By Eric A. Pennock, MD, John Mauro, DO, and John J. Huang, MD

Edited by Thomas A. Oetting, MD

This article is from October 2007 and may contain outdated material.

I am terrified I will go blind,” said Joseph Ozumba,* a 50-year-old musician originally from Africa. He was alarmed about his blurred vision and sadly recounted how his father lost vision at a similar age. Mr. Ozumba was passionate about reading and bird-watching and was not prepared to give these up.

His primary care physician had recently told him that he had type 2 diabetes mellitus and an initial blood glucose level that topped 600 mg/dl. The physician explained that the blurred vision may have been related to elevated levels of glucose, or even early diabetic retinopathy, and stressed that it was important for him to see an ophthalmologist. He then referred Mr. Ozumba to us for a routine diabetic eye exam.

We Get a Look

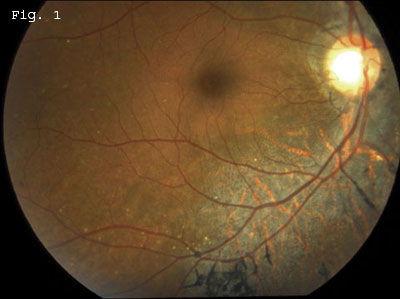

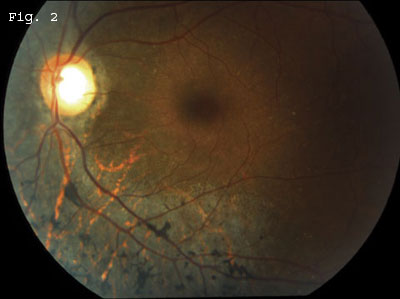

On examination, his BCVA was 20/20 in both eyes. The anterior segment was unremarkable, and the fundus exam did not reveal any evidence of diabetic retinopathy. There was vitreous syneresis with no evidence of vitreous cells. The cup-to-disc ratio was increased, and fundus ophthalmoscopy was remarkable for nonglaucomatous peripapillary atrophy as well as peripapillary hyperpigmentation in both eyes. There was slight attenuation of retinal vasculature bilaterally. Posterior fundus examination revealed diffuse retinal pigment epithelium mottling with RPE migration in a bone spicule pattern seen predominately adjacent to all the retinal vessels in both eyes. These changes were concentrated inferiorly but were present in all four quadrants of the retina. Large circular areas of RPE atrophy with prominent underlying large choroidal vessels were present in areas of RPE mottling (Figs. 1 and 2).

|

|

A DIABETIC WITH BLURRY VISION. Mr. Ozumba was referred to us for a routine diabetic eye exam. We noted pigmentary retinopathy in a bone spicule pattern along the retinal vessels, as well as peripapillary atrophy.

|

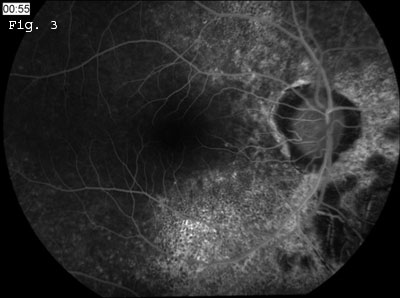

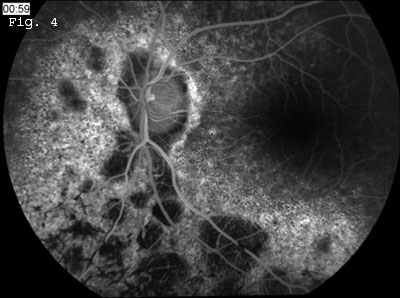

Fluorescein angiography was performed (Figs. 3 and 4), and the early images showed normal retinal and choroidal vascular filling with no evidence of leakage late on the angiogram. There was diffuse early hyperfluorescence in the areas of pigment epithelium mottling surrounding the disc and adjacent to the retinal vessels, consistent with a transmission defect. There also were nummular areas of hypofluorescence concentrated predominately in the inferior fundus. These “leopard spots” indicated a filling defect from loss of choriocapillaris in the areas of RPE atrophy. There was diffuse blocked fluorescence that corresponded with the numerous hyperpigmented bone spicule lesions.

|

|

FLUORESCEIN ANGIOGRAPHY. We noted diffuse hyperfluorescence caused by pigment epithelial transmission defect. There were multiple areas of nummular hypofluorescence inferiorly that indicate loss of choriocapillaris.

|

Differential Diagnosis

A myriad of diseases can be associated with pigmentary retinopathies. Most can be divided into congenital, infectious, autoimmune and toxic etiologies.

Retinitis pigmentosa and its subtypes are a group of hereditary disorders commonly associated with pigmentary retinopathy, nyctalopia and constricted visual field, and, particularly for autosomal recessive and x-linked RP, with early progressive vision loss. The disorder can be transmitted in an autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive and x-linked inheritance pattern. In addition, retinitis pigmentosa can be part of the constellation of disorders seen in systemic diseases and syndromes, such as Bardet-Biedl, Bassen-Kornzweig, Kearns-Sayre, Refsum’s, Stargardt’s and Usher’s.

Salt-and-pepper fundus with diffuse pigmentary lesions can be the signature of a previous systemic infection that had ocular involvement. Examples include inactive chorioretinal scars secondary to Lyme disease, tuberculosis, syphilis, congenital rubella, toxoplasmosis and bartonellosis.

A variety of pharmacologic agents taken at a high dose and for an extended duration such as chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine and thioridazine can all lead to pigmentary retinopathies as well.

Our patient’s history was inconsistent with a progressive retinal degeneration, such as retinitis pigmentosa, and the patient has no past history of chronic prescription medication. Although Mr. Ozumba had no signs or symptoms of active systemic disease, it was necessary to rule out an infectious or autoimmune etiology. His workup included a complete blood count with differential, basic metabolic panel, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, angiotensin converting enzyme, antinuclear antibody, rapid plasma reagin (RPR), fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-ABS), Lyme titers and Bartonella titers.

The lab results were unremarkable with the exception of a reactive RPR and a positive FTA-ABS, indicating a past or current syphilis infection.

Discussion

Syphilis is an infection caused by the spirochete bacterium Treponema pallidum, and it is often divided into primary, secondary and tertiary stages.

Increasingly prevalent. Over the last several years there has been an increase in the number of reported syphilis cases, as well as outbreaks in major U.S. cities and surrounding areas. Socioeconomic factors, bacterial resistance and increasing high-risk sexual practices are thought to have contributed to the recent rise in syphilitic infections. Coinfection with HIV increases the risk of fulminant disease and the likelihood of ocular complications.1-5

Primary stage. The hallmark of primary syphilis is a chancre. This painless papule appears at the initial inoculation site three weeks after exposure.2 Even without treatment, the chancre will heal—but by this time the spirochete will have disseminated through the blood and lymphatic system.

Secondary stage. Approximately four to 10 weeks after appearance of the chancre, the patient may develop secondary syphilis. Patients at this stage most commonly present with fever and a maculopapular rash on the palms and soles. During this stage, ocular manifestations include conjunctivitis, episcleritis, interstitial keratitis and anterior uveitis. Focal or multifocal chorioretinitis, retinal arteritis or perivasculitis, cystoid macular edema, serous retinal detachment and optic neuritis can also be present.1-5 Placoid gray-white or yellow subretinal lesions have been described in conjunction with vitritis, an entity known as acute syphilitic posterior placoid chorioretinitis. Such lesions are usually seen in patients with concomitant HIV infection.1,4

Latent syphilis. A latent form of syphilis is characterized by positive serologic tests despite the absence of symptoms. Early latent syphilis is defined as known exposure to syphilis, or the development of primary or secondary syphilis symptoms within the past year. If the time from exposure is unknown or is greater than one year, it is classified as late latent syphilis.

Tertiary stage. The final stage of syphilis can occur as late as 50 years after the initial inoculation. With concomitant involvement of the central nervous system, it is called neurosyphilis. Ocular findings in this stage can include those listed above, with the addition of Argyll-Robertson pupil and optic atrophy.3 As in secondary syphilis, uveitis is considered to be the most common ocular presentation of active disease. Tertiary syphilis can also present with evidence of prior inflammation, as seen in our patient. The hyperpigmented lesions in the bone spicule pattern are consistent with RPE migration into areas of retinal inflammation and damage. In this setting it is also referred to as “pseudoretinitis pigmentosa.” The window defects seen on angiogram are consistent with chorioretinal atrophy.

Diagnosing “The Great Masquerader.” Since no ocular finding is truly pathognomonic, and the physical signs of primary and secondary syphilis are transient, the diagnosis and subsequent treatment of syphilis is often delayed.

Serologic testing must be performed to make the diagnosis and start appropriate antimicrobial therapy. In most cases a nontreponemal test, such as RPR or Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL), is performed first. If positive, this is followed by a treponemal test—such as FTA-ABS or microhemagglutination assay for T. pallidum (MTA-TP)—for confirmation. In tertiary syphilis, however, the RPR and VDRL can be falsely negative in 30 percent of patients.3,5 This is especially relevant to ophthalmologists since ocular manifestation of syphilis often coincide with late stages of the disease process. Thus a treponemal test (FTA-ABS or MTA-TP) should always be performed if the clinical suspicion for syphilis is high. When clinical findings are suggestive of neurosyphilis, cerebrospinal fluid may be obtained for testing as well. If initially positive, nontreponemal assays are useful in evaluating response to therapy.

Treatment is considered to be effective if the RPR or VDRL titers decrease by fourfold after six months for treatment of early syphilis and after 12 months for treatment of late syphilis.3 Syphilis patients with concomitant HIV infection often present with an aggressive posterior segment inflammation. Thus, all syphilis patients with chorioretinal manifestations should undergo additional HIV testing.1,5 This may lead to early diagnosis and concurrent antiretroviral therapy.

Treatment

The recommended therapy for early active syphilitic infection is intramuscular penicillin G, given in a single dose of 2.4 million units.1-4 Patients with late latent or tertiary syphilis receive three additional intramuscular injections of benzathine penicillin G, given one week apart. Patients who are penicillin allergic may be started on doxycycline, erythromycin or tetracycline. Consultation with an infectious disease specialist is also recommended. All sexual contacts should be identified and undergo serologic testing. In addition, syphilis is a reportable infection and the local department of health should be notified.

Mr. Ozumba had no recollection of past exposure to syphilis and hence was treated for latent syphilis of unknown duration. His job required frequent out- of-town travel and he was unable to get the weekly dose of penicillin. He was started on oral doxycycline 100 mg twice a day for one month. After three months, repeat RPR titers were significantly lower.

___________________________

* Patient’s name is fictitious.

___________________________

1 Chao, J. R. et al. Ophthalmology 2006;113:2074–2079.

2 Golden, M. R. et al. JAMA 2003;290:1510–1514.

3 Aldave, A. J. et al. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2001;12:433–431.

4 Gass, J. D. M. et al. Ophthalmology 1990;97:1288–1297.

5 Browning D. J. Ophthalmology 2000;107:2015–2023.

___________________________

Drs. Pennock and Mauro are residents at Nassau University Medical Center, N.Y., and Stony Brook University Hospital, N.Y. Dr. Huang is assistant professor of retina and uveitis at the Yale Eye Center, New Haven, Conn.