By Cristos Ifantides, MD, MBA, and Prem S. Subramanian, MD, PhD

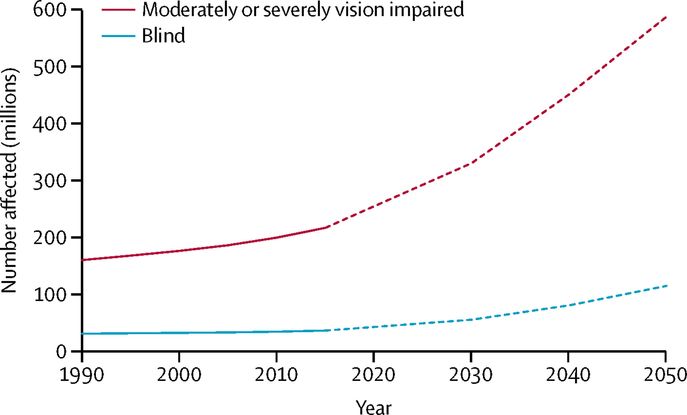

Over the last 30 years, age-specific blindness prevalence decreased by 36.7%. However, due to explosive population growth and an aging populace, the total number of visually impaired people has grown dramatically. Today, approximately 1.3 billion people live with some form of visual impairment around the world.1 These numbers reflect a 17.6% increase in the number of blind people and a 35.5% increase in moderate to severe visual impairment over the last three decades.2

An estimated 500,000 children become blind each year. In developing countries up to 60% of children are thought to die within a year of becoming blind.3 As illustrated in Figure 1, we must reassess our strategies and scale up our efforts just to maintain the status quo. However, if we intend to cure global blindness, the direction of our efforts will need to change.

|

|

Figure 1. Global trends and predictions of numbers of people who are blind or moderately and severely vision impaired, from 1990–2050. Reprinted from Bourne et al.1 under a CC-BY 4.0 license.

|

The traditional approach to alleviating visual impairment uses a mix of individual, governmental, and non-governmental organization (NGO) efforts. These efforts focus on performing vision-restoring surgeries, occasionally paired with lectures and/or surgical wet labs for local personnel. These efforts convey great personal satisfaction and provide direct and tangible services to the patients treated. However, they cannot adequately meet the current need, let alone solve the growing burden of blindness.

In light of such a challenge, we are not proposing a specific strategy for global ophthalmology, but rather, a re-assessment of our efforts. We hypothesize that the most feasible approach to solving reversible and irreversible blindness is the creation of good jobs within the ophthalmology space. Building healthy local economies of eye care will be the only lasting way to solve this growing problem. So how do we create healthy economies of eye care abroad? We must recapitulate the same incentives that cause eye care providers to thrive here at home.

Ophthalmology is a secure and rewarding profession in countries where blindness remains low. These countries financially reward surgical procedures that treat visual impairment. Meaningful work paired with comfortable pay has led to a demand for eye care jobs. This valuation of ophthalmology exists in most high-income nations regardless of payment models. Nonetheless, representatives from the high-income nations have viewed low- to middle-income countries with a sense of eye care exceptionalism. We plan interventions abroad that, if implemented here at home, would destroy our eye healthcare economy.

Below, we highlight many of the issues we have created due to our exceptionalism, followed by suggestions on how we can start thinking differently.

Actions that have hindered ophthalmology from being a great profession abroad

The easiest way to see the destructive force of our actions is to apply our current outreach policies domestically. As a fictitious example, consider an American ophthalmology graduate, trained in both phaco and manual small incision cataract surgery (MSICS). She seeks a good job, meaning one with excellent clinical and surgical volume that will provide personal and financial fulfillment. Good patient volume also translates into a strong eye care market allowing her to hire adequate staff, buy up to date equipment, and get access to disposables. She offers both phaco and MSICS based on patient desire and ability to pay.

Now imagine if there are visiting ophthalmology groups from Canada that travel to her city and do thousands of no-charge phaco surgeries each year. Soon, the American surgeon realizes that both poor patients and those who could afford to pay typically wait for the visiting Canadians to get their surgery, as the Canadians do not (nor could they effectively) screen patients for their ability to pay. The American ophthalmologist can’t compete with free-of-charge phaco, and her surgical practice becomes non-existent. She is forced to stop doing surgery and start focusing on offering services for which patients are willing to pay, such as refractions and optical shop products. Local surgical care is devalued, and patients lose a local resource.

An even worse outcome might result. Prior to setting up her practice, the American ophthalmologist hears about the visiting Canadians. The American realizes that patients are willing to wait and travel from surrounding cities and states to get free surgical services from the visiting Canadian groups. The American ophthalmologist decides to not set up a practice anywhere near that area. As a result, the patients of that area remain dependent on the Canadian surgical groups. Diseases like glaucoma, retinopathies, and other chronic diseases that need regular, local ophthalmologic care go undiagnosed and untreated.

The irony of this situation is that the Canadians were well-intentioned and came to help. They gave up money and time to do what they thought was the right thing. And yet, the lack of communication with local ophthalmologists and free services offered to patients who could have paid for surgery led to a destruction of the local cataract surgery economy. It is an economic reality in the USA and abroad that nobody can compete with the destructive forces of free products. Good intentions without good guidance will recreate these undesirable situations over and over again.4

Education without good jobs leads to wasted resources

Educational activities for local providers during medical mission trips are usually very practical and directed. Yet, we should not assume that it will be effective if we do not take economic factors into consideration. Our efforts and those of our students are wasted if we teach skills that will never be used because of lack of a market. Unfortunately, we have poured massive amounts of human and financial resources into training ophthalmologists who will never be able to make a decent living doing surgery.

It should be no surprise that these freshly minted surgical ophthalmologists stop operating in places where people can get free-of-charge cataract surgery if they wait for visiting ophthalmologists. They just can’t compete with “free.” Thinking in these terms, it becomes understandable when we see an ophthalmologist’s activities revolve around services that have a market, such as refraction services and optical shop products.

Furthermore, doctors abroad may have family and financial obligations that far exceed our own. Perhaps an entire extended family saved up for this one person to go to medical school. Private school for the ophthalmologist’s children can be very costly and may be the only real option for a meaningful education. This is reflected in an estimated one-fifth of African born physicians working in high-income countries rather than staying and practicing at home.5

Understanding these pressures and knowing what we would do in those situations is critical to correcting our policy of exceptionalism. They are just like us, but with different socioeconomic pressures. If a service does not pay, the service will not be offered, regardless of whether they are skilled in this service or not.

The Role of Industry

Industry has been a crucial partner in our global ophthalmology work for decades. However, industry has looked towards ophthalmologists and NGOs to self-manage donations and ensure delivery to the neediest. Unfortunately, if the mission group does not screen for need, then industry ends up supporting outreach efforts that take resources away from the poor and gives it to those who can afford to pay. This support is not in the company’s humanitarian or long-term business interests. Because the paying patients are not contributing to the local eye care economy, a local market for the company’s products never takes hold. This system drives up reliance on donations while hindering a sustainable supply chain.

What’s worse, poorly funded government systems and private practices struggling to stay afloat are left to deal with the aftermath. Removing the paying patients’ revenue while leaving the poorest patients to rely on fragile eye care systems ends up doing the reverse of what we intended to do – help. This damage caused by the influx of donated product into low-income countries is not unique to the medical industry. This economic damage can be seen throughout numerous local industries that have had to compete with donated free products such as textiles, building supplies, and other technologies.6,7

Policy Proposals

Our proposals cannot be implemented without the participation of existing small outreach groups, NGOs, and industry. Indeed, the buy-in of these kind-hearted, hardworking groups is essential as we work towards a common goal.

Solutions For Private Groups

One way to offset the negative effects of free products is by offering product differentiation. Institutions like the LV Prasad Eye Institute in India are great examples of this strategy, offering different levels of surgical options. They offer free MSICS for their poorest patients, but charge for other services such as phaco surgery. Patients who opt for phaco surgery pay into the system, which then helps subsidize the non-paying MSICS patients. If visiting surgical groups follow a similar model, they can actually help generate revenue by charging for phaco surgery. These funds can then be used to improve local eye care access. If these visiting groups are not skilled in MSICS, even something as simple as charging patients to skip the waiting list can generate income for the local economy.

Another technique we can use is to depend on local eye care providers for patient screenings. There are fantastic groups such as the Himalayan Cataract Project who offer free MSICS surgery while preserving the local eye care economy. This is due to their close collaborations with local eye care providers who screen for the poorest individuals. Additionally, they avoid doing free phaco surgery since it is not cost-effective. This strategy helps the poorest individuals while retaining paying patients for the local providers.

In general, we should:

- Connect with the nearest ophthalmologists or eye care system(s) within the country.

- Assure them we are not there to take paying patients away from their practice.

- Ask them if they can help with the screening process to ensure the neediest patients get our help.

- Reassess the needs of a region before returning, especially when prior trips may have occurred without a local contact being available.

- Support the local ophthalmologist(s), especially those trying to set up new practices.

- Ensure local providers understand that we are dedicated to returning and continuing to support their work, but also that we are willing to move on to other areas in greater need once we help them establish a local system of care.

Solutions for Industry

Industry has the power to decide whether an outreach program is sustainable or not and dispense products accordingly. Ensuring that free-of-charge supplies go to the neediest patients helps satisfy both the humanitarian and business imperatives that drive their donations. We ask industry leaders to consider their work as building roads to a destination. They need to know where the next stop is in order to see how their work contributes to the overall goal.

Questions that industry should ask each outreach group include:

- What is the long-term strategy and is there an exit strategy (plan to hand off the operation to someone locally)?

- What is the timeline and milestones for declaring success?

- With whom will they be working with locally?

- Documentation of communication with local providers to set up care.

The other crucial piece of the puzzle is to improve communication amongst all groups going abroad to do work. Lack of communication leads to different outreach groups working in similar spaces without knowing about one another. We pass each other like ships in the night when we should be joining forces as an armada against blindness. Currently, the International Council of Ophthalmology provides some coordination of efforts by participating NGOs, but smaller groups are missed. Industry can solve this issue, since most surgical mission trips require some degree of industry support. By publicly sharing group contact information, dates of travel, purpose, and location, we can begin to see who is working where and create group strategies to help. Industry has the ability to help us with this communication and can lead the way to reform.

Summary

As the field of Global Ophthalmology develops into its own subspecialty, many of these principles will become clearer. The role of global ophthalmologists is to study these intricate parts and devise solutions to grow our field’s impact. If outreach groups or industry members have questions regarding whether their strategy is helping or harming, please reach out.

If we can achieve the above, we will have an organized system that can evaluate the greatest need abroad, ensure outreach groups target the neediest patients, help local ophthalmologists thrive, and create new robust markets for industry. In this system, everyone wins, especially (and most importantly), the poorest patients who are most in need.

Citations

- Bourne RRA, Flaxman SR, Braithwaite T, Cicinelli MV, Das A, Jonas JB, et al. Magnitude, temporal trends, and projections of the global prevalence of blindness and distance and near vision impairment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2017;5(9):e888-e97.

- Fricke TR, Tahhan N, Resnikoff S, Papas E, Burnett A, Ho SM, et al. Global Prevalence of Presbyopia and Vision Impairment from Uncorrected Presbyopia: Systematic Review, Meta-analysis, and Modelling. Ophthalmology. 2018;125(10):1492-9.

- WHO. World Health Organization. Preventing blindness in children: report of WHO/IAPB scientific meeting. 2000.

- Miller, M.M. (Director/Producer/Writer), Witt, J. (Writer). Poverty, Inc. United States of America: Passion River; 2014. p. 91 minutes.

- Duvivier RJ, Burch VC, Boulet JR. A comparison of physician emigration from Africa to the United States of America between 2005 and 2015. Hum Resour Health. 2017;15(1):41.

- Wadhams N. Bad Charity? (All I Got Was This Lousy T-Shirt!) Time Online: Time; 2010 [Available from: http://content.time.com/time/world/article/0,8599,1987628,00.html.

- Swanson A. Why trying to help poor countries might actually hurt them: The Washington Post; 2015 [Available from: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2015/10/13/why-trying-to-help-poor-countries-might-actually-hurt-them/?noredirect=on.

Dr. Ifantides is with the Department of Ophthalmology, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora, Colorado, USA, and Division of Ophthalmology, Denver Health Medical Center, Denver, Colorado, USA.

Dr. Subramanian is with the Departments of Ophthalmology, Neurology, and Neurosurgery, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora, Colorado, USA.