At an early stage of my career, I performed and taught anterior segment surgery — particularly as it related to cataract. In teaching, I always stressed the importance of surgical ergonomics: positioning the patient in a way that maximizes their comfort and aids the surgeon.

Proper positioning of the recumbent patient enhances surgical exposure and helps alleviate patient anxiety; both make the surgeon’s task easier. If the surgical experience is good for the patient, it is likely to be good for the surgeon.

I often said to the learner, “Ergonomics is everything.” How correct I was. But in retrospect, how little I knew about the subject. I neglected the musculoskeletal impact of practicing ophthalmology and ophthalmic surgery, and the central role of ergonomics. Ergonomics (from the Greek words “ergos” and “nomos,” which respectively mean “to work” and “study of”) is far more significant and encompassing than simply positioning a patient for surgery.

The Board of Certification for Professional Ergonomists (BCPE) defines ergonomics as “a body of knowledge about human abilities, human limitations and human characteristics that are relevant to design. Ergonomic design is the application of this body of knowledge to the design of tools, machines, systems, tasks, jobs and environments for safe, comfortable and effective human use.”

Most ophthalmic diagnostic and surgical equipment has been designed without consideration for the comfort of ophthalmologists’ necks, backs, shoulders, arms, wrists and hands. Compared with family medicine practitioners, ophthalmologists are more than twice as likely to have neck pain, more than 2.5 times as likely to have hand/wrist pain and 3 times as likely to have lower back pain1. These disconcerting figures are likely higher in female than male ophthalmologists due to differences in physical stature and other factors. In a 2005 survey of roughly 700 ophthalmologists, 52% self-reported neck, back or arm pain, and 15% sensed that their work was affected by these symptoms2. Indeed, across multiple studies, at least 50% of ophthalmologists report chronic back and neck pain.

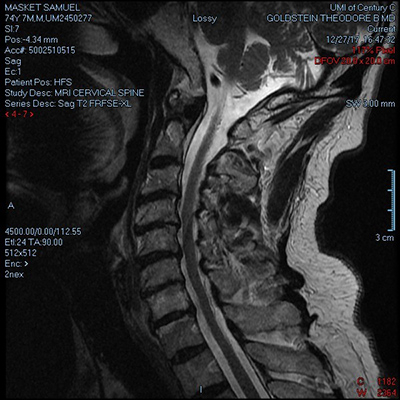

Figure 1. This MRI (lateral view) reveals. significant stenosis in the lower cervical spine.

Moreover, the incidence of symptoms increases with work volume and time. This is of considerable relevance to senior ophthalmologists (SOs), whose careers may be affected over time. Near the end of my surgical career, I experienced neck pain and finger numbness and tingling upon head turning. An MRI (Figure 1) confirmed disc and bone changes, along with moderate to severe multilevel cervical spine stenosis. Remarkably, the symptoms disappeared shortly after I stopped performing surgery. Other colleagues have related their stories in a variety of forums, most commonly in EyeNet. In a SO-sponsored Learning Lounge session on Ergonomics at AAO 2019 in San Francisco, the prolific anterior segment surgeon Steven Safran, MD, described his experience with horrific work-related neck pain that ultimately required cervical fusion (Figure 2).

Figure 2. This X-ray (lateral view) reveals the “surgical hardware” after cervical fusion in an ophthalmologist with severe neck pain.

Image courtesy of Steven Safran, MD

Suffice it to say that our profession places us at great risk for musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) later in life. However, the subject should be of even greater significance to our young colleagues. One might hope that increased attention to these concerns could prevent long-term physical harm and MSDs, allowing careers to be prolonged as desired rather than limited by physical ailment.

The Academy has had a long-term interest in physician wellness and ergonomics, particularly with regards to MSDs in ophthalmologists. Earlier, an AAO Task Force on Ergonomics was formed and led by Jeffrey L. Marks, MD, a vitreo-retinal surgeon at the Lahey Hospital & Medical Center who has published on the subject3 and has spearheaded the Academy’s efforts in this arena. A number of articles have appeared in EyeNet and there are annual courses and lectures on the subject.

That said, the message does not appear to have reached a sufficient base of the AAO membership. It appears that physicians have little interest in the matter until they are symptomatic. The good news is that there are now alternatives to traditional operating microscopes that stress our necks and backs. Industry, in general, seems motivated to develop ergonomic surgical tools to help reduce the likelihood of MSDs.

Awareness of the potential for physical harm is a good starting point for prevention. In a 2009 EyeNet article, contributing writer Linda Roach consulted with Academy members Jeffrey Marx, MD, Wayne Fung, MD, and Martin Wand, MD, to offer advice on risk factors for — and strategies to prevent — work-related injuries. In addition to suggesting stretching and motion exercises, the article proposed seven risk factors and potential solutions for MSDs in ophthalmologists, as noted below:

Figure 3. The custom design of this shortened slit-lamp table allows the examiner to get closer to the patient, reducing stress on the neck. Image courtesy of Steven Safran, MD.

Slit lamp

Stretching one’s neck into extension to reach the patient can be very stressful to the neck. Colleagues have modified slit lamp tables (Figure 3) to make it easier to reach the patient. Steve Safran, MD, has increased the length of the patient head strap to bring the patient and examiner closer to one another.

Figure 4. Poor posture at the operating microscope can affect the neck and spinal column.

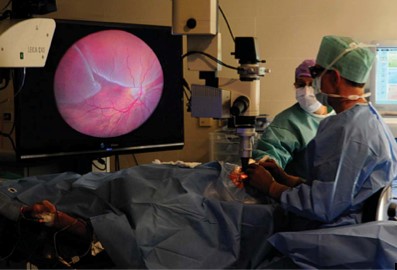

Operating microscope

Once again, stretching the neck and working in awkward positions can have deleterious effects on the entire spinal column, from neck to lower back (Figure 4). Traditional remedies include oculars that can be reclined at variable angles. Alternatively, the patient’s head can be turned toward the surgeon and the microscope further tilted to reduce neck strain during temporally oriented surgery4. More recently, there is interest in digital operating microscopes that don't require viewing through fixed oculars; rather, the surgeon views a large freestanding screen while wearing 3D glasses in what is called “heads up” surgery (Figure 5)5. Moreover, digital surgical microscope substitutes are now available with a virtual reality (VR) headset, freeing the surgeon from fixed oculars while not requiring surgical viewing of a remote screen.

Figure 5. During a “heads-up” surgery, a vitreoretinal surgeon views the screen while wearing 3D glasses rather than viewing through a microscope. This allows for an ideal operating posture (5).

Computer monitor screens

The physician’s neck and shoulders are potentially challenged while working at computer terminals. This effect is exacerbated while wearing bifocal spectacles, as they cause the user to extend their neck to bring the screen into the near-vision “sweet spot.” Ideally, one could use single-vision glasses aimed for computer distance or bifocals with the upper segment set for computer viewing.

Improperly adjusted chairs and tables in the operating room

Depending on the height and body habits of the surgeon and patient, the surgeon may sit in awkward positions that primarily stress their back muscles but may also stress their neck and shoulders. This is particularly true for temporally oriented procedures. During my surgical career, I always set the gurney, chair and microscope to match the patient’s anatomy to my position of comfort prior to the prep and drape. While those maneuvers added a few minutes to the surgery, I always believed that it was time well spent.

Microscope and machine pedals

Again, depending on the surgeon’s height and habits, it may be difficult to arrange the operating pedals in comfortable positions when operating temporally. This is most stressful on the lower back. Where possible, surgeons can evaluate several operating room table designs to best fit their anatomy. Some foot pedals have variable tilts or may be elevated on lifts as necessary.

Computer keyboards

The wrists and forearms are particularly vulnerable to fatigue and damage if the keyboard and mouse are not placed at the proper height and working distance.

External contact stress

Working with a hyperextended wrist can stress tendons and induce pain, numbing or tingling when tendons are stressed when working with a hyperextended wrist. This may also occur if the hands, wrists or arms come into prolonged contact with edges of the tables or other equipment. Padding and proper positioning may obviate these concerns.

Figure 6. Indirect ophthalmoscopy with the patient erect is particularly onerous to the physician’s back, neck, arms and hands.

In addition to the risk factors listed above, ophthalmologists place their bodies in uncomfortable, strenuous and risky positions when performing other tasks such as indirect ophthalmoscopy with the patient erect (Figure 6), minor surgical procedures and contact lens exams at the slit lamp and office-based intraocular injections. Moreover, training new surgeons at the microscope can place severe physical stress on the observer or supervisor.

There is a shifting demographic among AAO members, as we note a “greying” of the Academy along with the aging of physicians and society in general. Consider the following:

Academy SOs older than 60 years account for approximately 40% of AAO membership;

About 25% of U.S. physicians are 65 years old or older.

Ophthalmologists are working longer than ever and adhering to the concept that “60 is the new 40.” For that reason, among others, physical health and physician well being are of paramount importance.

The good news is that increased awareness of the impact and incidence of MSDs on ophthalmologists has led to action across several fronts. Industry has demonstrated keen interest in the subject by redesigning workspace products, such as improved stools, and by developing tools for “heads up” surgery. New microscope concepts can be expected to help save the necks and backs of eye surgeons.

Moreover, the Academy has shown interest in resurrecting the now-inactive Ergonomics Task Force and there are plans for the SO and Young Ophthalmologist (YO) Committees to collaborate on a variety of seminars and educational opportunities.

Additionally, ophthalmology residency programs through the Association of University Professors in Ophthalmology (AUPO) can consider adding ergonomic and wellness concerns to the teaching curriculum. There is a clear need to involve young members of the Academy in the development of a comprehensive ergonomic program that will benefit all age groups.

REFERENCES:

1. Kitzmann A.S. et al. Ophthalmol. 119, 213-220 (2012)

2. Dhimitri K.C. et al. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 139, 179-181 (2005)

3. Marks J.L. Ophthalmol. 119, 211-212 (2012)

4. Wallace B. R. J Cataract Refract Surg. 25, 753-762 (1999)

5. Eckardt C. and Paulo E.B. Retina 36, 137-147 (2016)