This article is from April 2006 and may contain outdated material.

The Department of Veterans Affairs is investing in ophthalmology and providing ophthalmologists with opportunities for leadership in patient care, technology, research and teaching. And without the administrative hassles of private practice, the VA’s ophthalmologists can focus on delivering high-quality patient care.

With sawdust and building supplies littering the hallways of the third floor ophthalmology wing of the Philadelphia Veterans Hospital, it looked like the team from “Extreme Makeover Home Edition” was working its wonders in a most unlikely place. Workmen in overalls bent over rotary saws as movers carried a brand-new Haag-Streit slit lamp, an IOL Master and a visual field machine into some of the newly painted rooms. A parade featuring a new Zeiss OR microscope, a new phacoemulsification machine and a new digital recording system snaked up the corridor toward the operating rooms. But spiked-haired TV star Ty Pennington was nowhere to be found because this isn’t about mere home improvement; it is about something far more important—ensuring the nation’s veterans receive superior quality eye care.

Improving Patient Care

All that construction activity during the winter of 2005–2006 was part of the Philly VA’s efforts to expand its ophthalmology services by increasing the number of exam lanes from nine to 17. A spacious new waiting room, administrative offices and laser suite were built to serve the increasingly heavy load of eye patients seen by Michael E. Sulewski, MD, chief of ophthalmology at the Philadelphia VA Medical Center, and his team of ophthalmology residents, fellows, part-time ophthalmologists and optometrists, the ranks of whom were also being increased to help shoulder the load. “Ophthalmology is really high on the priority list within this hospital,” said Dr. Sulewski, who, like many other top-flight VA ophthalmologists, also holds a university-affiliated appointment as codirector of the cornea service and chief of refractive surgery at the Scheie Eye Institute of the University of Pennsylvania.

In years and decades gone by, VA hospitals around the country, faced with pressing patient loads and besieged budgets, might have forgone the expense of dramatically refurbishing an ophthalmology service, no matter what the patient demand. But this isn’t your father’s VA. Things have changed, and for no subspecialty more so than ophthalmology. “The VA front office has always supported me 100 percent,” said Dr. Sulewski. “Our objective is to provide eye care at the VA that is second-to-none and makes no distinction between the care provided to our nation’s war heroes and that provided at the prestigious neighboring university hospital.”

Actually, Dr. Sulewski, a well-respected cornea, cataract and refractive surgery specialist who has repeatedly been selected to teach cataract surgery to residents at a two-week summer course at Harvard, and who is typical of the new breed of ophthalmologists at the VA, may be understating the VA’s efforts to keep pace with high-quality, private sector ophthalmology. In some cases, the VA is going way beyond the eye care that private health care systems are offering.

The VA Goes High-Tech

Nowhere is that clearer than the VA’s drive into teleretinal imaging. Right now, the VA is in the midst of a pioneering rollout that will see 18 of the VA’s 21 Veterans Integrated Service Networks—the regional groups into which the VA is divided—deploy up to six nonmydriatic Topcon cameras each at primary care sites throughout their service area. The goal, of course, is to screen veterans for diabetic retinopathy when they come in for regular check-ups or diabetes care, as opposed to when they come in specifically for eye care. About 20 percent of veterans seen at VA facilities have diabetes.

Mary G. Lawrence, MD, associate chief of ophthalmology at the Minnesota VA since 1998, who is also associate professor of ophthalmology at the University of Minnesota, is as responsible as anyone for the VA’s leading-edge efforts here.

It was Dr. Lawrence who ran the initial demonstration project a few years back that showed the value of teleretinal imaging within the VA. But Dr. Lawrence did more than simply demonstrate teleretinal imaging could work. The Joslin Vision Network in Boston, which is associated with Harvard, had already proven that stereoimaging was effective. Dr. Lawrence was able to show the worth of an alternative non-stereoimaging program, where three photos of each retina, instead of the six stereo shots prescribed by Joslin, showed extremely good sensitivity, and at a price the VA could afford.

She placed a Topcon camera in a VA primary care setting in North Dakota, where optometrists doing traditional face-to-face eye exams were having difficulty keeping up with demand. Prior to that, some diabetic veterans had to drive the 250 miles to the Minneapolis VA to get their diabetic retinal exams done. A significant percentage declined to do so. So Dr. Lawrence put a camera in the North Dakota primary care clinic and dispatched Gary S. Michalec, CRA, the ophthalmic photographer at the Minneapolis VA, to train a licensed practical nurse to image the diabetic patients’ retinas. Those images were then sent in “store and forward format” to a reading center at the Minneapolis VA, and read by ophthalmologists. After the first year of implementation, the percentage of diabetics screened at the Dakota clinic for diabetic retinopathy jumped from 47 percent to 72 percent. Dr. Lawrence now has four remote imaging centers up and running, and her reading center has read images from about 10,000 patient visits. “Our system is efficient and effective, using off-the-shelf technology that makes it possible for a veteran with poor access to eye care to be checked for diabetic retinopathy,” said Dr. Lawrence.

“Contrary to what one might think of government organizations, the VA encourages innovation. My own experience shows that one can step into a leadership role in promoting positive change for patients,” said Dr. Lawrence.

About the VA’s Improvements

James C. Orcutt, MD, the VA’s top ophthalmologist, says the VA’s transformation into a cutting-edge health care system has been under way for a decade. Dr. Orcutt has been at the VA for 23 years. Besides his national administrative duties, he serves as executive director, surgical and perioperative care at the VA Puget Sound Health Care System in Seattle, and also practices at the American Lake VA in Tacoma. “Twenty years ago, the VA did not have a very positive image,” he said. “But that has really changed.” As evidence, Dr. Orcutt refers to an Annals of Internal Medicine article,1 which showed that a higher percentage of diabetics visiting the VA in any recent year received an eye care exam than did diabetics who received care through commercial managed care organizations.

More ophthalmologists needed. Those exams are frequently performed by any of the about 230 full-time employee equivalent (FTEE) ophthalmologists the VA employs. About 60 are full-time. Some work 5/8th of their time at the VA, while others come in for half a day a week, and still others work hours somewhere in between. That total is up from about 173 FTEE ophthalmologists in the early 1990s, according to Dr. Orcutt.

Those numbers are rising—Dr. Orcutt said the VA is always looking for ophthalmologists—because of the crushing numbers of vets needing eye care. “One year ago, we looked locally at the numbers and types of consultations originating in primary care clinics,” reported Dr. Orcutt. “Number two was for eye care.” Out of a total of 4.5 to 5 million veterans visiting VA facilities in fiscal year 2005, 1.28 million—or about one-quarter—came in for eye care, and they accounted for a total of 2.14 million visits in fiscal year 2005. Those visits are spread out across the 130 VA eye clinics located around the United States, not all of which are staffed by ophthalmologists.

Given this skyrocketing demand for eye care (up 95 percent between 1996 and 2005), the VA’s desire to bring on more ophthalmologists makes good fiscal sense. Mary Gerard Lynch, MD, chief of ophthalmology at the Atlanta VA Medical Center, believes that workload data from within the VA Healthcare System supports the notion that ophthalmology provides the most cost-effective eye care to veterans. A national survey from 2002 and a second, regional survey from 2005 compared the efficiency of the three tertiary eye care delivery models within the VA—ophthalmology service alone; ophthalmology and optometry working independently; and the two working jointly within the same clinical space. In both surveys, a tertiary eye clinic relying on ophthalmology alone cared for, on average, nearly twice as many patients per provider compared with clinics utilizing ophthalmology and optometry.2,3 Another VA survey showed that a VA ophthalmologist’s productivity increased by 30 percent when assisted by a trained eye care technician (compared with an optometrist’s productivity, which rose only 16 percent).4

The Association of VA Ophthalmologists is now working to develop an Eye Care Technician Series for the VA to provide even better care for veterans. “Our veteran population is both growing and aging at a very rapid rate. Since eye care is very complex and technology-driven, we must find the most cost-effective way to provide excellent care to our patients. They deserve the best we have to offer them. Regarding eye care, that may well mean an ophthalmology-directed service utilizing highly skilled technicians. The VA is in a unique position to look at the process of eye care delivery since it has been collecting data consistently for the past 12 years,” Dr. Lynch said.

Research Opportunities

The VA is active in clinical research as well. Jiong Yan, MD, director of vitreoretinal services at the Atlanta VA and assistant professor of ophthalmology at Emory University, is an investigator in the phase 2 study for the subretinal chip implant by Optobionics. She and Thomas M. Aaberg Sr., MD, chairman of ophthalmology at Emory, implanted the retinal prosthetic in seven retinitis pigmentosa patients in a collaborative effort between the VA and Emory—with the VA recruiting and screening the patients and providing vision testing and Emory providing surgical care. Without the VA’s low vision rehabilitation research and development center in Atlanta and its unique ability to perform the pre- and postoperative vision testing, she said, the Emory University surgeons would not have been able to participate in this research. “This is one of the first clinical trials of a surgical implant that gives hope to those who, prior to this, had little chance of seeing again, and I’m fortunate to have had an opportunity to be part of this study,” said Dr. Yan.

Dr. Yan’s principal investigator in the Optobionics trial is Ronald A. Schuchard, PhD, director of the Atlanta VA Rehabilitation Research and Development Center. At the center, Dr. Schuchard has clinical fellows and young faculty who are funded by the VA’s Research Career Development (RCD) program, but none are ophthalmologists. “I’d love to have an ophthalmologist!” he said. The program supports young clinicians who would like to pursue research. The awards pay the physicians’ salary for three years with the stipulation that 75 percent of their time be spent on research of their choosing (which must be conducted with a VA facility) and the rest in their clinical practice. (To learn more about the award, visit www1.va.gov/resdev/funding/cdp.cfm.) “The VA has medical, rehabilitation and health services RCD programs that provide a wide range of research opportunities for ophthalmologists who want to have dedicated time to develop a research program,” he said.

Teaching and Learning

Most ophthalmologists work out of secondary and tertiary VA facilities like the Philadelphia VA where, as attendings, they have a chance to work with ophthalmology residents like Gil Binenbaum, MD, a resident at the Philly VA. As a resident at the Scheie Eye Institute, Dr. Binenbaum has rotated through the VA three times over three years, each time for 10 weeks. “Having a VA rotation is an outstanding educational experience for residents,” Dr. Binenbaum said.

And H. Dunbar Hoskins Jr., MD, executive vice president of the Academy, said this experience benefits not only residents, but also the profession as a whole. “More than half of ophthalmologists spend part of their training at the VA, making it critical to the quality of eye care in the United States,” he said.

Besides learning from Dr. Sulewski, Dr. Binenbaum also benefits from the supervision of Nicholas J. Volpe, MD, director of the ophthalmology residency program at Scheie, who has worked as an attending at the Philly VA since 1993. “The VA is the best-equipped facility I work in,” said Dr. Volpe. But he highlights another important VA benefit for an ambitious ophthalmologist: the professional challenges. “The ophthalmologist out in private practice is shaking the trees trying to get healthy people to come in,” Dr. Volpe explained. “Healthy people can be routine and do not present the same challenges medically and surgically as patients with significant eye disease.”

“Most patients coming in to the VA have something wrong with them,” Dr. Volpe continued. “Many vets tend to minimize their symptoms. So when they come in, something is often very wrong. They are not just coming in for a free pair of eyeglasses.”

And Other Benefits

Dr. Volpe also enjoys the no-hassle environment for ophthalmologists—and other physicians—at the VA, a benefit mentioned also by Randy L. Johnston, MD, the Academy’s senior secretary for advocacy, who ran the retina clinic at the VA in Cheyenne, Wyoming, part-time until a few years ago. “I didn’t give up the clinic voluntarily,” Dr. Johnston said ruefully. “They decided to get a full-time ophthalmologist on the premises.”

At the VA, there were none of the headaches he faces in private practice. It is bad enough that his malpractice insurance premiums are rising 15 percent to 20 percent a year, even though there has never been a malpractice claim against an ophthalmologist in Wyoming. He is also knee-deep in paperwork from the multiple insurance companies he has to deal with. Then there is workers’ compensation. And how about capital expenditures on a new medical records system for his office, which will cost upward of $200,000. “You don’t have to worry about any of those hassles when you practice at the VA,” Dr. Johnston said.

______________________________________

For more information. If you are interested in learning about the benefits of practice at the VA, contact the human resources department at the VA Medical Center near you. To find locations, go to www.va.gov/directory and click on your state, or call the VHA Placement Service at 800-949-0002.

________________________________________________

1 Kerr, E. A. et al. Ann Intern Med 2004;141(4):272–281.

2 “VA Ophthalmology and Optometry Service Panel Size and CARES Recommendations,” November 2002.

3 “Advanced Clinic Access Collaborative Course to Reduce Waits and Delays,” 2005.

4 “Joint Ophthalmology/Optometry VA Eye Care Survey,” 1998.

|

|

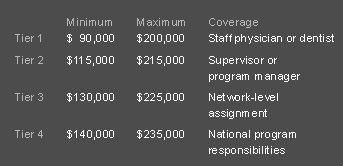

The VA's New Salary Scale. The VA's New Salary Scale. In January the VA implemented a new annual pay system, which gives facility directors more latitude in recruiting and retaining ophthalmologists. Pay at the VA is now calculated according to base pay, market pay and performance pay. The table below shows the minimums and maximums for base and market pay combined. On top of this, it’s possible to earn up to $15,000 in performance pay, when specific goals are met. “We are pleased to see VA attempt to improve its recruitment flexibility,” said Dr. Hoskins.

|