By Annie Stuart, Contributing Writer, interviewing Lisa S. Schocket, MD, Jay Stewart, MD, and Rahul S. Tonk, MD, MBA

Download PDF

As vitreoretinal surgeons know all too well, a surprise can arise anytime during or after surgery—and it may be a substantial one.

“A case that really hit home for me was a diabetic gentleman who’d had a retinal detachment repaired elsewhere,” said Lisa S. Schocket, MD, at the University of Maryland in Baltimore. “As far as I could tell, the prior surgeon had done a good job fixing the retina, but the cornea had completely failed and the patient’s vision in one eye was light perception only.” When Dr. Schocket attempted to fix a retinal detachment in the other eye, the entire epithelium sloughed off, even though she hadn’t touched the cornea—let alone scraped it for better visualization of the retina.

What went wrong? Although the retina was free of retinopathy, diabetes had devastated this patient’s cornea and his vision. It’s a cautionary tale for vitreoretinal surgeons: You must also pay attention to the condition of the cornea to ensure an overall positive outcome.

|

|

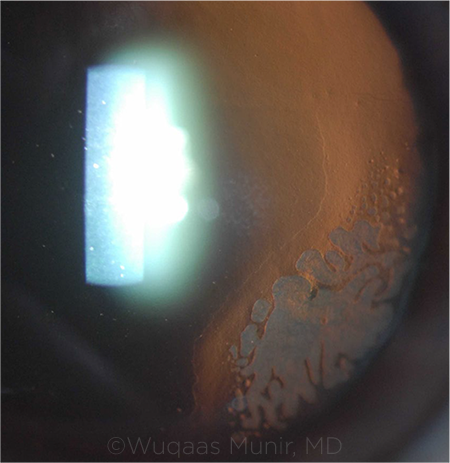

COMPLICATION. Use care when repositioning a dislocated LASIK flap in order to avoid epithelial ingrowth, pictured above.

|

Remembering Risks to the Cornea

Rahul S. Tonk, MD, MBA, is at the Bascom Palmer Eye Institute in Miami. He repeatedly sees corneal problems following vitreoretinal surgery—from infections to neurotrophic keratitis and epithelial defects. An important step for surgeons, he said, is to simply be aware of patients who are at increased risk.

Diabetes. Vitreoretinal surgery is safer for diabetic patients than it used to be, leading to fewer corneal and anterior segment complications than 20 years ago, said Jay Stewart, MD, at UCSF Health in San Francisco. “Small-gauge instrumentation with less dissection of the ocular surface makes surgery safer, creating less post-op vascularization and irritation at the ocular surface.”

However, he said, patients with diabetes have compromised nerves and blood flow, which can underlie some of the complications that may arise, such as abnormal vascularization or nonhealing corneal epithelial defects. Dr. Schocket added, “Before going into the OR, be sure to take a thorough history.”

Aphakia. In aphakic patients, vitreoretinal surgery causes more turbulence of irrigation fluid flow at the corneal endothelium, said Dr. Stewart, who suggested application of a viscoelastic agent in the anterior chamber for protection.

Recent incisions. Dr. Stewart also suggests being mindful of corneal incisions from prior cataract or other anterior segment surgeries. “If the surgery was recently performed, incisions could be unstable,” he said. “To avoid leakage through those incisions, it may be advisable to place sutures through the incisions prior to placement of the vitrectomy trocars.”

Prior refractive surgery. A LASIK flap wound never heals completely, said Dr. Schocket, who’s experienced a dislocation twice. In fact, studies have shown that the strength of the healed wound margin is on average only 28% of the normal cornea.1 This can lead to flap dislocation during retina surgery. “I’ve learned to specifically ask patients multiple times whether they’ve had LASIK, not just eye surgery,” she said, “because many don’t think of it as a surgical procedure.” (See “Dislocation of a LASIK Flap,” below.)

Dislocation of a LASIK Flap

If you’re not aware that a patient has a LASIK flap, you may inadvertently do things during retina surgery to destabilize it, said Dr. Schocket. “For example, if you’re placing viscoelastic jelly on the surface of the cornea and the wound is not perfectly sealed, the material can slowly ooze under the flap and loosen it.” The view to the retina then becomes unclear, she said. Not realizing that this is due to a flap dislocation, the lead surgeon may scrape the cornea, which completes the displacement of the flap.

Here’s how to avoid a LASIK flap dislocation.

Avoid a buckle. “I’ve only seen a dislocation happen with a buckle,” said Dr. Schocket. “It’s not always possible, but it’s best to try to avoid a buckle in patients with prior LASIK. During a buckle, viscoelastic material can potentially seep under the flap and lift it off.”

If you must scrape. “If you need to scrape, do it carefully, starting from the corneal apex and scraping toward the limbus,” said Dr. Tonk. “If you scrape from the limbus uphill toward the corneal apex, your blade may get underneath the LASIK flap, and you may inadvertently lift it.”

If dislocation occurs. Proper repositioning of the LASIK flap is critical to avoid striae, irregular astigmatism, and epithelial ingrowth within the flap interface. In addition, these eyes must be watched carefully for diffuse lamellar keratitis postoperatively.

Rinse the surface and interface thoroughly with BSS to wash away any released epithelial cells and prevent epithelial ingrowth, said Dr. Schocket. Then carefully reposition the flap, before completing the vitrectomy, which may be more challenging now due to multiple interfaces.

If the flap does not reposition smoothly into the stromal bed, Dr. Tonk advises the following:

- Remove the epithelium from over the top of the flap to reduce “bunching.”

- Use hypotonic saline or sterile water to swell and stretch out the flap.

- If all else fails, secure the flap with four to six sutures, but remove them within a few months to avoid inducing irregular astigmatism.

STRIAE. Dislocated LASIK flap? Avoid striae with proper repositioning.

|

When Neurotrophic Keratitis Occurs

A degenerative disease characterized by decreased corneal sensitivity and poor corneal healing, neurotrophic keratitis (NK) makes the cornea susceptible to injury.

Because surgery can trigger or exacerbate NK, it’s important for vitreoretinal surgeons to discern which oftheir patients already have it or to anticipate which patients may be predisposed to NK, said Dr. Tonk. Patients at greatest risk may include those with diabetes, as well as those—with or without diabetes—who will undergo heavy endolaser photocoagulation for complex retinal detachments. In the latter scenario, “the heavier or more confluent the laser, the greater the risk of damage to the sensory long ciliary nerves,” he said.

As you look for NK, it’s important to note that it has several stages.

Stage 1 NK may simply look like severe dry eye, said Dr. Tonk, except that it doesn’t often respond to lubricant drops alone. “Clues that you are dealing with NK include a diffuse pattern of punctate keratopathy and a swollen, irregular epithelium, all of which can be responsible for several lines of decreased vision.”

Stage 2 NK is associated with recurrent or persistent epithelial defects or delayed healing following epithelial scraping, said Dr. Tonk. These defects are often bordered by rolled, loose edges of swollen epithelium.

Stage 3 NK is characterized by a corneal ulcer wherein the stroma may melt or even perforate. Surgeons should investigate for melt when looking at any epithelial defect, said Dr. Tonk. This can be done easily with a thin, high-powered slit beam or by obtaining an anterior segment optical coherence tomography scan. Even in the best case, melts are associated with corneal haze and irregular astigmatism and can limit final visual outcome.

Posterior Dislocation of a DSAEK Graft

In very rare cases, a corneal transplant can drop into the posterior pole. Dr. Stewart coauthored a case series about this several years ago.1

“I think the message got through,” he said. “Many corneal surgeons have now begun to suture the DSAEK graft in cases where the patient is aphakic or where there is a lot of zonular loss. It serves as a leash to keep the cornea in the anterior chamber while placing the graft. They also may place stay sutures to help hold the cornea in place.”

Immediate removal. “If a dislocation occurs, we recommend removal from the posterior segment within 24 hours because proliferative vitreoretinopathy [PVR] can set in quickly,” said Dr. Stewart. And contraction of scar tissue can cause a retinal detachment, added Dr. Schocket.

How to remove the graft. The most reliable way to remove the graft is with a 23-gauge vitrectomy, said Dr. Stewart. The instrument has a large mouth at its tip, making it easier to engage the corneal tissue for removal. “After the vitrectomy is performed, the cut rate can be lowered to approximately 500 cuts per minute to facilitate the removal of more dense material such as the corneal graft,” he said. “That allows the vitrector to take a larger bite and make removal more efficient.”

For adherent tissue. Usually, you can easily remove most of the corneal tissue from the retinal surface, said Dr. Stewart. “But if an edge is more adherent to the retina, you can use a bimanual technique with scissors and trim the corneal tissue. If a small remnant is left behind, it’s usually tolerated by the eye.” Dr. Schocket used a fragmatome to remove thicker material during a case of hers. (See video.)

Clinical outcomes. Patients typically do very well if the graft is removed promptly and PVR is managed successfully, usually with a placement of a scleral buckle to support the inferior vitreous base, said Dr. Stewart.

___________________________

1 Singh A et al. Cornea. 2010;29(11):1284-1286.

|

Managing Corneal Challenges During and After Surgery

Although some corneas may not heal as quickly as others, retina surgeons can take steps to lower the risks of corneal complications.

Protect nerves. Try to avoid laser photocoagulation at the 3 o’clock and 9 o’clock meridians along the course of the long ciliary nerves.

Keep the cornea moist. A buckle can prolong the surgical time, which increases the risk of the cornea drying out, said Dr. Schocket. Viscoelastic applied to the surface of the cornea can help. “But if I’m concerned about a cornea in a person who had LASIK or has diabetes, I may let the resident do less, so I can speed things along.”

Avoid scraping, if possible. Don’t scrape the corneal epithelium for visualization if you don’t have to, especially high-risk patients such as those with diabetes or a LASIK flap, said Dr. Schocket.

To reduce epithelial edema and corneal clouding, Dr. Tonk noted that, to the extent possible, it’s important to limit surgical case time, infusion pressure, and excess fluid volume passed through the eye (such as from leaky wounds). He added that surgeons can also use 50% glycerine to clear the cornea via osmotic action, obviating the need to scrape.

If you must scrape to achieve adequate visualization, said Dr. Stewart, try to remove relatively small areas of central epithelium. “A smaller epithelial defect has a better chance of healing in a shorter time. It’s not usually necessary to scrape the corneal epithelium out to the far peripheral portion of the cornea where the limbal stem cells are located.”

Alter post-op regimen. “A standard post-op regimen might include only a visit on post-op day 1 and post-op week 1,” said Dr. Stewart. “But patients who required scraping should potentially be seen more frequently to ensure the epithelium is healing and an infection is not developing.”

Don’t delay. “Surgeons must take decisive action to promote rapid corneal re-epithelialization,” said Dr. Tonk. Persistent epithelial defects that haven’t healed within four weeks of surgery, he said, are frequently associated with corneal haze and melt, or worse, infection or perforation.

Speed closure. “If you have scraped the epithelium,” said Dr. Tonk, “give yourself a strict timeline for partial and complete re-epithelialization—within a week or two, at the most.”

To speed closure, Dr. Tonk advises surgeons to do the following:

- Place a bandage soft contact lens at the time of surgery or the morning after.

- Use preservative-free artificial tears.

- Limit toxicity to the eye by modifying the use of eyedrops. For example, consider replacing glaucoma drops with an oral medication, reducing antibiotics to prophylactic dosing—typically two to four times a day—and reducing steroids to the minimum amount needed to reduce inflammation.

- Consider punctal occlusion.

Take aggressive steps—or refer. “If the epithelium has not closed within two weeks, treat aggressively as a per-sistent epithelial defect,” said Dr. Tonk. Surgeons might try autologous serum eyedrops (available through a local compounding pharmacy), temporary tarsorrhaphy, amniotic membrane (placed in the office or operating room), or the use of Oxervate (Dompé), a nerve growth factor, to treat NK.2

“But if you’re concerned about a post-op problem with the cornea,” said Dr. Schocket, “get it managed by a cornea specialist as quickly as possible so you know you have the best chance of healing the cornea.”

___________________________

1 Schmack et al. J Refract Surg. 2005;21(5):433-445.

2 Abdelkader H et al. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2011;39(3):259-270.

___________________________

Dr. Schocket is a vitreoretinal surgeon and associate professor, vice chair for clinical affairs, and chief of the retina division at the University of Maryland, Department of Ophthalmology, in Baltimore. Relevant financial disclosures: None.

Dr. Stewart is a vitreoretinal surgeon and professor of ophthalmology at the University of California, San Francisco. Relevant financial disclosures: None.

Dr. Tonk is a cornea specialist at Bascom Palmer Eye Institute and assistant professor of ophthalmology at the University of Miami Health System in Miami. Relevant financial disclosures: None.

For full disclosures and the disclosure key, see below.

Full Financial Disclosures

Dr. Schocket None.

Dr. Stewart Genentech: C; Roche: P; Valitor: C.

Dr. Tonk None.

Disclosure Category

|

Code

|

Description

|

| Consultant/Advisor |

C |

Consultant fee, paid advisory boards, or fees for attending a meeting. |

| Employee |

E |

Employed by a commercial company. |

| Speakers bureau |

L |

Lecture fees or honoraria, travel fees or reimbursements when speaking at the invitation of a commercial company. |

| Equity owner |

O |

Equity ownership/stock options in publicly or privately traded firms, excluding mutual funds. |

| Patents/Royalty |

P |

Patents and/or royalties for intellectual property. |

| Grant support |

S |

Grant support or other financial support to the investigator from all sources, including research support from government agencies (e.g., NIH), foundations, device manufacturers, and/or pharmaceutical companies. |

|

Removal of Posteriorly Located Corneal Donor Tissue Using the Fragmatome. This video demonstrates the use of a vitrector and a fragmatome to remove two pieces of corneal tissue from the vitreous cavity. (By Lisa A. Schocket MD, Zachary M. Bergman MD, Rebecca B. Bausell MD, and Bennie H. Jeng MD.)