I first met Dr. W. Morton Grant in 1988 during the initial weeks of my glaucoma fellowship at Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary.

I was attending the weekly glaucoma research meeting, and Dr. Grant was sitting at one end of a long table, arms crossed, listening calmly to the group discussion lead by David L. Epstein, MD. The presenter went on for a while, with Dr. Epstein asking questions, and a point was raised that left the room silent. Dr. Epstein asked Dr. Grant to comment, and he responded with a question that brought the issue into clear focus.

W. Morton Grant, MD

I learned that this was typical for Dr. Grant — he would sit quietly and softly ask a question when directly asked to comment, and only seldom otherwise. Dr. Grant’s questions sounded simple yet were insightful and always led to the heart of the matter. His reserved manner only increased the weight of his words when he spoke.

Dr. Grant told me a story about a problem the astronauts were having in the early days of the United States space program. Shortly after reaching space, the astronauts would develop blurred vision, conjunctival hyperemia and tearing. NASA gathered experts, including Dr. Grant, and the group was having great trouble identifying the cause of this problem. Finally, Dr. Grant’s thoughts were solicited, and as was his wont, Dr. Grant asked a question: “How are the astronauts’ space suits cleaned?” It turned-out dry-cleaning fluid was used shortly before the suits were donned, and the solvent fumes were liberated in the capsule during flight.

The NASA episode represents a synthesis of some of Dr. Grant’s various interests, so let’s go back to the beginning. Dr. Grant was born July 23, 1915 to William and Vera Grant in Lawrence, Mass. He took what might be called a gap year — at age 13 – to teach himself chemistry and learn plumbing. It turned out to be time well spent. After graduating from Phillips Exeter with honors, he completed his bachelor’s degree at Harvard College in 1936 in three years. He was initially poised to pursue further studies in chemistry, but was persuaded by his father, a general practitioner, to study medicine. He graduated from Harvard Medical School in 1940. During his studies, Dr. Grant took an elective with David G. Cogan, MD at Massachusetts Eye and Ear that was a turning point in his life, resulting in his becoming an ophthalmologist.

Following internship at Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit, Dr. Grant followed an unconventional route to ophthalmology under the mentorship of Dr. Cogan and Dr. V. Everett Kinsey in the Howe Laboratory, Harvard, Massachusetts Eye and Ear — no residency, no fellowship. The world was at war, and as part of the national effort the scientists in the Howe Lab were tasked with finding treatments for mustard gas and other chemical injuries to the eye. Dr. Grant had the interests and background for this project, on which he worked with Dr. Kinsey.

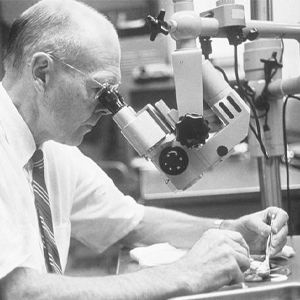

Dr. Grant at the microscope in the Howe Lab, studying a human cadaver eye.

Although the problem proved overwhelming, their efforts gave both men a wealth of knowledge and experience in toxicology and biochemistry and led to Dr. Grant’s encyclopedic work, Toxicology of the Eye, in 1962, with later editions in 1974, 1986, and 1993. One of the great privileges of my life was to work with Dr. Grant on the 1993 edition of his book. His patience, kindness and mentoring during this process were invaluable to my own development as a clinician-scientist and as a human being.

Dr. Grant, self-educated in ophthalmology, became American Board of Ophthalmology certified – a feat that was remarkable at the time, and would not even be possible today. He was the model clinician-scientist, taking clinical problems to the lab to return with greater understanding of physiology and pathophysiology, as well as clinical solutions.

Early on, Dr. Grant developed a relationship with Dr. Paul A. Chandler, a busy and thoughtful clinician and surgeon in Boston. Their morning meetings in Dr. Grant’s lab over coffee were the stuff of legend, where great problems in glaucoma were identified and discussed and studies planned and analyzed, often together with clinical and research fellows, other trainees and lab members. One of Dr. Grant’s greatest talents was his ability to explain complex concepts in simple terms, in ways that anyone could understand.

Dr. Grant’s clinical activities were mainly geared toward resident and fellow training. In addition, he frequently assisted Dr. Chandler in surgery. The trainees had a hotline to Dr. Grant in his lab on the fifth floor of the Howe Laboratory. When a call came in, Dr. Grant would quickly walk five flights of stairs to the glaucoma consultation service, which Dr. Grant directed 1960-1982 and confirm the history and pertinent portions of the clinical examination, particularly gonioscopy. He was meticulously attentive to detail, and often noted key findings that would guide the patient’s management.

Dr. Grant’s education of trainees was always provided with kindness and clarity. If someone missed or mistook a portion of the exam, such as the gonioscopy examination, Dr. Grant, arms crossed, might say something like, “Well, my gosh, I can see how you might think that angle was open, but if you look right here, the angle is occluded by the iris, and, oh, look at that, the iris is attached to the trabecular mesh work all the way around the eye.” He would say this sincerely, not sarcastically, as many of us may have experienced during residency or fellowship.

It was this clinical acuity that resulted in Epstein and Grant’s identification of heavy molecular weight (HMW) lens proteins as the cause of outflow obstruction in phacolytic glaucoma. A clinical observation by Dr. Epstein, confirmed by Dr. Grant, of cells moving slowly in the aqueous humor of patients with phacolytic glaucoma, as if in a viscous substance, led to experiments in the laboratory using ocular perfusion technology developed by Dr. Grant, proving that HMW lens proteins obstruct outflow and could cause this entity. This is also an example of Dr. Grant (and Dr. Epstein) modeling clinician-scientist behavior. They identified a clinical problem, took it to the laboratory, and proved their hypothesis providing a fundamental understanding of the etiology of this disease.

Drs. Schuman and Grant pictured in a conference room in the Howe Lab.

Dr. Grant developed tonography for the clinical measurement of aqueous outflow facility. In this procedure, a weighted Schiotz tonometer is placed on the eye and intraocular pressure is recorded over four minutes. The slope of the decay in intraocular pressure defines the outflow facility. At some point, Dr. Grant noted that the second eye tested often had a lower intraocular pressure than initially measured. He and Dr. Chandler puzzled this out, realizing that it was most likely evaporation during the 4 minutes the eye was open while the other was being tested that caused this.

Dr. Chandler; a Chesterfield smoker, used the cellophane cigarette pack cover over the eye to be tested while tonography was being performed in the first. They found that this solved the problem, and a plastic cover (no longer cigarette cellophane) is still used to this day on the contralateral eye while the first eye is being tested.

To measure outflow facility in the laboratory, Dr. Grant invented several tools and techniques. His seminal studies on aqueous humor outflow facility in enucleated human cadaver eyes elucidated the site of normal outflow resistance in the trabecular meshwork and abnormal resistance in glaucomatous eyes. His work defined the behavior of Schlemm Canal and the trabecular meshwork and their effects on resistance to outflow at different levels of intraocular pressure.

Dr. Grant and Dr. Chandler were highly respected as educators. They demonstrated not only a love of learning, but the values of inquisitiveness, integrity and ingenuity. Their series of lectures at the New England Ophthalmological Society resulted in their book, “Lectures on Glaucoma”, published in 1965. The second edition was titled “Glaucoma” (1985), and subsequent editions titled “Chandler and Grant's Glaucoma” (1985, 1996, 2013, 2021).

The book lives on as a case-based ‘approach to glaucoma’, integrating clinical patient care and fundamental physiology, pathophysiology, pharmacotherapeutics and surgical approaches.

Dr. Grant received many well-deserved accolades, including the Proctor Medal (Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology, 1956); Knapp Medal (American Medical Association, 1961); and Howe Medal (American Ophthalmological Society, 1968). He became the first David Glendenning Cogan Professor of Ophthalmology at Harvard Medical School in 1974.

Dr. Grant was honored with a Festschrift by his trainees at the New England Ophthalmological Society in 1990. The list of speakers was a who’s who of ophthalmology. In 1991, Dr. Grant became a visiting professor of ophthalmology at Tufts University School of Medicine. Dr. Grant’s and Dr. Chandler’s fellows honored their mentors with the formation of the Chandler-Grant Society (now the Chandler-Grant Glaucoma Society). This group promotes the teachings and life-lessons of Chandler and Grant, particularly integrity, honesty, lifelong inquisitiveness, humility, the priority of patients and kindness.

Dr. Grant provided a life example of the role of the clinician-scientist. His approach to the profession is not often seen today. Generous with his time and wisdom, he was always a gentleman. Rarely effusive, he had a dry sense of humor. His integrity was unparalleled. He disliked the spotlight; in fact, he rarely gave a lecture with slides.

Ironically, he did so when delivering the Robert N. Shaffer Glaucoma Lecture, later published in Ophthalmology as, “Why Do Some People Go Blind from Glaucoma,” at the Academy’s 1981 annual meeting and the slides failed to operate properly, disrupting his talk. It is said that he never again used slides in a lecture.

The story of the NASA astronauts demonstrates how Dr. Grant amalgamated his many talents to solve an important and difficult problem. It brought together his clinical acumen, his love of chemistry, his knowledge of toxicology and his skills as a clinician-scientist. All were tied together with Dr. Grant’s ever-present humility, speaking only when asked to comment after others had spoken.

Dr. Grant died at 86 in Winchester, Mass. on Nov. 17, 2001. His wife of 65 years, Jeanette (Poirier), died six weeks later. They left two sons, David and Jeffrey, a daughter, Jeanne G. Ancarrow of Richmond, Va. and four grandchildren. Dr. and Mrs. Grant are buried in Richmond near their daughter’s home.

Acknowledgements: This article was compiled from obituaries written by Joel S. Schuman, MD; David L. Epstein, MD; E. Michael Van Buskirk, MD; M. Bruce Shields, MD; Simmons Lessell, MD; Claes H. Dohlman, MD, PhD; and Evangelos S. Gragoudas, MD; and existing materials from the New England Ophthalmological Society’s W. Morton Grant, MD, Festschrift, March 16, 1990.