This article is from April 2012 and may contain outdated material.

Since the United States adopted universal childhood vaccination against chickenpox (varicella) in 1995, the incidence of that formerly common childhood disease has fallen precipitously. Although the Varivax vaccine (Merck) does not prevent all cases of chickenpox, its course is substantially milder in vaccinated children.1

Despite this good news, concerns have been raised that the dramatic decline in chickenpox may, paradoxically, increase the occurrence in older adults of its potentially more severe sequel, herpes zoster (HZ), commonly known as shingles.

The elimination or substantial reduction of chickenpox will ultimately lead to a corresponding decrease in shingles, which can only occur in someone who has had chickenpox. But for the next few decades, the opposite phenomenon may be present: Less chickenpox may mean more shingles—and its potentially sight-threatening ocular manifestation, herpes zoster ophthalmicus (HZO). Three experts unravel the paradox and discuss how best to manage HZO in the meantime.

Interplay of Chickenpox and HZ

According to Thomas J. Liesegang, MD, professor of ophthalmology at Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, Fla., while it’s clear that Varivax has led to a dramatic decrease in morbidity and mortality from chickenpox, “The question is whether in avoiding chickenpox we’re increasing the risk of HZ in the elderly.” He added that HZ is associated with more deaths, and is much more costly to treat, than chickenpox.

Overview of HZ etiology. Understanding this conundrum requires a brief overview of the etiology of HZ. Both chickenpox and shingles are caused by the varicella-zoster virus (VZV). After the acute disease of chickenpox resolves, VZV resides indefinitely in the individual’s sensory ganglion tissues. Thus, anyone who has ever had chickenpox—even without being aware of it, in subclinical cases—has a lifelong liability to later reactivation of the virus in the form of HZ; approximately 1 million such cases of shingles occur annually in the United States.1

In contrast, children who are vaccinated receive an attenuated form of the virus and have a smaller viral load than if they had contracted chickenpox. As a result, they are less likely to experience systemic viremia, seeding of the ganglia and reactivation.

Immune boosting is protective against HZ. The development of cell-mediated immunity to VZV from a bout of chickenpox protects people against further episodes of the disease and, as long as that immunity remains strong, against outbreak of shingles. However, reactivation of VZV may occur in the presence of immune-suppressing conditions, such as HIV infection, and the decline in immune status that occurs naturally with aging. Dr. Liesegang said that an essential factor in keeping cell-mediated immunity primed and effective is “immune boosting,” which occurs from periodic asymptomatic release of virus from the nervous system—and, even more important, from exposure to people with chickenpox. “If chickenpox is not circulating in the community, elderly people are not being exposed and are not getting their immune boosts—which means that their immunity will decline quicker, and they’ll have increased risk of HZ.”

|

|

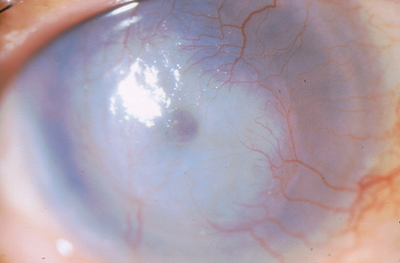

Ominous Findings. Reduced corneal sensation in HZO may contribute to corneal scarring and early melting, as seen here.

|

Is the Zoster Vaccine the Answer?

Although vaccination can serve as a substitute for the community-acquired, immune-boosting effect of exposure to people with chickenpox, the Varivax varicella vaccine was not designed for that purpose. The good news is that the newer Zostavax vaccine (Merck) was approved by the FDA in 2006 on the basis of efficacy demonstrated in the Shingles Prevention Trial, where it reduced the incidence of HZ in people 60 years and older by 51 percent, reduced the burden of disease pain and duration by 61 percent, and reduced the troubling complication of postherpetic neuralgia by 67 percent.2 More recently, the vaccine was found to be even more effective in patients aged 50 to 59, in whom it reduced the risk of shingles by 70 percent, and it is now indicated for people aged 50 and older.3 Problem solved? Not quite yet.

Vaccine adoption slow. Unlike the universal vaccination of U.S. children with Varivax, said Dr. Liesegang, Zostavax has not been well accepted by patients or physicians, despite its demonstrated safety and relative effectiveness.

Several factors come into play, he said. It is not covered by Medicare Part B and costs the patient about $200; moreover, it must be kept frozen and expires, so physicians may not wish to stock it in the office. Finally, many primary care physicians—the doctors most likely to manage patients’ vaccinations— may not consider it worthwhile. “PCPs tend to consider shingles to be merely a nuisance disease because most cases they see are mild. We ophthalmologists have a different perspective. We rarely see the simple cases; our patients come to us with the ocular complications of HZO, which can have serious consequences.”

What does this mean for Eye M.D.s? In brief, ophthalmologists can expect to see continuing, and perhaps even greater numbers of, cases of HZO for years to come—even though there are now effective vaccines for both chickenpox and HZ. In the longer term, however, as the cohorts of children who were vaccinated beginning in 1995 grow up, rates of HZ and its ocular complications should decline. Clinicians should also be aware that universal vaccination of children for chickenpox has, thus far, occurred only in the United States; thus, physicians who treat patients from or in other countries will see different epidemiologic patterns. Consequently, Eye M.D.s have an ongoing need to diagnose and treat HZO.

Diagnosis of HZO

Perhaps the simplest aspect of managing HZO is diagnosing it, usually based on a characteristic clinical picture. Imaging or laboratory studies are rarely called for.

HZO is most often associated with an obvious maculopapular rash on the face. According to Keith H. Baratz, MD, professor of ophthalmology at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., “Typically, with a full-blown case of zoster, you can make the diagnosis from across the room.” He said that the rash follows the dermatomes and “respects the midline,” appearing on only one side of the forehead, one side of the nose, and on the upper, but not usually lower, eyelid. The upper lid may sometimes have massive swelling similar to cellulitis (Fig. 2). W. Barry Lee, MD, partner in the cornea, external disease and refractive surgery service at Eye Consultants of Atlanta, added that the presence of Hutchinson’s sign—lesions on the side or tip of the nose—is a strong indicator of ocular involvement.

Comprehensive exam needed. But even though recognizing the presence of HZO is easy, uncovering all of its ocular manifestations is more complex. Although conjunctivitis is often the initial eye finding, said Dr. Baratz, keratitis, inflammatory glaucoma, uveitis, retinitis and transient muscle palsy with double vision may also develop.

Dr. Lee recommends performing a comprehensive examination on all HZO patients. “I start with the rash on the eyelids, move to the conjunctiva and cornea, check intraocular pressure (IOP) for possible glaucoma, look for inflammatory signs of uveitis, and perform a dilated fundus exam for acute retinal necrosis (ARN). I worry about the state of the corneal nerves—reduced sensation can result in corneal melting or perforation. I think that testing corneal sensation is really important, and I also look for any punctate corneal staining as an early sign of trouble.”

|

After toric IOL implantation, a surgeon can use the Toric Results Analyzer ( www.astigmatismfix.com) to determine whether going back into the eye and rotating the lens would decrease residual astigmatism. |

Treatment of HZO

Treatment of HZO begins with a seven- to 14-day course of an oral antiviral agent: acyclovir, famciclovir or valacyclovir.4 Dr. Liesegang said that all three are effective in reducing some of the signs and symptoms of HZ, although the drugs vary in cost and dosing regimens. Acyclovir, which has been available the longest, is the least expensive.

Speed is critical. Dr. Liesegang emphasized that, for maximum efficacy, treatment must be started within 72 hours of the onset of symptoms. He said that he will initiate treatment early if he even suspects HZ. “Fortunately, the therapy is safe enough that you can err on the side of treating a patient who may turn out not to have HZ.” Dr. Baratz agreed with this aggressive approach: “If you miss that initial time window, you will have missed an opportunity to make a long-term impact on the patient’s disease down the road.” In some cases, however, the primary care physician will have already begun antiviral treatment before the ophthalmologist is involved.

The role of steroids. Dr. Liesegang said that two NIH-sponsored studies5,6 prove that oral steroids, given early in the course of HZ along with the oral antivirals, reduce acute pain and lead to better quality of life and more rapid recovery. However, he added, “Many ophthalmologists do not follow the guidance of these trials because they’re afraid of the side effects of steroids in patients who may be immunosuppressed. This is one of the few instances I know in which results of well-controlled trials are thrown out by clinicians.” He noted that there are some instances in which systemic corticosteroids must be strongly considered, including patients with marked hemorrhagic rashes, proptosis with external ophthalmoplegia, optic neuritis, and contralateral hemiplegia due to cerebral angiitis, as well as various forms of retinal necrosis.

Other treatments. Most patients with HZO have a self-limited form of disease that has an acute onset but resolves within two weeks with oral antivirals and corticosteroids, Dr. Liesegang said. For the approximately 30 percent who have more severe, ongoing HZO, a variety of other therapies may be appropriate, including topical medications and surgery, depending on the individual patient’s needs. According to Dr. Baratz, “There are so many possible conditions. You treat what you see.” He considers keratitis, glaucoma and ARN to have the greatest sight-threatening potential.

Keratitis. In cases of neurotrophic keratitis, Dr. Baratz suggests protecting the ocular surface with topical steroids, lubricants and bandage contact lenses. Dr. Lee added that the most ominous results of keratitis are corneal melting and perforation. He is sometimes able to manage small holes with a corneal glue patch.

With larger perforations, corneal transplants may be needed, but results may be poor because of impaired corneal sensitivity, said Dr. Lee. His treatment of choice with HZO-associated corneal perforation is a transplant plus tasorrhaphy to protect the cornea and promote healing.

Glaucoma. Intraocular inflammation can affect the trabecular meshwork and lead to inflammatory glaucoma. This condition can often be treated with IOP-lowering medications and steroids, said Dr. Baratz, adding that “a challenge arises when a patient has steroid-induced glaucoma superimposed on keratitis or uveitis requiring steroid treatment.” This group often needs glaucoma surgery.

Acute retinal necrosis. This serious condition often leads to retinal detachment and should be referred to a retina specialist, said Dr. Lee. He added that surgery with vitrectomy and scleral buckle are generally the initial treatments. “But results are mixed, and later treatment typically uses silicone oil in the posterior segment to hold the retina in place.”

Chronic or smoldering disease. Dr. Liesegang said that, despite appropriate treatment, “Some individuals, for unknown reasons, go on to develop chronic disease, which is frustrating for the physician and patient. You can try to control the inflammation and pain, but there’s sometimes permanent damage and ongoing pain.” He said that the clinician can attempt to manage the symptoms empirically; referral to a pain specialist may be needed for postherpetic neuralgia.

Dr. Baratz said that HZO can seem to “drag on forever,” with a waxing and waning course. He said that ophthalmologists should remain vigilant for late sequelae and be cautious about discontinuing therapy: “I saw a patient who had been on topical steroids for 10 years after onset, and she was doing great. She figured that, 10 years later, it was OK to stop medication. But after stopping, she developed keratitis and had profound visual loss.”

Dr. Baratz emphasized—and the other experts agreed—that HZO is a complex disease, not to be taken lightly.

___________________________

1 Liesegang TJ. Can J Ophthalmol. 2009;44(4):379-384.

2 Oxman MW; Shingles Prevention Study Group. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(22):2271-2284.

3 Voelker R. JAMA. 2011;305(15):1526.

4 Lee WB, Liesegang TL. Herpes zoster keratitis. In: Krachmer J et al. Cornea. 3rd ed. New York: Elsevier; 2011, chap. 80.

5 Whitley RJ et al. Ann Intern Med. 1996;125(5):376-383.

6 Wood MJ et al. N Engl J Med. 1994;330(13):896-900.

___________________________

Drs. Baratz and Liesegang report no related financial disclosures. Dr. Lee is on the speakers bureau for Allergan and Bausch + Lomb.