Positive Black Out

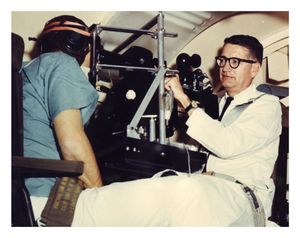

In 1951, Thomas Duane was stationed at the Naval Air Development Center - home of the Johnsville human centrifuge. The centrifuge had been installed the year before and was the world’s most powerful tool for studying the effects of g-forces on the human body. Pilots can black out while experiencing positive g-forces during flight. Duane’s study determined why this happened and documented “greyout,” when vision is dimmed, and peripheral vision lost before a pilot blacks-out or faints due to loss of blood pressure. Emil Bethke was then brought in to illustrate Duane’s findings. It would be 15 years before a fundus camera was mounted to the centrifuge to photograph the phenomenon.

Thomas Duane, MD (1917-1993)

The centrifuge remained in use for almost 50 years as part of training for pilots and astronauts. John Glenn recalled, “[In the centrifuge] you were straining every muscle of your body to the maximum…if you even thought of easing up, your vision would narrow like a set of blinders, and you’d start to black out.”

The centrifuge remained in use for almost 50 years as part of training for pilots and astronauts. John Glenn recalled, “[In the centrifuge] you were straining every muscle of your body to the maximum…if you even thought of easing up, your vision would narrow like a set of blinders, and you’d start to black out.”

Bethke's Retinal Illustrations

According to Duane, medical illustrator Emil Bethke spent only “about a week” with the study “but during that time rode the centrifuge time and time and time again, which was a huge undertaking in itself, until he finally was able to see the changes going on in the subject’s eyes.” Afterwards, Bethke produced nine illustrations for Duane.

According to Duane, medical illustrator Emil Bethke spent only “about a week” with the study “but during that time rode the centrifuge time and time and time again, which was a huge undertaking in itself, until he finally was able to see the changes going on in the subject’s eyes.” Afterwards, Bethke produced nine illustrations for Duane.