Author: Aubrey Minshew, Museum Specialist, Truhlsen - Marmor Museum of the Eye®

In the late 1800s, there was a popular scientific belief that the last image seen by a dying person or animal was “recorded” on their retina. Therefore, if one could figure out the process, one could “develop” the retina like a photograph to show that image. It sounds fairly wild to the modern ear, but is this concept fact or fiction? Let’s take a closer look.

An image developed from a dead retina is called an “optogram” and the process is called “optography.” To a 19th century ear, this concept didn’t seem as far-fetched as it does today. Not only was our understanding of modern medicine still growing by leaps and bounds, but photography was an exciting new technology. In the public imagination, the eye and the camera became linked – for example, the eye and the camera both have lenses, and a camera aperture acts similarly to the human iris. In a time where new discoveries were being made every day, it wasn’t a wild idea to suggest that eyes might be able to permanently capture images like a camera too.

An early camera, c1905

Of course, scientists dove in to find out. In 1876, a physiologist named Franz Christian Boll discovered rhodopsin, a visual pigment in the retina that blanches in light but regains its purple hue in the dark. Boll called this “visual purple.” Next, another physiologist named Wilhelm Friedrich Kühne created a procedure that fixed the bleached rhodopsin in the retinas of dead rabbits by washing them in a solution of alum.

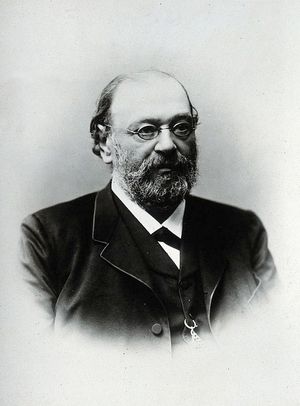

"Willy" Kühne

According to Kühne, the fixed rhodopsin could be photographed, allowing us to see where a creature or person was looking at the time of their death. The pattern in the image below is the first optogram Kühne produced. He claimed the image was of a barred window that a rabbit was looking at immediately before it died. Soon Kühne tried to apply this method to deceased human retinas, but without success.

Can you see the window?

Despite the questionable science, Kühne’s experiments quickly jumped into real world applications. Based off a fundamental misunderstanding of Kühne’s process, law enforcement in the UK (and eventually the US) tried to apply optography to criminal investigations. Unlike Kühne, who advocated taking “freshly dead” retinas and developing them in a solution of alum, “forensic optography” consisted of photographing a murder victim’s eyes and trying to identify their killer’s face from whatever patterns the photograph showed.

Even though this procedure is not scientifically sound, that didn’t stop forensic optograms from being used in famous criminal cases and from appearing on real trial records. In 1888, British police inspector Walter Dew wrote about a forensic optrogram from murder victim Mary Jane Kelly, hoping that the face of her killer, the infamous Jack the Ripper, could be identified in the picture. Over 25 years later, in 1914, a grand jury in the US admitted a forensic optogram as evidence in the case of the murder of twenty-year-old Theresa Hollander, although the boyfriend suspected of her murder was found not guilty.

A contemporary cartoon portraying Jack the Ripper, 1888

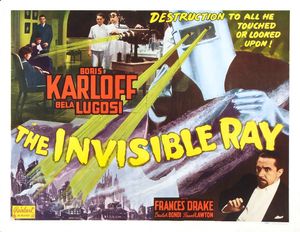

While forensic optography is scientific fiction, it quickly became a fixture in literature and media. Forensic optograms appeared in Jules Verne novels. They were featured in the 1936 film “The Invisible Ray,” starring Béla Lugosi and Boris Karloff. They also served as a plot point on the television show “Doctor Who.” In the end, it would appear that optography’s impact has been far stronger and longer-lasting in the world of popular culture than in the world of science.

This 1936 film features forensic optography