A swerve is an accident in history; a situation where the historical event is not based on obvious social, political or economic factors. Sometimes, such a swerve begins with an eye injury. We can use our understanding of eye disease to analyze the mechanisms of an eye injury that initiated a swerve with enormous effects, remote in time and distance.

1066: The Battle of Hastings. Most English historians, Churchill included, consider the Battle of Hastings as the watershed moment that defined England and, by extension, the English-speaking peoples. William the Conqueror won the battle and established the Norman conquest of England.

This victory would have far-reaching implications for England, including language, culture, politics, economics, and most particularly, our current system of jurisprudence. Insofar as history is written by the winners, every Oct. 14 the English celebrate this great victory by William the Conqueror, acknowledging this watershed event.

On the other side, Harold Godwinson, King of England, lost it all. But the battle almost went very differently.

Harold was a powerful earl, a member of a prominent Anglo-Saxon family, and elected to the English crown upon the death of Edward the Confessor. Two years earlier, Harold was shipwrecked off the coast of France and eventually found himself as the guest/prisoner of William, then Duke of Normandy and subordinate to the King of France. William released Harold, but only after exacting a promise from Harold that he would give William the rights of King of England.

It was a hollow promise, unlikely to have any meaning years later, especially as Harold was not in the direct line of succession for the crown. But William proved prescient. The assembly of the kingdom's leading notables, convening after King Edward’s death, chose Harold as the successor. Harold resolved to keep his kingdom. The Anglo-Saxon version of events depicts Harold as heroic.

Dr. Alfredo and Debra Sadun in front of the

Bayeux Cathedral, Normandy, France

On becoming King, Harold was challenged in two directions. William, in France, had spent over seven months in preparing to invade England by assembling over 700 ships (most of them Viking longships) along the coast of Normandy. William used Harold's promise to gain the support of French nobles along with that of the church, though it was probably the promises of spoil and land that increased his army of mercenaries.

Harold assembled his Anglo-Saxon troops and awaited the invasion off the coast of Southern England for over six months. Taking advantage of Harold being pinned down on the southern coast of England, another Harald (Hardrada) of Norway, invaded with over 300 larger Viking longships from the north. After initial successes, Norwegian Harald was finally met, on Sept. 25, by Harold of England, who had raced with a small army over 200 miles in a little more than four days to confront and defeat the Vikings.

By coincidence, this is when William finally launched his invasion from France, striking the south of England. Harold immediately force-marched his exhausted troops back south and tried to surprise William before the latter could prepare for the attack. There are no reliable records of how many soldiers participated.

William attacked Harold on Saturday morning, Oct. 14, and the battle continued all day. William had more cavalry and the English had more infantry. The battle flowed, to and fro, but it was mostly a stalemate: large numbers of infantry can use a shield wall to hold off cavalry, although they are also at a loss of mobility for any complicated maneuvers.

Such a stalemate, at the end of the day, would have favored Harold, for he could expect reinforcements in the morning and thereafter. William’s forces were fighting for spoils, and they would have likely returned to France if the fighting became harder. Harold’s forces were fighting for survival.

The battle raged for about nine hours. Although there is controversy as to how exactly Harold died, it occurred at about sunset, and his death led to the sudden disarray and defeat of the English forces.

Well-armored knights on horseback were almost invulnerable. Their heavy armor absorbed arrows, missiles and even spear thrusts from the infantry. But there were a few “chinks in the armor”. One such chink was the area of the eyes that sat below the helmet or behind eye slits.

Astride a horse, with his sons and other knights by his side, Harold would have struck down those who dared approach. Harold, like most of the Anglo-Saxons, favored the battle axe.

But sitting tall in the saddle, Harold attracted the attention of many archers. Most arrows would have bounced off his armor, a few sticking to his shield.

And then one penetrated into his right eye. Of course, there is no definitive description of Harold’s death. Guy, Bishop of Amiens, describes Harold as killed by dismemberment by four knights. Twenty years later, Amatus of Montecassino wrote that Harold was first shot in the eye with an arrow.

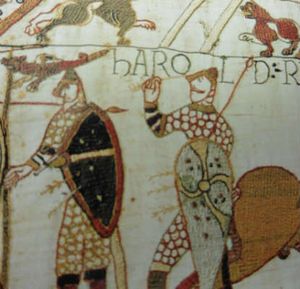

The best description was probably pictorial. The Bayeux Tapestry is a 230-foot-long embroidered linen cloth (technically, not a tapestry), commissioned to be made after the Battle of Hastings and now found in a museum in Bayeux, near the coast in Normandy, France. It shows the Norman conquest of England in a long series of frames. So, we traveled to Bayeux and found the museum near the gothic cathedral

The Bayeux Tapestry might be regarded as Norman propaganda. The Bayeux Tapestry emphasizes Harold’s ingratitude towards William who had befriended him. This is obviously meant to provide a moral justification for William’s invasion of England. The tapestry starts with depictions of how Harold was saved by William who personally paid his ransom to obtain Harold’s freedom. There are delightful scenes that show Harold and William going off to fight, shoulder to shoulder at Mont Saint Michel, where Harold heroically saves Williams men from quicksand. It also highlights Harold taking an oath to William. The tapestry documents how Harold left France obliged to William.

But most importantly, the tapestry details illustrate the Battle of Hastings in many panels concluding after Harold pulled an arrow out of his right eye.

Taken all together, we can use the Bayeux Tapestry in conjunction with various texts to make a reasonable medical conclusion. It seems likely that Harold took an arrow to his right eye and then shortly after removing the arrow, he collapsed and fell off his horse. The arrow struck near the eye but probably did not pierce the globe itself.

Often, the cornea and sclera give enough resistance for the eye to deform and slide out of the way. But if a sharp projectile passes into the orbit on the medial or inferior sides, the walls of the orbit channel it to the orbital apex. In the case of Harold, the arrow probably traveled to the orbital apex, and continued to be funneled back through the superior orbital fissure, and into the cavernous sinus where it encountered the carotid artery.

The tip of the arrow may have even lodged into the temporal lobe of the brain, but this further injury would have been of little consequence. If the initial penetration wasn’t enough, pulling out the arrow would have exacerbated the extensive bleeding from the carotid artery. Harold would have hemorrhaged extensively of much of his blood supply.

A minute or two later, Harold would have fallen off his horse. Then, all the armor that had protected him throughout the day would have become the instrument of his demise. Weighing over 100 lbs, the armor would have prevented Harold from standing up, much less permitting him to parry off the blows from his foes.

As the Bayeux Tapestry shows, and consistent with both the texts of Guy and Amatus, four knights then attacked Harold from different directions and hacked at his torso and limbs. This gruesome dismemberment probably did not produce more pain, as Harold was by now unconscious from all the blood loss.

With Harold dead, his sons tried to flee, and the army, already exhausted by forced marches up and down the length of England and a nine-hour battle, finally broke. The sun set on Norman knights on horseback chasing and striking down remnants of the Anglo-Saxon army.

Bayeux Tapestry scene that depicts Harold pulling an

arrow out of his right eye. Note the other

arrows in his shield.

The implications are far reaching. England went from Anglo-Saxon to Norman with a new language and customs. Together with influences from the church, England was now bound to the continent, to the crusades, and to many parts of medieval culture. But the tension between the line of Norman kings that followed and the barons of the land would create a unique governance, one that limited the king’s power.

The Magna Carta, written over a century later, would manifest more than create the concept that in England there were limitations to the king’s power. This document evolved through a complex set of precedents, to laws that tried to balance the conflicting interests of different parties, leading to an entirely different legal system from the continent.

Not Roman law, not Napoleonic law, but English common law would become the basis of our complex set of laws in the United States. From trial by a jury of your peers, to case law taking precedence over philosophical principles, our culture and system of jurisprudence largely dates itself to when King Harold was mortally wounded by an arrow to his right eye.