In his delightful musings about physicians’ roles on the stage of life (Winter 2015 Scope, “Life Is Not a Dress Rehearsal”) Bill Tasman included the 16th century French military surgeon Ambroise Paré, who has held a special interest for me since medical school days in the 1960s.

In his delightful musings about physicians’ roles on the stage of life (Winter 2015 Scope, “Life Is Not a Dress Rehearsal”) Bill Tasman included the 16th century French military surgeon Ambroise Paré, who has held a special interest for me since medical school days in the 1960s.

One of my general surgery textbooks began with the well-known quote from Paré, “Jele pansay, Dieu le guarit,” which translates to something like, “I treat, God heals.” That struck me as an appropriate reminder for humility (of which all surgeons can use a healthy dose) and caused me to wonder about the man behind the saying.

He was born in 1510 in the city of Laval and was raised in humble means as the son of a cabinetmaker. It was a time when surgery was beginning to emerge from the dark ages. During the 14th and 15th centuries in Paris, there were three classes of those who cared for the sick. Physicians were of the educated, elite class who limited their practice primarily to medicines and advice. At the other end of the spectrum were barbers, who had minimal education and traveled about performing their rather barbaric and primitive surgical procedures, usually at the advice of a physician.

Between these two classes, and unique to Paris, was the brotherhood of surgeons, who had quasi academic credentials and preferred medical treatments, but practiced some procedures such as applying cauterizing irons to inflamed or bleeding wounds. At the dawn of the 16th century, the latter two classes merged into barber-surgeons, and it was into this profession that Paré entered as an apprentice.

It was also a time when France seemed to be in perpetual military conflict, and this provided Paré with a practical laboratory in which to experiment with new techniques of wound healing.

After his apprenticeship, he became a military surgeon and soon found himself engaged in battle at the siege of Turin. A commonly held dogma of the day was that gunshot wounds were poisoned by the gunpowder and had to be detoxified with boiling oil, often making the treatment worse than the original condition.

In the heat of battle, Paré ran out of oil and decided to try a bland, soothing lotion of egg yolks, oil of roses and turpentine. This was a radical departure from the standard of practice, and the young surgeon knew his career would be over if his patient died of gunpowder poisoning. To his relief, the patient not only survived, but fared far better than those treated in the traditional manner, ushering in a new era of gentler treatment for wounds.

Another common practice of the day, which Dr. Tasman noted in his article, was the use of a hot iron to cauterize bleeding vessels in amputations. To this traumatic procedure, Paré added his gentle touch by advocating the use of ligatures to tie off major vessels, as was being used by some surgeons in treating ordinary wounds. Ocular injuries were also common on the battlefield, and Paré contributed to the early profession of ophthalmology by designing an ocular prosthesis, which was held in the empty socket by an iron wire wrapped around the head.

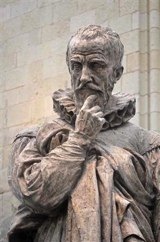

In his long career, Paré served as surgeon to four French kings and wrote numerous volumes that became the standard of French surgery for decades to come. He became a wealthy man, but is most remembered for his gentleness, compassion, honesty, devout Christian faith and a profound belief in the value of human lives.

As to the quotation for which Paré is credited, that apparently appeared first in the last sentence of his preface to The Method of Treating Wounds made by Arquebuses, and was repeated frequently in his clinical case reports as a reminder for humility.

During my fellowship at Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary in the 1970s, I attempted calligraphy of the saying and began giving framed copies to my glaucoma fellows when they graduated from Duke and later to the residents and fellows at Yale. I know that some of them have hung the quotation in their offices, and mine now hangs in my study at home. It reminds me of several things: of the pioneers, like Paré, who taught us the principles of surgery, including the gentle handling of tissues; of the awesome privilege that each of us have enjoyed in our surgical careers; and of the need to keep our role in the art of healing in proper perspective.