Author: Aubrey Minshew, Museum Specialist, Truhlsen - Marmor Museum of the Eye®

Folsom State Prison, California

Folsom State Prison, CaliforniaThe name “Folsom State Prison” can bring up a wide variety of associations. For instance, one might be inspired to hum a few bars from Johnny Cash’s legendary live album recorded there. Or, one might rattle off a list of famous (or infamous) people who were incarcerated there in the past: Charles Manson, Eldridge Cleaver, or maybe Suge Knight. Or, perhaps more personally, the name Folsom might bring up an emotional connection to a friend or family member that spent time there, as a prisoner or as a guard. However, not many people hear the name Folsom and immediately think of Braille. But perhaps they should.

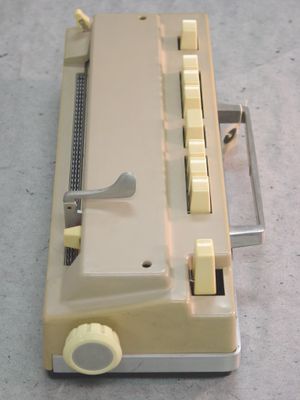

I had the opportunity to visit Folsom State Prison in the fall of 2018. Folsom sits in the green hills north of Sacramento, California, a series of otherwise beautiful stone buildings perched on a bluff over the American River. Inside the prison, there is a completely self-sufficient world of incarcerated people and prison employees, all living lives separated from the outside. As a person with no personal experience or connections with the penal system, all of this was astonishing to me. But the most astonishing thing I saw at Folsom was a warehouse full of books in Braille and a small battalion of inmates typing away on Perkins Braillers.

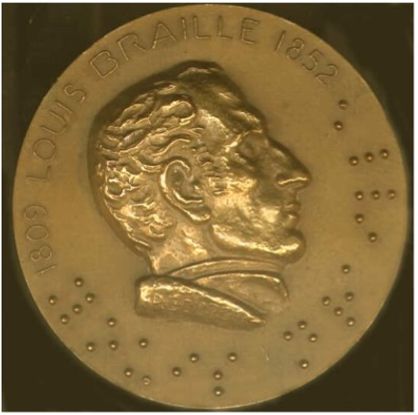

Braille is one of the best-known aids for people who are blind or who have low vision. Braille is not a language, like English or American Sign Language, but rather a code to translate any language into a series of raised dots that can be read by hand. Developed by Louis Braille (1809-1852) in 1829, Braille writing has gone on to become the accepted standard for creating reading material for people who are blind. Braille can be used to convey literature, mathematical equations, scientific formulas, and even sheet music. American Braille translators undergo rigorous training from the Library of Congress’s National Library Service for the Blind and Print Disabled. As of 2017, there were only about 600 people certified in literary Braille, about 400 people certified in Nemeth (Braille for science notation), and only 30 people certified in music Braille.

One tenth of those specialized translators are inmates at Folsom State Prison. Under the California Prison Industry Authority, people incarcerated at Folsom can pursue all of the Library of Congress’s Braille certifications, which gives those incarcerated both an opportunity work in a quiet space outside of the hustle and bustle of the prison yard, and set of marketable skills they can use after they complete their sentences. Since 1989, people at Folsom have taken to Braille translation with great enthusiasm. In fact, there are only 12 individuals living in the world today who hold all three of the Library of Congress’s certifications, and three of those people are incarcerated at Folsom.

Back in 2018, I had the opportunity to speak with one of those three people. Layale Shellman, who is currently serving a life sentence for a murder he committed in in the 1970s, achieved six separate Braille certifications in six years. When I met him, Mr. Shellman was hardly what one might expect. I found him to be a very kind and unassuming person, a shorter man with a head full of white hair, and an expressively devout Christian. Braille has now become his passion and life’s work, and he often develops penpal-like relationships with people who are blind. Often, they send him requests for new books or pieces of music that they would like to learn. He did not fit my mental image of an incarcerated person, and I doubt that he fits squarely into many people’s perceptions of an accessibility professional.

There is a patchwork of professionals and practitioners who work together to provide accessibility aids and lifestyle care for people with low vision and people who are blind. The Braille translators at Folsom State Prison are just one part of this greater tapestry but they contribute to this community with as much enthusiasm as anyone outside the prison walls. My visit to Folsom State Prison gave me a much more nuanced picture of incarcerated life and expanded my associations with the people of Folsom. I think of Layale Shellman and the other Braille translators any time I see Braille in the wild, and I am grateful to have had the opportunity to widen my understanding of just how that Braille got there.

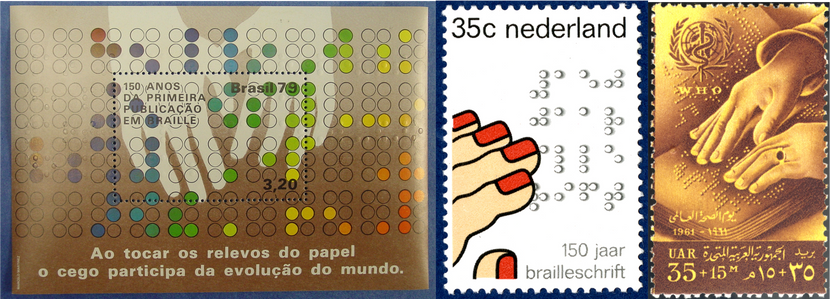

A Collection of Stamps Celebrating Braille, c. 1975

January 4th is World Braille Day! World Braille Day is observed each year by the United Nations on Louis Braille’s birthday. If you want to learn more about Louis Braille, check out his biography on the museum’s website. For more Braille-related artifacts, use the “Collections Search” function on the museum website or the museum’s mobile app, available for free from Google Play and on the App Store.