By Robert M. Kinast, MD, Steven Hammerschlag, MD, and Rona Z. Silkiss, MD, FACS

Edited by Thomas A. Oetting, MD

This article is from October 2008 and may contain outdated material.

Stanley Michaels* is a charismatic athlete and tuba player. One day, after lifting weights before work, he noticed in the mirror that his right upper eyelid appeared a bit low. Later during that same day, the 42-year-old Caucasian began to experience right-sided headaches with shooting pain toward the base of his skull. Over the next week these headaches reappeared throughout the day but resolved after a good night’s sleep.

Initial Diagnosis

Mr. Michaels sought the advice of a neurologist who diagnosed him with cluster headaches based on their repetitive, unilateral and piercing nature. After treatment with prednisone and verapamil, the headaches resolved but the droopy eyelid remained unchanged.

We Get a Look

Three months after the initial incident, Mr. Michaels arrived at our oculoplastics clinic eager to have his right upper lid droop repaired. The patient was self-referred; his father had been our patient in the past. Mr. Michaels’ past medical history was pertinent for a pectus carinatum repair at age 16 and a subsequent diagnosis of sleep apnea.

He had a BCVA of 20/20 and IOP of 13 in both eyes. Ocular motility exam was normal. External exam revealed 3 mm of right upper eyelid ptosis with normal levator function. Pupillary evaluation revealed 1 mm of anisocoria, with the right pupil smaller than the left. This was more apparent in dim light. Both pupils reacted to light.

Slit-lamp and dilated fundus exam revealed no abnormality. Further cranial nerve and sweat gland evaluation were within normal limits.

|

|

External Examination. (Fig. 1) We noted right-sided ptosis and miosis.

|

Diagnosis Reconsidered

Aponeurotic dehiscence is the most common etiology of ptosis with normal levator function. There was, however, no history of trauma, surgery or contact lens use. Normal levator function decreased the likelihood of a myogenic etiology. Given the acute onset and coincident pupillary abnormality, Mr. Michaels’ ptosis appeared neurogenic in nature and secondary to Horner’s syndrome.

Horner’s syndrome with ipsilateral headache can have several causes, including cluster headache syndrome, Raeder paratrigeminal syndrome and carotid dissection. Along with unilateral repetitive pain, cluster headaches are accompanied by ipsilateral autonomic symptoms that can include ptosis, miosis, rhinorrhea, conjunctival injection, nasal congestion and lacrimation. Cluster Horner’s-like symptoms are typically episodic but can become permanent after repeated attacks. Raeder paratrigeminal syndrome is a diagnosis of exclusion when evaluating a patient with Horner’s syndrome and headache. It usually presents in middle-aged to elderly males with non-cluster pain of ophthalmic nerve distribution and without underlying pathology. Internal carotid artery dissection is the most feared cause of painful Horner’s syndrome due to the risk of embolic stroke. To aid in the diagnosis we urgently ordered magnetic resonance imaging and angiography of the head and neck.

|

|

|

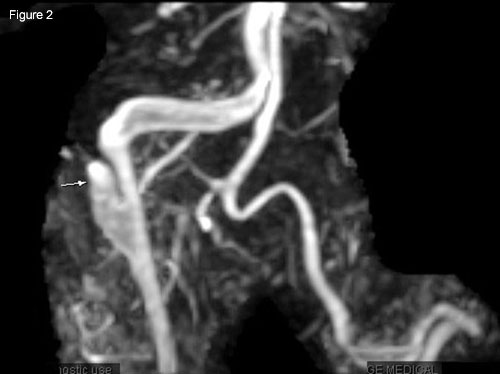

Radiology. (Fig. 2) MRA of right carotid shows false channel (arrow); intimal flap with narrowed true lumen (next to vertebral artery). (Fig. 3) Linear hypointensity (arrow) shows intimal flap separating true and false lumens; contralateral carotid reveals segmental dilation indicating pseudoaneurysm residual from prior dissection.

|

Treatment

MR imaging revealed bilateral high cervical carotid artery dissections proximal to the petrous bone, right worse than left. Follow-up laboratory studies revealed heterozygosity for factor V Leiden. We initiated anticoagulation therapy with warfarin (Coumadin).

Discussion

Horner’s syndrome is named after a Swiss physician, Johann Friedrich Horner, who first described it in 1869.

The syndrome is caused by a lesion along the oculosympathetic pathway, which extends in three segments from the hypothalamus through the superior cervical ganglion (1st and 2nd order segments) and terminates at end target tissues (3rd order segments). Because these targets include the facial sweat glands, the dilator muscle of the pupil and Müller’s muscle, the sympathetic lesions result in anhidrosis, miosis and ptosis, respectively. A few postganglionic nerve fibers track along the external carotid artery to the sweat glands of the lower face, but most fibers travel in the prevertebral layer of deep fascia behind the carotid sheath. Consequently, internal carotid dissection disrupts these 3rd order fibers.

Risk factors. These dissections are rare, with an annual incidence of 2.5 to 3.0 per 100,000. Only 4 to 17 percent of these cases are bilateral. Significant risk factors include trauma, strenuous exercise, fibromuscular dysplasia, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, connective tissue disease and smoking.

In addition to weight lifting, we postulate that sleep apnea, tuba playing, pectus carinatum deformity and factor V Leiden may have contributed to our patient’s bilateral dissections. His body habitus, tuba blowing and airway obstruction during sleep would have caused increased thoracic pressure that, like a Valsalva maneuver, could disrupt the vascular endothelium. Sleep apnea has been reported as a risk factor for dissection of the thoracic aorta, but not yet dissection of the carotid artery.1 A single case report links factor V Leiden with bilateral carotid dissection.2

Sequelae. These can widely vary from asymptomatic (e.g., our patient’s left-sided dissection) to a lower morbidity sympathetic disruption (e.g., our patient’s right-sided dissection) to severe morbidity and mortality (e.g., death from embolus).

A complex relationship. Both cluster headaches and carotid dissection have been reported to cause Horner’s syndrome. There are case reports of carotid dissection presenting as cluster headaches, with and without pupillary involvement. Cluster headaches usually include parasympathetic signs, like lacrimation and conjunctival injection; however, the pain of dissection can trigger a trigeminal-autonomic reflex and induce similar parasympathetic signs. In general, a diagnosis of cluster headaches should not exclude further investigation of underlying pathology.3 Clusterlike headaches can even respond to verapamil treatment in the setting of dissection, as seen in our patient and three case reports.4 A careful pupillary exam and follow-up is mandatory.

Mr. Michaels’ Case

Our patient remained on six months of warfarin for anticoagulation. This was discontinued by his vascular surgeon. He was thereafter maintained on aspirin therapy. His ptosis was repaired via a mueller’s muscle resection. The miosis has remained. Mr. Michaels has refrained from tuba playing and has modified his weight-lifting regimen.

___________________________

* Patient name is fictitious.

___________________________

1 Sampol, G. et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003;168:1128–1131.

2 Cardon, C. et al. Ann Vasc Surg 2000;12:503–506.

3 Rigamonti, A. et al. Headache 2008;48:467–470.

4 Tobin, J. and S. Flitman Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003;168:1128–1131.

___________________________

Dr. Kinast is a resident at the California Pacific Medical Center in San Francisco. Dr. Hammerschlag is a radiologist at Summit Medical Center and medical director at Medical Center Magnetic Imaging, both in Oakland, Calif. Dr. Silkiss is chief of the Oculofacial Plastic, Reconstructive and Orbital Surgery Division at California Pacific Medical Center in San Francisco.