This article is from July/August 2006 and may contain outdated material.

Myasthenia gravis, the neuromuscular disorder caused by antibodies to acetylcholine receptors, is well-known to ophthalomologists. And, in fact, ophthalmologists often are in a position to make the initial diagnosis, since ptosis and diplopia are common presenting symptoms.

Moreover, ophthalmologists may be in a position to make a difference in the overall course of the disease. A significant number of patients who first complain of only ocular symptoms will progress to generalized myasthenia. And recent studies have raised the possibility that ophthalmologists may be able to intervene and prevent the progression from ocular myasthenia to systemic disease.

Getting a Diagnosis

Ocular myasthenia can mimic any gaze and/or pupil-sparing nerve palsies. However, variability and fatigability are the clues that you’re dealing with myasthenia. “You might see medial rectus weakness in one eye and abducting nystagmus in the other and think that it is an internuclear ophthalmoplegia,” said Robert L. Lesser, MD, clinical professor of ophthalmology and visual science and neurology at Yale University. “But if it improves when the patient is rested, or there is variability, then it is more likely that it is myasthenia.”

|

|

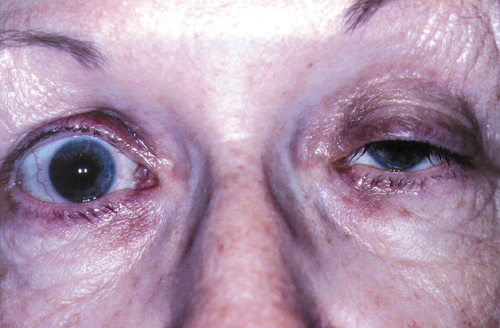

MUSCLE MALAISE. A 72-year-old woman with myasthenic ptosis in left eye and contralateral pseudo-lid retraction.

|

In-Office Tests

Tensilon test. While the edrophonium (Tensilon) test has long been the standard in-office test for myasthenia, a number of neuro-ophthalmologists are using it much less frequently. “For any patient with at least 2 mm of ptosis, I use the ice test, which is quicker, easier and safer,” said David A. Weinberg, MD, associate professor of ophthalmology and visual science at the University of Utah, Salt Lake.

“I do the ice and sleep tests all the time; when they’re positive, I’m usually willing to make the diagnosis of myasthenia. And I won’t do the Tensilon test at that point,” said Dr. Lesser.

However, as Dr. Weinberg pointed out, “For a patient with a slight [1.5 mm or less] ptosis or no ptosis at all, who is experiencing other signs of weakness, such as diplopia, facial or orbicularis weakness, or limb weakness, the Tensilon test is a reasonable option.”

Ice test. For this test, the patient applies an ice pack to his or her eyelid for about two minutes. A positive result is what Dr. Lesser described as “dramatic improvement” in the ptosis. “There should be at least 2 mm improvement in upper eyelid height,” Dr. Weinberg said. (For objective documentation, photograph the patient before and after the test.) “Patients don’t necessarily like this test, as it can be uncomfortable, but I use it all the time,” said Dr. Lesser.

If the patient has diplopia but no ptosis, “The ice test can still be used,” said Dr. Weinberg. “In this case, the ice is applied for five instead of two minutes.” He cautioned, however, that using the ice test for diplopia is not as well accepted as it is for ptosis, “and the assessment of ocular motility and alignment must be performed rather expeditiously—that is, before the improvement secondary to cooling wears off.”

Sleep test. For this the patient rests in a quiet, darkened room for about 30 minutes, and measurements of either the ptosis or eye movements are taken before and after sleep. “Again, we’re looking for a dramatic and significant change,” Dr. Lesser said. The sleep test —which he described as “a wonderful test”—has been found to be sensitive and specific.1

Lid fatigue test. This test, having the patient look in extreme upgaze for at least one to two minutes, assesses for fatigability of the levator muscle and can be used to confirm the results of the ice and sleep tests.

Lab Tests

Acetylcholine receptor antibodies. An elevated titer can confirm the diagnosis, particularly in generalized myasthenia, since false positives are rare with this test. However, a normal titer doesn’t exclude the disease: As many as 10 percent of patients with generalized myasthenia and 60 percent of those with ocular myasthenia will test seronegative. As a result, it can be worth retesting patients after several months. “While binding antibodies are the most prevalent, it may be worthwhile also testing for blocking and modulating antibodies when there is significant clinical suspicion of myasthenia,” Dr. Weinberg added.

Anti-MuSK antibodies. Antibodies to a muscle-specific receptor tyrosine kinase (MuSK) have been found in approximately 40 percent of patients with generalized myasthenia who are negative for the acetylcholine receptor antibodies.

Recent case reports indicate that anti-MuSK antibodies also may be found in patients with exclusively ocular findings. “I’m aware of two patients who have ocular myasthenia and antibodies to MuSK,” Dr. Lesser said. At this time, he doesn’t order MuSK routinely.

Thyroid function. Because of the association with thyroid disease, “I always order thyroid function tests,” said Dr. Lesser. Either hyper- or hypothyroid disease may be associated with myasthenia.

Other screening. Dr. Lesser also considers serology screening for vasculitis and anemia. And while it’s a relatively rare syndrome, he checks for autoimmune polyendocrinopathy type 2, which is characterized by diabetes, anemia, celiac disease, Addison’s disease and vitiligo. “It’s rare, but I ask about these diseases as part of the patient history.”

Choosing a Treatment

Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors. Pyridostigmine (Mestinon) and neostigmine (Prostigmin) are commonly used as first-line treatments for ocular myasthenia; pyridostigmine usually is preferred because it tends to be better tolerated. However, these drugs may be more effective in treating ptosis than diplopia.

“I believe that Mestinon should be the first line of treatment, even though it is often ineffective or inadequately effective. Some colleagues prefer to go straight to oral prednisone, which is generally my second line of treatment,” Dr. Weinberg commented.

Prednisone. Prednisone has won a place in treating ocular myasthenia primarily because of its ability to help alleviate diplopia. “I use prednisone because it works in most cases,” Dr. Lesser said. “With Mestinon, you may be able to improve diplopia by 50 percent, but the patient will still have diplopia.”

And prednisone may even do more for patients. “In addition to often being quite effective, prednisone has the advantage of possibly preventing ocular myasthenia from becoming generalized myasthenia, which is more serious and potentially life-threatening,” Dr. Weinberg noted. “However, while there are a number of small, nonrandomized studies suggesting that prednisone prevents generalization of ocular myasthenia, the ‘proof’ is pending.”

Those nonrandomized studies include a retrospective review of 147 patients, in which those treated with prednisone had a 7 percent conversion rate to generalized myasthenia, vs. a 36 percent conversion rate seen in those who received either Mestinon or no treatment.2

In a second retrospective review of 56 patients, Dr. Lesser and his colleagues found an 11 percent conversion rate in those treated with prednisone, vs. a 34 percent conversion rate in those who had received no treatment.3

Prednisone may be able to halt progression by increasing the number of acetylcholine receptors, preventing further receptor loss and increasing the depth of postsynaptic folds, Dr. Lesser said. In any event, as he put it, the real question is, “If you intervene earlier, will the symptoms be less severe?” A large, multicenter, prospective, randomized study of this question is in the works; it is expected to include 25 clinics and recruit 240 patients over a two-year period. “Patients will be randomized to receive either placebo plus pyridostigmine or prednisone plus pyridostigmine,” Dr. Lesser said.

Other options. The steroid-sparing agents used to treat generalized myasthenia may be used for patients with ocular myasthenia. For instance, Dr. Lesser noted, “With prednisone, I typically start a patient at 40 mg or more per day, then work at getting them down to a maintenance dose over a three- to six-month period. If this isn’t possible, I work with a neurologist to move them to CellCept [mycophenolate mofetil] or Imuran [azathioprine].”

_______________________________

1 Kupersmith, M. J. et al. Arch Neurol 2003;60:243–248.

2 Monsul, N. T. et al. J Neurol Sci 2004;217:123–124.

3 Odel, J. G. et al. J Clin Neuroophthalmol 1991;11:288–292.

________________________________

Drs. Lesser and Weinberg report no related interests.