Author: Aubrey Minshew, Museum Specialist, Truhlsen - Marmor Museum of the Eye®

October is a great month for a medical museum and for an eye museum in particular. Not only is there a preponderance of eyeball-related merchandise on the shelves, but it also gives us an opportunity to talk about some of the wilder turns in the path to modern medicine. This October, the museum is highlighting some of those stranger stories in our newest tour and gallery guide, Ocular Oddities: Weird and Wild Stories in Ophthalmology.

Join us as we search through the museum’s collection and galleries for stories of dissections, bloodletting, and even dueling doctors. Learn about how you don’t need to be afraid of your eyeballs popping out of your head like you see in the movies. In the long history of ophthalmology, the truth is often stranger than fiction!

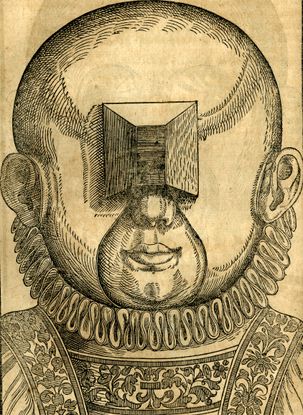

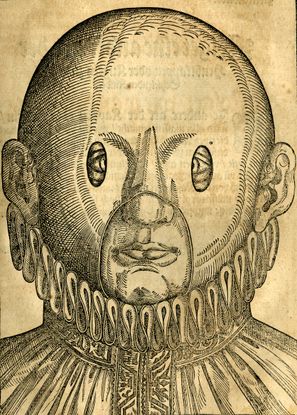

For instance, the museum features these woodcuttings from a 1583 book by German physician Georg Bartisch. Bartisch postulated that full-coverage masks like these could be used to treat strabismus by “training” the eyes to only look in certain directions. But did you know that Dr. Bartisch had an interesting theory about strabismus’s cause? He was a proponent of the theory of maternal imagination, a popular medical theory during the Renaissance that taught that congenital birth defects were caused by a pregnant woman’s ill or strange thoughts. In the same writings as the strabismus masks, Bartisch suggested that a mother could cause strabismus in her child if she had looked at “shining armor, fire and storm, lightening, gunfire, the sun reflecting in the water, [and] also at dying people collapsing from severe infirmity” during her pregnancy. Another popular explanation at the time suggested that a child might have webbed fingers or toes if the mother was startled by a frog during her pregnancy!

Ocular Oddities: Weird and Wild Stories in Ophthalmology will be featured at the museum throughout the month of October. Ocular Oddities will soon be a virtual tour that you can access from home via the museum app as well.

More From Aubrey Minshew - Museum Specialist - A Fascinating Intersection Between History and Science

During my first few weeks here at the Museum of the Eye®, I have been delighted to learn more about the history of ophthalmology and surprised to discover how this specific subset of medicine has both been shaped by major historical events, and how ophthalmologists took those events as an opportunity to push their science to new heights.

During my first few weeks here at the Museum of the Eye®, I have been delighted to learn more about the history of ophthalmology and surprised to discover how this specific subset of medicine has both been shaped by major historical events, and how ophthalmologists took those events as an opportunity to push their science to new heights.

For instance, as San Francisco celebrated Fleet Week this month, I originally did not see a connection between ophthalmic history and the fighter jets flying over the museum. Then, I had a chance to learn more about the history of flight medicine and how ophthalmologists were on the front lines of learning to care for pilots and one of their most important assets: their eyes! I was really drawn to the story of the development of the first intraocular lens by Dr. Harold Ridley. Dr. Ridley left his position at the Royal London Ophthalmic Hospital at the beginning of the Second World War to help care for wounded pilots during the Battle of Britain. During this act of service, he was able to make observations about how well these pilots’ eyes tolerated injuries from their shattered airplane canopies. He used his background as an ophthalmologist to care for these men, and he then took those observations and later started using that same plastic from the airplane canopies to create artificial lenses to be used in cataract surgeries. I thought this was an astonishing example of how ophthalmology was crucial during an event so defining as WWII, but also as an example of how WWII created an opportunity for ophthalmologists to take lessons out of tragedy to enhance future generation’s vision. I look forward to discovering more about the interconnected nature of history and science as I help welcome visitors to this fantastic new museum.

If you want to learn more about the history of flight medicine, check out Eyes to the Sky: A Tour of Aviation Medicine on the Truhlsen-Marmor Museum of the Eye® app, available for free from Google Play and on the App Store.