A man of great character, Edward W.D. Norton, MD (1922-1994) was a prominent 20th-century ophthalmologist who in the 1950s and ‘60s laid the groundwork for the Bascom Palmer Eye Institute at the University of Miami.

Principles

When Dr. Norton was asked to what he might attribute the success of the Institute, he provided a list of principles that he followed. These traits reflect the man. These principles are recast here.

Integrity was his prime principle. He demanded it of himself and others. No matter what other talents you might have as you applied for a training position or to join his team, you were not welcome if you lacked integrity.

Integrity encompassed selflessness, compassion, and a sense of obligation to the community — these became an infectious ethos that dominated the culture of the Institution.

Credibility meant having the facts before clinical and administrative decision-making. Fact-based confidence leads to predictable behavior. He was not arbitrary. He mentioned further, “Be organized: Have a plan with a vision of the outcome and an ability to balance priorities. During your implementation of decisions, back up what you plan; [then] move ahead.”

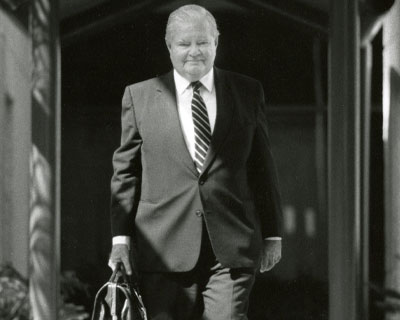

Edward W.D. Norton, MD

Develop key faculty and “let key faculty be the stars; don’t you try to be the brightest star in the universe.” Promote individual development: Tell each of them, “Be the best you can be.”

Flexibility to accept the eccentrics: “Don’t try to change them but adapt to the needs of individual faculty.” An offer to join the faculty started with details of what he, as chairman, would provide — an environment conducive to professional growth and success, an office, secretarial services, a laboratory, compensation, support of professional travel, etc. The next paragraph stated simply, “For your part, I expect you to become the best academic ophthalmologist of which you are capable.” It is important for the chairman to listen. You do not have to agree. Be genuine when you say, “I appreciate your opinion about this; I just don’t happen to agree.”

Dr. Norton’s eldest daughter wrote: “He had the rare ability to hold strong convictions while not being judgmental toward others who held different views.” She also commented that despite having so many things going on, when he conversed with you it was as if you were the only person on his mind.

Capacity to delegate. Issue both responsibility and authority. I remember a time early in my career when Norton and others were to be away, so he left me in charge. He told me that he doubted any decisions of import would arise, but if they did, I should decide whatever I thought best. He said that he might not agree with a decision, but when he returned, he would uphold it. I was pleased that he trusted me. Fortunately, no decisions of much import came up.

Be a caretaker: like a gardener, “Pick the plants, cultivate the flowers, watch the blooms.” He was ever so careful when choosing faculty, staff, and trainees. Then he nurtured them.

Loyalty to the institution: “Chairs and faculty may go, the department may change in strength, the Institution is forever.” Loyalty extended to the faculty. Once you were a member of his team, he would do anything to have you succeed. Professional travel was an opportunity for faculty members to attend and to speak at a symposium, to learn from other participants, to be heard and respected, and to enhance the Institute’s reputation. He was also loyal to the University, serving as interim dean of the medical school when the position became vacant in 1991, although he would rather have focused on Bascom Palmer.

Bascom Palmer was to be an Institution of the highest quality. The faculty invested in the Institute by donating any “excess” clinical earnings (after overhead costs and promised faculty salaries had been paid), rather than taking the “excess” as a bonus, which University policy would have permitted. The faculty were with him in making a first-class institute.

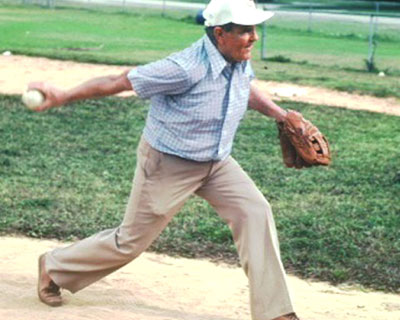

Dr. Norton loved baseball, here in a 1981 faculty vs. residents game.

Origins

Dr. Norton was born in 1922 in Massachusetts, from a family of Irish immigrants. He was a delicate child and was taken to warm beaches, sometimes in Florida. His mother died when he was 19. After graduating from Harvard College in 1943, Norton went to Cornell Medical School. He was inducted into the U.S. Navy and met Mary Knesnik, a student nurse. They married in 1945 and had five children. Dr. Norton was called to active duty and assigned to the Oakland Naval Hospital and later the port of San Diego, where Mary was able to join him. While there, he developed bulbar polio. When he recovered, he was assigned to complete his time on an ophthalmology service instead of sea duty on a destroyer.

Dr. Norton took 15 months of residency training in neurology before starting an ophthalmology residency at Cornell Medical College-New York Hospital. But illness struck yet again; he was discovered to have pulmonary tuberculosis, which required six months of hospitalization. He then completed his ophthalmology residency, and afterwards undertook 15 months of additional training in two fellowships in neuro-ophthalmology — one at the Wilmer Institute of Johns Hopkins University (Dr. Frank Walsh) in Baltimore and another at the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary (Dr. David Cogan) in Boston.

In 1954, Dr. Norton became an instructor in surgery (ophthalmology) at Cornell Medical College- New York Hospital. He was quickly recognized as the only person in New York City who could successfully repair a detached retina, using skills he had learned from Dr. Charles Schepens in Boston. In November that same year, Dr. Norton learned that a medical school in Florida was looking for a chief of ophthalmology, and by mid-1958 the Norton family moved to Miami.

Dr. Norton loved people. From childhood, his innate charm captured many classmate friends. He could strike up a conversation with a stranger, always talking about the stranger’s life and interests rather than his own. He was eager to learn about whatever area of knowledge he hadn’t experienced before. All were captivated by his charisma. Mary was of similar ilk, having gone into nursing because some of her high school friends had been casualties in the war. She was exceptionally popular, vivacious, outgoing, and joyful. She endured the hardships of being married to a man who responded to war time obligations, who met the demands of his medical education, and who faced illnesses and unexpected obstacles while he climbed to the top of his profession.

Dr. Norton and his family with their red Volkswagen van.

Chronology in Miami

Dr. Norton was offered a faculty position at the University of Miami School of Medicine as the full-time head of ophthalmology in 1958. The medical school was young, having graduated its first class in 1956. Miami had been growing since the end of World War II. Volunteer part-time faculty had established an ophthalmology residency with five residents at Jackson Memorial Hospital as the teaching hospital for the Medical School. Dr. Bascom Headon Palmer died in 1955 after serving for 20 years as a member of the University of Miami Board of Trustees. Palmer’s patients included the carriage trade, and he accumulated a fund to establish an eye clinic to provide “eye care for indigents and others, treatment and research, conservation of sight, and dissemination of information.” This coincided with Dr. Norton’s goals, and Dr. Palmer’s widow offered the fund to Dr. Norton, urging that the new institute be named for her husband.

Dr. Norton recruited additional faculty in 1959 beginning with his closest friend and confidant, Dr. Victor T. Curtin, a retina specialist, and a pathologist. Dr. J. Lawton Smith came in 1962 as a neuro-ophthalmologist. Dr. J. Donald M. Gass joined as a retinal specialist. The fifth ophthalmologist was the pediatric ophthalmologist, Dr. John T. Flynn. Two laboratory scientists, Thorne Shipley and Duco I. Hamasaki, came in 1963. As an upgrade to the residency program, Dr. Norton made himself personally available to the residents whenever they needed help with a patient, and he came to the operating room when the residents performed surgery. He instituted Saturday morning teaching conferences. Afterwards, all faculty and trainees, were welcomed to his home with their families for an afternoon picnic with swimming and games (especially tennis), as an informal social event. It was a close-knit community.

Dr. Norton immediately engaged the community practitioners. Many continued to teach residents as voluntary faculty and attended the weekly grand rounds on Thursday mornings. Norton also inspired them to social responsibility and teamwork. For example, he expressed concern about the long-term safety of newly developed intraocular lenses for implantation at the time of cataract removal. The immediate optical advantages were obvious to surgeons and patients, but Dr. Norton suggested not implanting more of them until the long-term safety was better known.

Dr. Norton suggested a community-wide moratorium, to be conducted and supervised by a committee of the community, not the Institute, and that a resident be assigned to examine each patient annually and report the results. He also established a policy that patients would be seen by the full-time faculty only by referral and would be sent back to the referring doctor after consultation or requested treatment. Drs. Norton and Curtin shared two small offices and an examination room in Jackson Memorial Hospital, using two operating rooms dedicated to eye surgery. Meanwhile, they used part of their private clinical earnings to air condition, clean, paint and upgrade the ward for Blacks in the racially segregated hospital. His biographer, John Flynn, commented that they knew they could not abruptly change the social culture of the time, but this much they could do.

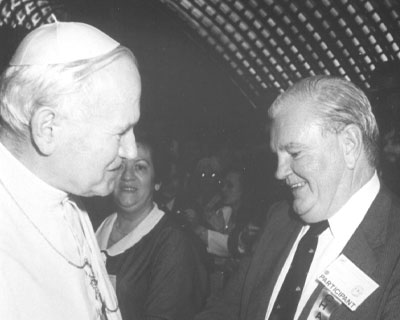

Dr. Norton received by Pope John Paul II in 1986.

The first building of the Bascom Palmer Eye Institute appeared in 1961. It provided offices, laboratories, and outpatient examination rooms. The faculty grew in number and flourished. Many became national and international leaders. Demand for clinical services expanded faster than could be met. Miami itself grew, especially with a major immigration from Cuba and later the rest of Latin America. As the Institute’s reputation grew, patients from all around the world were referred for consultation or specialized treatment. Today, there are 83 full-time ophthalmology faculty and 12 optometrists providing clinical care, and 19 full-time non-clinical faculty scientists.

The clinical training program now accepts 7 ophthalmology residents each year for 3 years of training (which along with two co-chief residents is 23 at any given time), plus 38 clinical fellows for extended training in subspecialties, as well as medical students taking an elective course in ophthalmology. There are in addition 6 optometry residents being trained by the optometric staff, and a number of students on rotation from various optometry schools. Early in the 1970s, the faculty had outgrown its space. In 1976, the second building of the institute opened on new land, the Anne Bates Leach Eye Hospital. The third building in the complex, the Edith and Earl Retter Education Center, was soon added. Of great importance to Dr. Norton was the library, later named the Mary and Edward Norton Library of Ophthalmology.

He maintained a subscription to nearly all relevant publications in any language. Major textbooks were purchased as they were published. As he traveled the world, Dr. Norton visited stores that carried used medical books and amassed a large collection, which included rare publications from previous centuries, now housed in a secure rare book room. The library was intended to be a resource for the entire community, including optometrists.

Dr. Norton himself became prominent in national and international professional activities and organizations. In the United States he had impact on the American Academy of Ophthalmology, the American Board of Ophthalmology, and the American Ophthalmological Society. Each organization called on him for help, as did the emerging National Eye Institute. Norton’s character, intelligence, selfless dedication, superb insight, negotiating skills, and administrative talent benefited all these enterprises.

The Later Years

One day, while in a reflective and pensive mood, Dr. Norton commented to a small number of us waiting for a meeting to begin, that he and most physicians were so devoted to their profession that they were not attentive enough to their families. He began to take off Mondays to spend with Mary, for lunch, going to a museum, or shopping. Now, their nest began to empty, there was no war, and the Institute was largely under control. Finally, they could spend some unhurried time to be together. Dr. Norton had always met each new obstacle or challenge in life with equanimity. For perhaps the first time in his life, he was overwhelmed when Mary died suddenly in 1980. His friends and colleagues grieved with him, and it was not too long before he was able to resume his leadership in the profession and at the Institute. And he learned to sail. Dr. Norton retired in 1991 leaving the Institute in the hands of others. In retirement, Norton travelled the world with longstanding friends. He enjoyed time with his children and his grandchildren with greater leisure.

“Sorry ... Dr. Norton is in consultation [his boat], and unable to come to the phone just now.”

Dr. Norton died in 1994 at the age of 72. Hundreds came to the church for his funeral —colleagues, patients, employees, and admirers from all walks of life. His family generously allowed others to come to say goodbye. An exceptionally strong afternoon thunderstorm, typical of the subtropics in summer, and which Dr. Norton had always loved, also attended the occasion. Its heavy tears delayed the start of the service for over an hour by preventing the casket from being brought into the church from the hearse.

Author’s Note: This biography is based in part on an extensive biography written by John T. Flynn, “The Chief: A Biography of Edward W.D. Norton, MD,” 2002. The book title reflects the fact that to younger colleagues, calling him “Ed” seemed too familiar. Calling him “Dr. Norton” seemed too formal and distant, so he was addressed by many as “Chief.”

Editor’s Note: We are grateful to our History of Ophthalmology editor, Daniel M. Albert, MD, MS, and his editorial assistant, Ms. Jane Shull, who contributed to the editing of this article.