Harold Scheie the ophthalmologist and Harold Scheie the human being often overlapped, and it is hard for a son to say where one left off and the other began.

When the chips were down, he was both.

In a certain sense, my father was a magician. He could relate the modern to the past, the past to the modern, even the rural to the urban, the medical to the lay.

At the height of the tumultuous 1960s, when some parents were complaining about “free love,” marijuana and the rest of it, he could relate their challenges to those he faced growing up in the 1920s. Born in 1909, he came of age during Prohibition, learning to drink when it was illegal and gangsters were popular heroes. Instead of being shocked by marijuana (as were many younger parents at the time), he told me that it grew everywhere when he was a kid, that he had tried it and thought it was a waste of time. At the time, none of my friends’ parents shared that kind of perspective.

My dad’s nature was rural. He grew up in the Dakotas and northern Minnesota frontiers, which included living eight years on the Fort Berthold Indian reservation. The reservation was home to the Three Affiliated Tribes: Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara Nation. His family did business with the Hidatsa Chief “Drags Wolf” — a man described by Franklin Roosevelt thusly: "This man Chief Drags Wolf is a wise old man if he only could speak English. ... Oh, what he could do for his people as a great leader of the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation."

Among my father’s earliest memories were seeing an electric light bulb for the first time and seeing Indians cross a river that was too deep for their horses to wade through: They grabbed hold of the horses’ tails, slapped the horses on their butts and hung on while the horses swam across. Later, my grandfather (who preferred horses) bought a Model T Ford and accidentally drove it into the river, where it promptly sank out of sight. Contemplating this fiasco, my grandfather exclaimed, “No horse would ever have done that!”

Among my earliest memories was meeting my grandparents: Lars Tobias (“Toby”) Scheie and Ella May Ware Scheie. They were very different from one another. Toby was a hard drinking, plain-talking man with a legendary sense of humor. Ella was a Puritan, teetotaling member of the Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), a no-nonsense woman who, starting at the age of 16, raised her brothers and sisters after their mother died and their dad left. She was a local midwife who delivered her own children as well as those of friends and neighbors. My dad’s interest in medicine seems to have been in his genes.

Dr. Scheie pictured at age 13 with his pig, which won a prize in a statewide contest.

The Scheie family moved to Minnesota, eventually settling down on a farm near Warren. Life was primitive, without running water, and the winters fearfully cold. In the winters, they held on to the wires which ran from the farmhouse to the outhouse and barn buildings to avoid getting lost and possibly dying in blizzards so blinding that it was impossible to see a hand in front of a face.

It was during his childhood that my father developed his lifelong work ethic and habit of rising at ungodly hours. Many a resident used to tell me of how they would arrive for surgery shortly after 6 a.m., and my dad would snarl, “Good afternoon!” To say that he was a workaholic would be an understatement. Early in the Great Depression, when the Midwestern banks went broke, the family lost their entire savings, and my dad had to work innumerable jobs for college money. One of them was with a butcher, who, noting my dad’s talent with a knife, pleaded with my grandparents not to let him go to college, saying, “You’ll be ruining the best butcher this town has ever seen!”

At the University of Minnesota, he distinguished himself as an athlete and played varsity basketball for the Minnesota Gophers. At 5 foot, 8 inches tall, he was known as “Shorty Scheie.”

Beginning with college and on through medical school, he worked as a waiter, movie theater usher, anything he could get. At one point, working three jobs in addition to carrying a full load of courses, he assisted in an autopsy of a man who had died of pneumonia. He then fell ill himself with type III lobar pneumonia and ended up in critical condition in an oxygen tent. It was untreatable at the time, and the last thing my dad remembered before losing consciousness was one of his favorite professors — Hobart Reimann, MD — bringing to his bedside a tray full of dead mice, which he had injected with my dad’s bug. Apparently, Dr. Reimann thought my dad’s scientific curiosity would be aroused. Fortunately, he recovered from that incident and from the pneumonia.

A close mentorship and friendship developed between my father and Minnesota medical school dean Elias Potter Lyon. Encouraged to rise to his potential, my father eventually decided to pursue his internship (which led to a residency in ophthalmology) at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. Arriving with a few dollars, he felt very much like the unsophisticated country boy he was, and it didn’t help much that Philadelphia in those days was a very snobbish place. When at first he inquired about an internship at the prestigious old Pennsylvania Hospital, he was sarcastically asked, “Did your ancestors arrive on the Mayflower?” This caused much laughter at the time, and throughout his life in Philadelphia my dad was always thought of as a country boy of immigrant stock.

Another new arrival to Philadelphia who became a lifelong friend was “Jimmy” the hippopotamus, who like my father had arrived in Philadelphia in the mid-1930s. As my father had to work long, long hours, the only time he could find off was Sunday afternoons. Without many friends at the time, he’d go to the Philadelphia Zoo, where he befriended Jimmy, who struck him as lonely. Every Sunday my father would treat him to apples and similar treats. Being used to animals as a farm boy, my dad was nevertheless surprised to discover that a huge wild beast could be so friendly and intelligent. They developed a real friendship, which lasted for the rest of Jimmy’s life. I know this will sound hard to believe, but that hippo knew my father’s voice and would come running on command, no matter where he was in the yard, whether indoors or outdoors.

I was born in 1954, and I saw this many, many times. By the time I started going to the zoo, my father and Jimmy were into their third decade of friendship. No matter how many visitors were crowding around the enclosure yelling “Jimmy!” when my father called him, Jimmy would run or swim over, and he’d stick his head up as high as he could — often resting it on the rails, where he’d snort and stare dreamily at my father. It was like a dog wanting his ears scratched. Visitors and keepers who saw this thought it was remarkable. One keeper told my father that he couldn’t get Jimmy’s attention like that. Jimmy was eventually mated with “Submarie,” and they had babies.

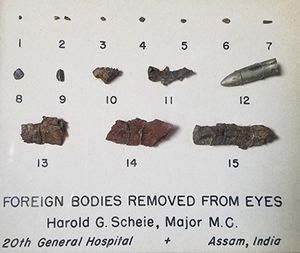

Ultimately, my dad was honored to be the first resident of Francis Heed Adler, a pioneering giant in ophthalmology. He was still with Dr. Adler when World War II intervened. Dr. Isidore S. Ravdin asked him to head the ophthalmology unit with the 20th General Hospital in Burma. It was during this period that he developed the ability to perform eye surgery on a grand scale. He learned how to operate on dozens of eyes in one setting. One of my prized possessions from the World War II period is this:

Photo of foreign bodies removed from eyes.

His most distinguished patient was Supreme Allied Commander Lord Louis Mountbatten, who suffered a serious eye injury in the field which — had the rules been followed — would have prevented him from taking charge of a major battle against the Japanese. He told my father, a lowly captain at the time, that he was willing to risk the eye. They came up with a risky plan of treatment whereby Mountbatten would change his own dressings and put in his own drops according to my father’s instructions. Fortunately, the plan worked, and Mountbatten was able to take command at a crucial point on the ground to defeat the Japanese at Imphal, India. For that victory Mountbatten credited my father, who was awarded the Order of the British Empire, and the two became lifelong friends.

They visited each other a number of times. I will never forget the occasion that Mountbatten went on a tour of our house and stopped dead in his tracks when he spotted my pet alligator George, so big that he lived in a bathtub. Walking over to the bathtub, Mountbatten exclaimed, “I used to have a croc!” picked George up and held him proudly.

Among my father’s other wartime acquaintances were British playwright Noel Coward, Sir Stewart Duke-Elder, the Soong Sisters, Gen. Frank Merrill (of “Merrill’s Marauders” fame) and Gen. Joseph (Vinegar Joe”) Stillwell. One fascinating wartime patient — never famous, but quite distinguished in his own community — was Rang Lang, chief of the local Naga headhunter tribe. It was learned that he was blind, and the Americans hoped that it might be possible to gain the loyalty of this fiercely independent tribe if they could help the chief (who, as it turned out, had simple cataracts).

Dr. Harold Scheie meets England’s Queen Mother.

The chief was led in by bodyguards with long swords who watched constantly, and while my father was a bit intimidated, he managed to remove the cataracts and fit the chief with glasses. The chief was so thrilled upon being able to see for the first time in years that he literally howled when he saw military vehicles driving about. In gratitude, my dad was presented with several chickens and a pair of lovely Naga brides.

Among the thousands of Chinese soldiers my father treated, a lowly private named Wang stayed in the eye unit after his recovery, ultimately becoming an indispensable part of my father’s work with the Chinese. He helped my father learn Chinese, and the two of them were able to cope with many more Chinese patients than had previously been imagined possible. Unfortunately, Wang ended up being accused of malingering thanks to jealous gossip. As the Chinese Army had zero tolerance for malingering, Wang’s superior officers ordered him to be summarily taken out and shot. Armed guards entered the hospital with a death warrant for Wang, and my dad had to immediately spring into action. In a tense scene, he pulled his pistol on the Chinese guards, ordered them out and then he ran to his commander, Gen. Ravdin. Although he was in the middle of a haircut, Gen. Ravdin took the matter up the chain of command to Gen. Stillwell, who then contacted his peer, Gen. Lin Chien Wu. Gen. Wu then sent a reprieve down the chain of command to Wang’s officers and saved the poor man’s life, thus assuring that the eye unit remained in good order for Chinese soldiers.

During the war, my father also earned a doctorate in science for original research into tropical eye diseases. When he left Philadelphia, he was an up-and-coming ophthalmologist, but he returned as a more experienced eye surgeon than ever.

In the post-war period, my dad married my mom and I was born a few years later. When I was only 7, he became the chair of the department at the medical school of the University of Pennsylvania. It’s hard for a little kid to fully understand the pressures that go with being at the top of a field, to say nothing of huge surgical caseloads. My dad could be very difficult at times, and just as he was known for being hard on his residents, he was sometimes very hard on me. But I admired my father’s coolness under pressure, and I loved him for giving me the space to be myself. He allowed me to fill the basement with reptiles, to study taxidermy and even to keep birds of prey.

Dr. Harold Scheie substituted diaper pins for the traditional bamboo plug earrings, much to his patient Chief Rang Lang’s delight.

There was a limit to his patience, though. At the ungodly hour of 4:30 a.m. one morning, my dad was in the bathroom shaving, when a snake that had gotten loose managed to wrap around his foot. I was awakened rather rudely and given one of his legendary ultimatums: “If I see one more snake loose in this house, they all go!” Fortunately for me, we lived in a big house, and snakes are experts at hiding, which meant there was little likelihood of such a freak occurrence happening again.

Snakes aside, that beautiful house (built in the 1920s by the du Pont family for their daughter, who sold it quite cheaply in the late 1950s when mansions had become impractical) was an important part of my dad’s personal life. It was perfect for entertaining, and my dad threw legendary annual parties for the department. Residents, staff, former residents, colleagues, military friends, ophthalmologists and other physicians from all over the country and all over the world would come. They would roast entire pigs; an entire ox and beer and liquor would flow. When my dad worked, he really worked, and when he played he really played, and he encouraged his friends and colleagues to do the same.

My father’s fees were quite low for his time, and he often remarked that when his recent residents set up new practices they would charge more than he did. In that respect he was quite old-fashioned. People too poor to pay, police, teachers, other doctors and fire personnel were in the categories of patients he didn’t charge. He also deliberately didn’t charge rich people. When they would ask about the bill, he would (very diplomatically) let them know that they could always donate to the eye department instead. His patients were very grateful, and their donations ultimately became very important. One such patient was Sen. Joseph R. Grundy; whose generous donation rebuilt the eye department facilities in the early 1960s and continued to generate funding over the years.

Donations from the Pew family (Sun Oil) were largely responsible for the creation of the Scheie Eye Institute, which opened in 1972.

Dr. Harold Scheie with his wife Mary Ann and Lord Louis Mountbatten at the dedication ceremony of the Scheie Eye Institute at the University of Pennsylvania.

My dad took considerable flak for allowing the building to be named for himself, but I remember the period well, as I used to accompany my father when he would visit the Pew family. His name only went on it because of the insistence of the Pews. My dad took care of celebrities such as Ray Charles (whose daughter my father operated on for glaucoma), professional wrestler Gorilla Monsoon, professional boxer Ernie Terrell, the Philadelphia Phillies and Philadelphia’s legendary tough guy mayor, Frank Rizzo.

My father often remarked that as an ophthalmologist, he often felt he had to function as a de facto psychiatrist. People are understandably fearful to the point of neurosis when it comes to their eyes, a fear my dad identified with from boyhood. He often said that nothing could horrify him more than being blind, and it was a major driving force in his life. I cannot forget the way he would agonize over a bad result (even if it wasn’t his fault) and ruminate over what might have been done differently.

He was a tough guy, but I used to feel very sorry to see him worry over his patients. There was nothing he dreaded more than delivering bad news about an eye. I used to accompany him on his rounds at the local Veterans Administration eye unit (to which he donated a great deal of his time and energy without compensation). On one such visit, he was carefully examining the eyes of a polite and eager young soldier who was facing a lifetime of blindness from a Vietnam War injury. My father had to break it to him as gently as he could, that while everything possible was being done, he would probably never see again. The kid kept his composure with such dignity, and I could tell my dad was fighting off tears. He would do anything he could for a patient in trouble.

Another incident I will never forget as long as I live occurred back in the 1970s, when I went into the office to visit my dad at work. He had a difficult case he thought I might be interested in and so he brought me along when he saw the patient. The guy, who was about my age, had what looked like the worst case of pink eye I had ever seen, with eyes almost clouded over. My father introduced me and was joking about how the guy probably got the pink eye from being a little too intimate with his girlfriend, and there was some manly laughter (doubtless sexist by today’s standards). But then my dad suddenly became very serious and turned to the kid’s parents, saying, “Normally there hasn’t been much we can do for venereal herpes [Type II] of the eye. Now, there is an experimental treatment which is not approved by the [Food and Drug Administration], so we can’t legally give it to him. However, if a medicine bottle appears on his nightstand, give it to him as directed, and it may save his eyesight.” He then looked the father in the eye and in the gravest tone, said, “And if it doesn’t work, your son will be in damn serious trouble.” Illegal or not, it worked. The kid’s eyes cleared up. My father was not about to let rules stand in the way of saving someone’s eyesight.

Another example involved a little girl who was dying of cancer. Asked by several people what they could get for her, she said she had always wanted a baby lamb. One of my dad’s colleagues was a researcher who just happened to have some baby lambs in her laboratory, and she decided on her own, “The hell with the rules” and sneaked the lamb into the little girl’s bed early one morning. As luck would have it, my father (who had known nothing about this) happened by and demanded to know what was going on. The researcher knew she had broken innumerable hospital protocols and at that point was sure she was going to lose her job. She told my father the story, and he simply looked at her, looked at the little girl, and said, “Good!”

Harold G. Scheie, MD

My father’s pioneering techniques in glaucoma and cataract surgery are matters of public record, as were his fundraising accomplishments and countless awards. I think he earned his place in the history of ophthalmology, and I hope my personal recollections have helped shine some light on his human side.