects, including hypokalemia, arrhythmia, and acute elevation of blood pressure or blood glucose. In patients without visual or neurological ischemic manifestations, we start treatment with oral prednisone, 60 mg/day.

Dr. Bhatti: At Duke we follow a similar protocol, instituting IV steroids, usually at a dosage of 1 g/day for 3 to 5 days. I recall several years ago, I treated a patient with 2 g/day of methylprednisolone, and she ended up with cardiac arrhythmia that required telemetry monitoring. This highlights the point that patients should be monitored very carefully when given such high doses of systemic steroids.

Importance of Early Treatment

Dr. Bhatti: For a patient with GCA who has lost vision in 1 eye, what are the chances of recovering vision in that eye or of losing vision in the other eye?

Dr. Frohman: If the patient doesn’t receive treatment with IV steroids, the chance of impending visual loss in the preserved eye is approximately 40%. With swift treatment, most patients with GCA will not lose vision in the preserved eye, but vision in the affected eye is unlikely to recover. However, even with treatment, some patients will experience further visual loss.

Discharge and Tapering Regimens

Dr. Bhatti: What steroid and at what dose do you prescribe at discharge, and what is your protocol for follow-up?

Dr. Nesher: We prescribe oral prednisone, usually 60 mg/day for at least 2 weeks. If the patient had symptoms of ischemia initially, we would extend this dose of prednisone to 4 weeks. We wouldn’t expect full recovery of lost vision, but some recovery is possible. Likewise, in cases of stroke, we don’t anticipate any significant improvement. During treatment with prednisone, headache, fever, and polymyalgia rheumatica should resolve. In addition, acute-phase reactants should normalize, as evidenced by improved results of ESR and C-reactive protein tests.

We then would taper prednisone by 10 mg every 2 weeks to 30 mg/day, then by 5 mg every 2 weeks to 15 mg/day, and then by 1 mg every 2 weeks until the medication could be discontinued. We try to taper the dose to 10 mg/day or less by 6 months, and to 5 mg/day or less by 1 year. We adjust the dose and duration of treatment to the needs of each patient, but we know that relapses may occur, and we may need to increase the dose at times. The average duration of treatment is 2 to 3 years.

Supplemental Treatments

Dr. Bhatti: What medications do you recommend in addition to steroids for patients with acute visual loss?

Dr. Frohman: I routinely give antiplatelet drugs to patients with GCA. On the day of visual loss or the day after, oxygen delivery is crucial. You should make sure that the patient’s blood pressure is not low and provide supplemental oxygen. A patient with progressive visual loss should be placed in the Trendelenburg position and may require full anticoagulation therapy.

Dr. Nesher: In Israel, we routinely give aspirin at a dosage of 100 mg/day. An 81-mg aspirin tablet per day would be comparable.

Dr. Bhatti: Several studies have demonstrated the presence of varicella zoster virus (VZV) within temporal artery biopsy specimens.1 Do you think there is enough evidence to give antiviral treatment to some patients with GCA?

Dr. Nesher: Most of those data were presented by one group of researchers and have not been replicated. In studies presented at the 2016 American College of Rheumatology meeting, VZV was not detected in temporal artery biopsy specimens of patients with temporal arteritis. Also, there have been suggestions of other viral or bacterial presence in the vessel wall in GCA, but these also have not been proven. Therefore, I wouldn’t recommend any antiviral treatment for GCA at this time.

Steroid-Sparing Agents

Dr. Bhatti: What are your thoughts on steroid-sparing agents?

Dr. Nesher: Methotrexate at a dosage of 10 to 15 mg, given once per week, can modestly reduce the relapse rate and the required cumulative dose of prednisone. Methotrexate may be considered for patients with refractory or relapsing GCA or for those at risk of steroid-related side effects because of osteoporosis or uncontrolled diabetes.

Monoclonal antibodies are steroid-sparing agents with some efficacy in GCA. Anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agents were tried first but proven to be ineffective in patients with GCA.

Ustekinumab is an anti–interleukin (IL)-12 and anti–IL-23 monoclonal antibody that was evaluated in combination with prednisone in 25 patients with refractory GCA.2 For these patients, the median daily dosage of prednisone was reduced from 15 mg to 5 mg, and no patient experienced relapse of GCA while being treated with ustekinumab.

Tocilizumab, an IL-6 receptor antagonist, was found to be beneficial in several case studies of GCA. In recent months, there have been multiple randomized prospective studies of tocilizumab in patients with GCA. In a study from Switzerland, 20 patients who received tocilizumab for 1 year in combination with prednisolone were compared with 10 patients who received placebo plus steroids.3 Patients treated with tocilizumab were able to discontinue steroids 12 weeks earlier than were those in the placebo group. However, in a subsequent, follow-up study of the same patients, 11 of the 20 patients who responded to combination treatment with tocilizumab and steroids experienced relapse, which occurred 5 months (on average) after thetocilizumab was discontinued.4 In a multicenter study of 251 patients, more than 50% of those who received tocilizumab and prednisone had sustained remission at 1 year, compared with approximately 20% of patients who were on prednisone only.5 Although results are promising, monoclonal antibodies are very expensive; 1 year of treatment can cost more than $10,000. Steroid therapy is very inexpensive in comparison.

Dr. Frohman: In May, tocilizumab was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for treatment of GCA, but the appropriate duration of therapy is unclear. We may need to extrapolate results obtained by rheumatologists to determine whether we should give tocilizumab in combination with steroids to all patients with acute GCA.

Emerging Treatments

Dr. Bhatti: What do you think will be the future of GCA treatment?

Dr. Frohman: I expect that the pathophysiology of GCA will be defined further, leading to the development of appropriate high-specificity monoclonal antibodies. Hopefully, these treatments will be affordable and will be better tolerated than broad-spectrum steroids are.

As our population ages, we will see GCA more frequently. In a study of residents of Olmsted County, Minnesota, the incidence of GCA was evaluated from 1950 to 1991.6 That region of Minnesota includes many individuals of Scandinavian descent, for whom the risk of GCA is relatively high. The study found that 1% of all patients aged 80 or older had temporal arteritis.

Dr. Nesher: My assumption is that steroids will remain the core treatment of GCA, at least in the initial phase of disease. However, steroids probably will be supplemented with immunosuppressive steroid-sparing therapies, from the monoclonal antibodies we’ve mentioned to new ones, as the pathophysiology of GCA continues to be elucidated.

___________________________

1 Gilden D, Nagel MA. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2016;29(3):275-279.

2 Conway R et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68(suppl 10) [abstract 876].

3 Villiger PM et al. Lancet. 2016;387(10031):1921-1927.

4 Adler S et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68(suppl 10) [abstract 867].

5 Stone JH et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68(suppl 10) [abstract 911].

6 Salvarani C et al. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123(3):192-194.

___________________________

Dr. Bhatti is chief of the neuro-ophthalmology division at Duke Eye Center and professor of ophthalmology, neurology, and neurosurgery at Duke University Medical Center in Durham, N.C. Relevant financial disclosures: Novartis Pharmaceuticals: C,L; Receptos: C.

Dr. Frohman is vice chair of ophthalmology and professor and director of neuro-ophthalmology at Rutgers–New Jersey Medical School in Newark. Relevant financial disclosures: Quark Pharmaceuticals: S.

Dr. Nesher is a rheumatologist and head of the internal medicine department at Shaare-Zedek Medical Center and associate clinical professor at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. Relevant financial disclosures: None.

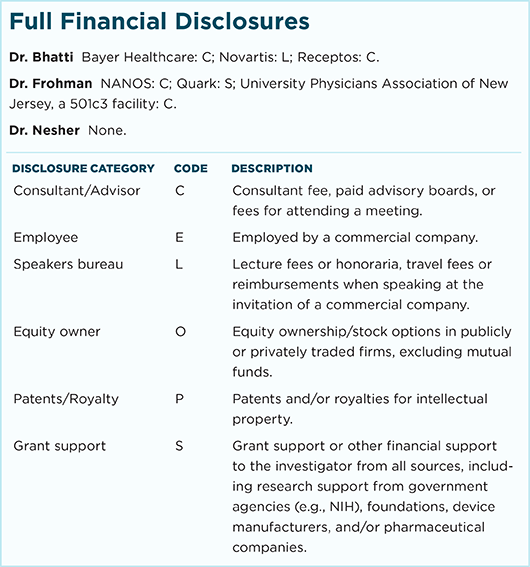

For full disclosures and the disclosure key, see below.