I’ve known my dear friend Eve J. Higginbotham, MD since 1986, when we met as I was completing my second year of fellowship with Drs. Morton F. Goldberg, Gholam Peyman and Maurice Rabb at the Illinois Eye and Ear Infirmary.

Dr. Higginbotham came in for an interview after completing her fellowship at the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary, and Eve was on my schedule. We spoke for more than hour in my small office and emerged with smiles and laughter. The secretary sitting outside of the interview room was curious when we stepped out.

“Do you two know each other?” she said.

Eve and I laughed and replied, “No, we just met today!”

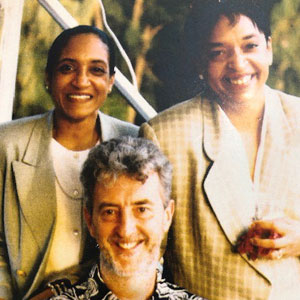

Left to right: Drs. Marcia Carney, Higginbotham and Thom Zimmerman enjoy an afternoon on a boat ride at ARVO in the 1990s.

It was like meeting a best friend later in life. We hit it off like sisters in secrets. I later met Dr. Higginbotham’s childhood best friend, Odile, in New Orleans who became like family as well. This was the beginning of a decades-long friendship, which included shared scholarship and yearly opportunities to room together at annual meetings of the Academy and the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology (ARVO).

Dr. Higginbotham grew up in New Orleans, the youngest of three daughters of parents who were both dedicated educators in the Orleans Parish School System at the end of the Jim Crow era. To this day, she remembers the impact of that period on her daily life. Experiences, such as waiting for her pediatrician in a small dimly lit waiting room are early memories. She always wondered why she was not able to sit in the larger, sun swept room instead. Although she does not remember what her parents told her as an explanation, she knew then that it was a question that was not worth repeating, because the answer always seemed beyond her reach, and significant societal changes were not on the immediate horizon.

Fast forward to her more recent days sitting in class in the Law School at the University of Pennsylvania, and she was reminded that the Hill Burton Law required construction of medical facilities that were segregated, and the memories of early childhood revealed themselves once again. The answer that she could not even imagine as young child was that our government mandated that certain groups would be segregated.

Although her life experienced beyond the shelter of her home delivered different messages, she learned from her parents to remain confident in her own abilities and understand that any racism she encountered was based on the ignorance of others and not a reflection of her own talent. Of course, growing up in the 1960s and 1970s and witnessing the egregious actions that occurred in response to protests during the civil rights movement clearly influenced Dr. Higginbotham’s career choices and professional interests during her entire life.

Dr. Eve Higginbotham meets one of her idols, the late Rep. John Lewis at Harvard’s graduation, when the congressman received an honorary degree and Dr. Higginbotham served on the Board of Overseers in 2012.

One year before the passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964, Dr. Higginbotham, along with two other African Americans, integrated a Catholic elementary school. It was a school she and her mother had walked past every day to attend a segregated black elementary school in New Orleans, where her mother taught fifth grade. She remembers her first day of school, when she walked from the church where Mass had been held to start the new year at the school. The sidewalk was aligned with adults. It is hard now for her to remember whether it was a protest or a supportive effort but being surrounded by so many adults was memorable.

Her parents took her out of that school after that year, noting that her shoes were never dusty when she returned home. It was an indication that she did not play at lunch, which was not an experience that her parents wanted to repeat a second year. Therefore, her parents took her out of St. Stephens Catholic Elementary School, and she returned to McDonough No. 6, followed by S.J. Green Junior High School and then McDonough No. 35, all segregated sanctuaries filled with fond memories and the roots of lifelong friendships.

Dr. Higginbotham returned to an integrated setting for high school, attending Benjamin Franklin Senior High School in uptown New Orleans. Her experiences from that one year in elementary school prepared her for an existence of often feeling isolated and the persistent need to exude excellence. Her work ethic intensified during these years. Franklin High School prepared her well to compete at institutions like MIT and Harvard Medical School. She always loved science and completing undergraduate and graduate degrees in chemical engineering at MIT cemented a love for discovery that continued throughout her career.

Her time at MIT went quickly, initially choosing chemistry as a major then switching to chemical engineering. Years later, one of her classmates who majored in chemistry, noted the significant level of gender bias in that department. When asked, Dr. Higginbotham cannot recall whether the culture of chemistry was a factor for her own decision to choose chemical engineering. Still, what she found in engineering was a highly collaborative and diverse community of budding engineers who shared her love for solving problems. Spending hours studying in the 24-hour school library on the top floor of the Stratton Student Center, she realized her experiences at MIT were preparing her exceptionally well for her future career interest in collaborating with others and a career in research.

Drs. Eve Higginbotham and her husband Frank Williams visiting Singapore in 2017.

Her first job interview at Procter & Gamble in Cincinnati convinced Dr. Higginbotham that staying in academia aligned more closely to her core passion for science and a life of discovery. Somehow, the prospect of a career in food engineering in corporate America did not capture her sense of purpose for scientific discovery. Thus, she decided during her fourth year to stay at MIT and complete her master’s in chemical engineering. During that pivotal year, she applied to both graduate school in chemical engineering and medical school. Although her sister, Edith, had already matriculated in medical school, she was not well-acquainted with the life of a physician scientist. Nevertheless, despite gaining admission to the University of California at Berkley to do graduate work in thermodynamics, she stayed in Boston and attended Harvard Medical School instead. Always a pragmatist, she considered her primary reason for attending medical school was to ultimately land in biomedical sciences, and have her clinical skills sustain her career if grants were not forthcoming.

Harvard Medical School was very different from MIT. There was more memorization and no open book exams. There was also little opportunity to study with fellow classmates. Her new experiences of caring for patients, learning a new professional language, and applying the literature to patients seen on the wards, kept Dr. Higginbotham focused on understanding this different world and the new norms.

Mentors and role models are important for any inquisitive student at any stage of life. A memorable mentor emerged during Dr. Higginbotham’s junior year, Dr. Mathea Allansmith. Dr. Allansmith exhibited all of the values and professional acumen that Dr. Higginbotham also aspired to achieve, including deep curiosity, love for research, clinical expertise, and a balance of work life and family. It was Dr. Higginbotham’s relationship with Dr. Allansmith that inspired her to seek a career in ophthalmology. Ophthalmology was the perfect discipline for meeting her goals of teaching, research, and patient care. Indeed, it was during the year that she worked in Dr. Allansmith’s laboratory, that she wrote her first peer-reviewed scientific paper, an accomplishment that fueled her academic interests for many years to come. Her positive experiences with Dr. Allansmith sealed her lifelong interest in ophthalmology.

As Dr. Higginbotham pondered her choices for a residency, she considered all available, remarkable potential opportunities. Since she had been in Boston for eight years, she decided it was time to return to her hometown of New Orleans. Always inquisitive about other parts of the country, she completed her internship at the Pacific Medical Center (now known as California Pacific Medical Center) and then returned home to complete her residency at the LSU Eye Center, spending the majority of her clinical time at Charity Hospital. These two stops in her career introduced her to four giants in the field, Drs. Bruce Spivey, Robert Stamper, Herbert Kaufman, and Thom Zimmerman. Caring for patients at Charity Hospital in New Orleans also introduced her to the disparities in health care that exist in the United States. Although she was not focused on public health at this time in her career, her experiences caring for poor patients would impact her for years to come.

Based on her positive interactions with Dr. Thom Zimmerman, the glaucoma faculty member at LSU Eye Center, and what appeared to be a frontier for greater research, Dr. Higginbotham decided on a career in glaucoma. She yearned to get back to doing research. A fellowship at Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary provided her with the perfect mix of research and patient care.

It was also the first time she had the opportunity to work with an ophthalmologist of color, Dr. Tom Richardson. Spending two years in his laboratory and seeing patients with Dr. Richard Simmons were elements of the necessary preparation for a productive academic career. For those ophthalmologists who did not train during this era, it was a time when, at least in Boston, glaucoma specialists sometimes did full thickness filters. This procedure was often associated with complications, such as kissing choroidals, flat anterior chambers, and thin, leaky blebs. Thus, the first few years of her career in this field sometimes required sleepless nights and late evenings returning home, caring for patients who sometimes developed these complications.

Dr. Higginbotham’s first position was at the University of Illinois. Although it was her only job offer, it was the best position for her. It is where she met me, and where we both were mentored by Dr. Morton Goldberg. Dr. Higginbotham often shared with me her positive experiences with Dr. Goldberg, whom she viewed as a highly inclusive leader, a generous intellectual sponsor, and clearly brilliant. He gave her a positive template for how best to lead a department, providing her with outstanding lessons that she would carry over to her own tenure as Chair and Dean, later on in her career.

Drs. Frank Williams and Eve Higginbotham on the golf course at Torrey Pines in 2010.

After spending her first few years at the Illinois Eye and Ear Infirmary, she was recruited to join the faculty at the University of Michigan. Her time there was also well spent, serving in the role as Assistant Dean for Faculty Affairs and learning process improvement methodology. During this time, she also served on the Board of Trustees of the American Academy of Ophthalmology. She was among the first women to serve on the Academy’s Board and the first woman of color to serve, an experience that further opened her eyes to the importance of good governance and policy. At both the University of Illinois and the University of Michigan, Dr. Higginbotham was active in National Eye Institute - supported clinical trials, the Fluorouracil Filtering Study, the Advanced Glaucoma Intervention Study, and the Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study (OHTS). OHTS emerged as a highlight of her career for the next 20 years, a study where she served as one of the Vice Chairs with Drs. Dale Heuer and Richard Parrish and also a member of the Endpoint Committee. Dr. Michael Kass, the Principal Investigator of OHTS and Dr. Mae Gordon, the Chair of the Coordinating Center, along with the Vice Chairs remain her friends and colleagues to this day.

University of Maryland Dean, Donald Wilson appointed Dr. Higginbotham as the first university-based woman chair of ophthalmology. It is interesting that both Dr. Wilson, an internist, and Dr. Morton Goldberg had been classmates at Harvard University years earlier. The department that she inherited was small and challenged, having lost a number of its senior faculty and commercial patients. Leaning on her core values and lessons learned from previous leaders with whom she interacted during the first few years of her career, she recruited new faculty, consolidated the clinics, eliminating the two-tier system of care that had previously existed, and brought clinical trials into the department. She led the department for 12 years, after which she decided it was time for higher academic perches to impact the House of Medicine still further.

Dr. Higginbotham was hired by former Surgeon General Dr. David Satcher, the director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, as dean of the Morehouse School of Medicine. After nearly four years, she was recruited to be the senior vice president of health sciences at Howard University, overseeing Howard University’s hospital, clinics, and schools of medicine, nursing, and dental medicine.

Dr. Eve Higginbotham is currently the inaugural Vice Dean for Inclusion and Diversity for the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, a position she assumed on August 1, 2013. Her work has already resulted in more than a 50% increase in the number of underrepresented faculty since arriving at Penn medicine in 2013.

A practicing glaucoma specialist at the University of Pennsylvania, Dr. Higginbotham, has authored or co- authored over 160 peer-reviewed articles and co-edited four ophthalmology textbooks She continues to remain active in scholarship related to glaucoma, health policy, STEM, and patient care. She recently became more active in lecturing and writing about social justice, currently leading an institutional effort at Penn medicine to address structural racism in the workplace and community.

The strategic initiative that she is leading entitled Action for Cultural Transformation (ACT) aims to make sustainable changes across all three missions of education, research, and patient care. This grassroots effort spans six hospitals in the system and the Perelman School of Medicine, including over 170 focus groups and 5,000 voices in the process. The plan is to map the course of this work over the next five years, transforming Penn medicine into a united, antiracist, inclusive and diverse community.

In her spare time, Dr. Higginbotham and her husband, Dr. Frank Williams, enjoy playing golf, Before the pandemic, they spent time playing golf, and traveling to locations around the world. Her husband enjoys working on his culinary skills, which of course, Dr. Higginbotham especially enjoys.

Dr. Higginbotham’s multi-decade career in ophthalmology has taken her beyond the field to positions where she has impacted the care of patients across the country. She serves on the Board of Ascension, the second largest health system in the country with a clinical presence in 20 states and DC. The one thing that remains constant is her love for caring for patients with glaucoma and interacting with her ophthalmology colleagues. Although the arc of her career has been broad, it has remained grounded in her love of science, discovery, collaboration, and service.

Our friendship remains at the core of both of our careers.