Download PDF

Though Ebola virus disease (EVD) killed more than 11,000 people in western Africa in 2014-2015, thousands of others survived the infection. And survivors are at high risk for developing vision loss from uveitis in the months after their recovery from acute disease, researchers have concluded.

Wide range of ocular findings. Ophthalmic examinations of 96 Ebola survivors who had sought help for vision problems at a specially established clinic in Monrovia, Liberia, showed that 21 patients (22%) had uveitis (26 affected eyes), and 3 patients (4 eyes) had optic neuropathy.1 The researchers noted that their report was the first detailed characterization of an EVD-associated uveitis phenotype and its association with impaired visual acuity.

|

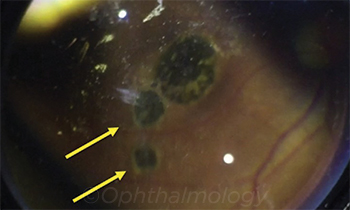

EVD UVEITIS. Fundus photo using a 28-diopter condensing lens and an iPhone shows chorioretinal scarring with characteristic hyperpigmented scars with hypopigmented halo (yellow arrows) in an EVD survivor with posterior uveitis. Similar lesions were observed in the retinal periphery.

|

“The wide spectrum of findings was really interesting, in that patients ranged from [having] anterior uveitis to panuveitis. In addition, optic neuropathy was observed. We also saw patients who had chorioretinal scarring, sometimes within the macula, unfortunately,” said coauthor Jessica Shantha, MD, fellow in uveitis at the F.I. Proctor Foundation, University of California, San Francisco. “Nearly 40% of patients who developed eye disease had severe vision impairment by World Health Organization criteria—that is, 20/400 or worse vision.”

Dr. Shantha and Emory University uveitis specialist Steven Yeh, MD, were among the visiting physicians who responded to reports of ocular problems among Ebola survivors by helping to establish an eye clinic at the Eternal Love Winning Africa (ELWA) Hospital in Monrovia.

Clinical exams of the 96 patients during the clinic’s first month of operation showed the following:

- Symptoms. Blurry vision and photophobia were the most common symptoms, found in 76% and 68% of clinic patients, respectively. Other common symptoms were tearing (62%), pain (56%), floaters (47%), and redness (43%).

- Eye conditions. Among those presenting to the clinic, 35 (36.5%) had apparently normal ocular exams. In addition, a number of patients were found to have non–EVD-associated eye disease, including cataract, refractive error, dry eye, glaucoma, and retinal detachment.

- Visual acuity (VA). Eyes with EVD-associated uveitis had significantly worse vision than did those without uveitis. Of the eyes with uveitis, 38.5% were blind (defined as VA 20/400 or worse). However, 54% of uveitic eyes had VA of 20/70 or better.

- Uveitis subtypes. Posterior uveitis was the most common form (57%), followed by panuveitis (29%). Active Ebola virus was found in 6 eyes, all of which had been diagnosed with panuveitis.

- Exam findings. Eyes with uveitis were significantly more likely than those without uveitis to have anterior chamber cells (p = .01), keratic precipitates (p = .01), posterior synechiae (p < .001), and chorioretinal scars (p < .001).

Caring for survivors. Overall, the study demonstrates the importance of ophthalmic care for patients who contract Ebola, said Dr. Yeh, who is the M. Louise Simpson Associate Professor of Ophthalmology at Emory University. “Ebola survivors should be evaluated, at the very least, shortly after they leave the Ebola Treatment Unit setting,” he said.

However, because ophthalmic care is scarce in the countries of western Africa, he and other visiting ophthalmologists have been teaching health care workers to perform screening exams, he said. “Eye care nurses trained in the slit-lamp examination are also very capable of evaluating patients for uveitis,” he said.

Theories of Ebola eye disease. Many mysteries remain about when and how Ebola affects the eye, Dr. Yeh said. For instance, an earlier study in Sierra Leone found an association between uveitis and 2 factors observed in the disease’s acute phase: a greater concentration of Ebola virus in patients’ blood samples, and red/injected eyes at the time of diagnosis.2

“One hypothesis is that a higher viral load enables Ebola to enter the eye, establish viral persistence, and later lead to uveitis. Red/injected eyes could be a sign of conjunctival hyperemia or subconjunctival hemorrhage, which is frequently seen as a manifestation of acute EVD. Alternatively, red/injected eyes could also be a sign of acute uveitis at the time of EVD diagnosis. However, this link requires further study,” Dr. Yeh said.

—Linda Roach

___________________________

1 Shantha JG et al. Ophthalmology. 2017;124(2):170-177.

2 Mattia JG et al. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16(3):331-338.

___________________________

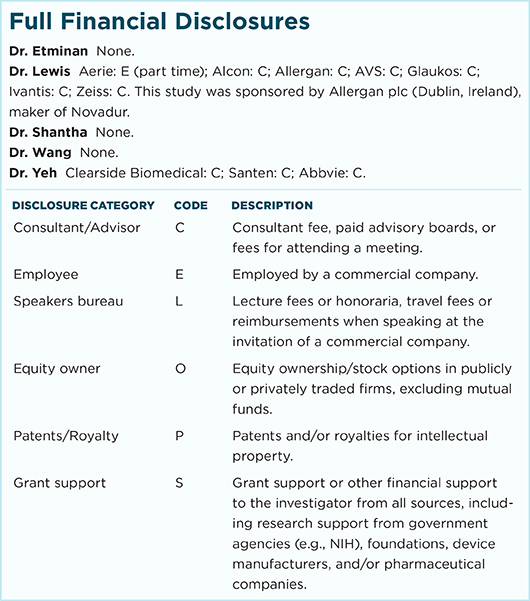

Relevant financial disclosures—Dr. Shantha: None. Dr. Yeh: None.

For full disclosures and disclosure key, see below.

More from this month’s News in Review