There is a growing interest in our society for diversity, inclusivity, and justice. What has not been widely appreciated until recently is that there are significant public health care consequences to racial disparity in delivery of care.

On Sept. 16, 2020, a ophthalmology grand rounds session at UCLA was devoted to this subject. Under the guidance of Lynn K. Gordon, MD, PhD, professor of ophthalmology and senior associate dean of equity and diversity inclusion at UCLA’s David Geffen School of Medicine, residents gave excellent presentations, resulting in a very informative and stimulating session. Their presentations serve as the majority of the basis for this article.

It is interesting to note that concerns about racial disparity in health care were known to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. who stated, “Of all the forms of inequality, injustice in health care is the most shocking and inhuman.”

The “graying” of our society also has large implications on the incidence of vison loss and blindness. By the year 2030 the population over age 65 will be approximately 70 million, twice what it was in 2000, and they will outnumber teenagers roughly 2-1.

Another consideration can be noted in figure 1, where by 2025 the number of Americans between the age of 55 and 80 will reach nearly 90 million, up from just under 60 million in 2006, significantly impacting the incidences of cataract, macular degeneration and glaucoma.

In the case of the latter group, access to care becomes of monumental significance regarding blindness and public health. With societal graying and a declining workforce in ophthalmology, the availability of care suffers disproportionally in underserved populations and regions.

Figure 1. Demographic changes in U.S. population between 2006 and 2025 reflect an aging of society.

Without doubt, vision loss is a major public health issue. In 2004, an estimated 3.3 million people in the U.S. were visually impaired or blind, with that number now 50% larger due to societal aging. Poor vision reduces productivity, increases need for support systems, and induces greater risks for falls, injuries and premature death. Moreover, vision loss is not uniform across adult populations and demographics, being higher in women, the aged, and those of lower socioeconomic status with racial inequity.

As early as 1985 the landmark report, “Report of the Secretary’s Task Force on Black and Minority Health,” issued by then U.S. Health and Human Services Secretary Margaret Heckler, concluded that health disparities accounted for 60,000 excess deaths each year and that six causes of death accounted for more than 80% of mortality among Blacks and other minority populations. It further outlined several recommendations to reduce health disparities and revealed the need to improve data collection among Hispanic, Asian American, and American Indian/Alaska Native populations where national health data were limited or lacking. Additionally, the Black population was reported to have a higher mortality rate than other ethnicities for eight of the 10 top causes of death. Subsequently, a 2002 analysis estimated that the mortality gap between Blacks and whites accounted for nearly 85,000 excess deaths among Blacks that resulted in greater than $80 billion annually lost to health care expenditures and loss of productivity.

Let’s consider the underlying reasons for racial health disparity:

- Genetics

- Socioeconomic

- Environmental

- Structural racism

Structural racism is the “totality of ways in which societies foster (racial) discrimination, via mutually reinforcing (inequitable) systems (housing, education, employment, earnings, benefits, credit, media, health care, criminal justice, etc.) that in turn reinforce discriminatory beliefs, values and distribution of resources,” reflected in history, culture and interconnected institutions.

Institutional racism refers specifically to racially adverse “discriminatory policies and practices carried out (within and between individual) state or nonstate institutions” on the basis of racialized group membership.

Racism has a direct impact on residential segregation, occupational and educational opportunities, and health care access, utilization and quality of care at the neighborhood level. A historic example can be found in Manhattan Beach, Calif., in an area referred to as Bruce’s Beach. According to a Los Angeles Times story from Aug 2, 2020, in the early years of the 20th century, the Bruce family, who were Black, purchased a parcel of property in Manhattan Beach and developed a rather successful resort complex that was highly supported by the Black community.

However, white neighbors, fearing a reduction in property values, along with the KKK and city officials terrorized the owners and forced the resort to close. The property remained vacant for three decades. (For those familiar with the history of South Africa, this is quite similar to the District 6 legacy under apartheid in Cape Town.) This had a very deleterious effect on the family and the Black community in general. However, it is but a microcosm of how marginalized racial groups are forced into socioeconomically disadvantaged communities with hazardous environments that in turn lead to:

- Higher infant mortality rates

- Increased exposure to environmental pollutants

- Increased crime, homicides and incarceration

- Increased risk of chronic diseases and decreased longevity

As a result, these communities have fewer financial resources for health care infrastructure which can lead to:

- Lower quality and smaller number of health care facilities

- Difficulty in recruiting qualified and expert providers

- Poor access to care

- Underutilization of health care facilities and providers

A contemporary example may be seen with regard to the COVID-19 pandemic and the fact that hospitalization and death rates are markedly higher in communities of color, whereas vaccination rates are substantially lower.

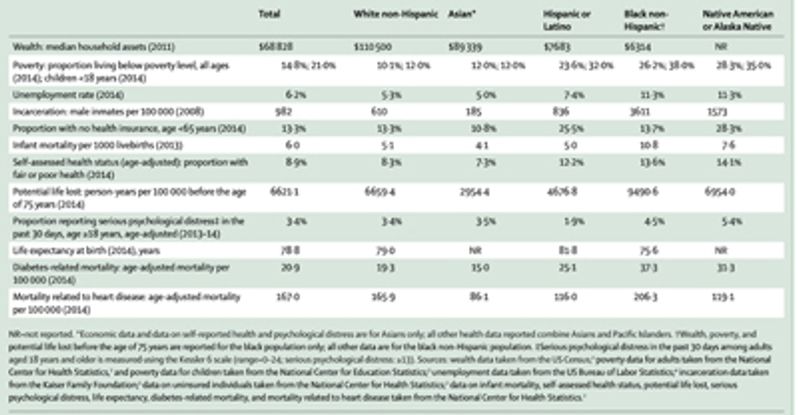

The following table further illustrates socioeconomic impacts on health, life quality and longevity:

Table 1. Socioeconomic and associated health related data by race. (From: Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agénor M, Graves J, Linos N, Bassett MT. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. Lancet. 2017 Apr 8;389(10077):1453-1463.

It is obvious that for the majority of health-related concerns reported in Table 1, the Black non-Hispanic community suffers the greatest inequities, particularly when compared with Asian and White non-Hispanic groups. It is interesting to speculate on the significantly higher number of medically uninsured in the Hispanic population, but that could be reflective of a higher proportion of undocumented aliens for that ethnicity.

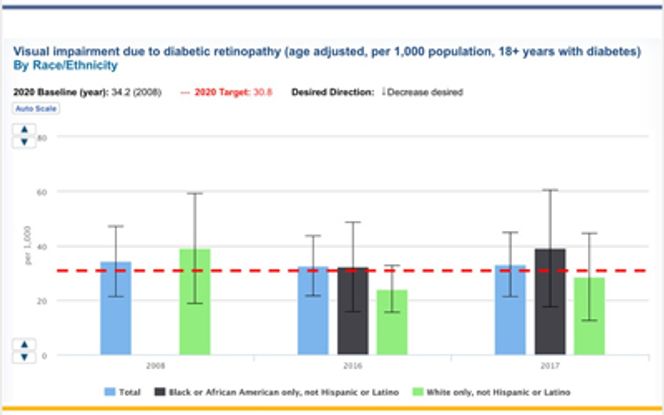

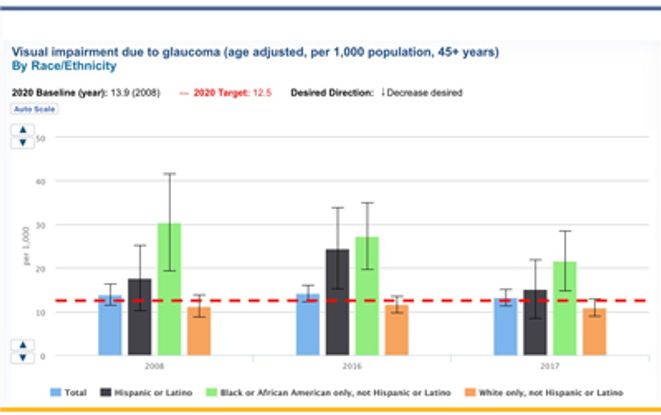

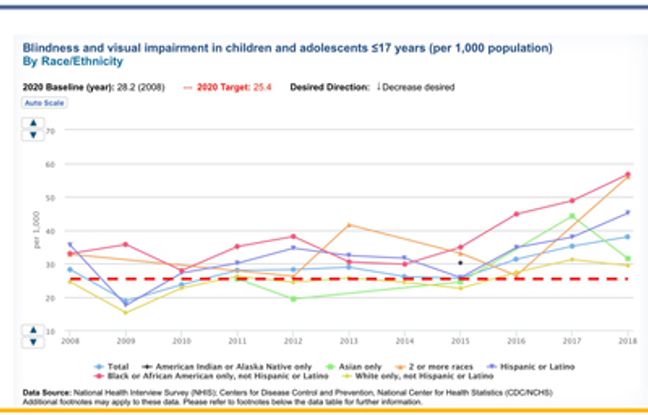

How do these factors relate to health care and specifically eyecare? We note in Table 1 that Black non-Hispanics have twice the diabetes related mortality than do white non-Hispanics. Blacks, therefore, need specifically careful management with respect to diabetes and diabetic retinopathy. Figure 2 reveals a changing demographic with respect to visual impairment from diabetic retinopathy, with Blacks demonstrating a higher incidence of related vision loss in the period from 2016 to 2017, whereas white non-Hispanics experienced a decline between 2008 and 2017. Similarly, with regard to vision impairment from glaucoma, as we can note in Figure 3, Black non-Hispanics have the greatest incidence of vision impairment. As a surrogate for general access to eye care, Figure 4 reveals that Blacks have the highest per capita overall rate of blindness and visual impairment of all racial groups in children and adolescents.

Figure 2. Visual impairment due to diabetic retinopathy in various ethnicities. Note the disparity between the Black and White communities for 2017. Data source: U.S. Census Bureau National Health Interview Survey; the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics (CDC/NCHS).

Figure 3 – Visual impairment due to glaucoma. One can note the greater incidence of glaucoma induced vision loss in the Black population across all time gates. Data source: US Census Bureau National Health Interview Survey; the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics (CDC/NCHS).

Figure 4 – Visual impairment and blindness in children and adolescents less than 17 years of age across various ethnicities, revealing the highest proportion among Blacks. Data source: US Census Bureau National Health Interview Survey; the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics (CDC/NCHS).

While racial predilection to eye disease may impact prevalence, with glaucoma as an example, access to care is an issue of major concern with regard to populations of color. Among the issues are fewer care givers in neighborhoods with lower economic opportunity, and a disproportionately low number of Black physicians, ophthalmologists in particular. There is public health evidence that access to care improves when the physician community reflects the local population at large.

Let’s consider the following: According to the 2014 U.S. census estimates, underrepresented minorities (URM) (Black, Hispanic, Native American, Native Alaskan, and Pacific Islander) account for 30.7% of the US population yet only 6% of practicing ophthalmologists, 7.7% of residents, and 5.7% of faculty fall into those demographics. This is a matter of great significance as there is an unfortunate but genuine historic mistrust of health-related government programs in the Black community.

This can be well understood when considering the egregious Tuskegee Syphilis Study of 400 black men that was initiated in 1932 and did not end until it was “uncovered” by the press in 1972. In that investigation by the U.S. Public Health Service, black men with latent syphilis were recruited and told that they would receive free healthcare and treatment from the government. In reality, and without their consent, many of the men were not treated so that the natural history of the disease could be studied. About a third of the men died of the disease or related causes and some transmitted it to their spouses and in turn to their offspring.

Once discovered, this markedly unethical behavior by the government was the nidus for significant reform and on May 16, 1997, President Clinton formally apologized on behalf of the United States to victims of the study, calling it shameful and racist. "What was done cannot be undone, but we can end the silence," he said. "We can stop turning our heads away. We can look at you in the eye, and finally say, on behalf of the American people, what the United States government did was shameful, and I am sorry." The Tuskegee incident continues to play a role in access to and acceptance of health care in the Black Community, as there is reluctance, particularly among young Black men, to accept vaccination against COVID-19.

This example easily explains a sense of distrust toward public health care initiatives in communities of color and makes the case for the need to level the playing field with regard to the number of URM physicians. Moreover, in non-English speaking communities, language barriers may also sow the seeds of distrust.

How can we improve these inequities? With respect to the future of eye care, one path is to encourage, expand, nurture, and engage URM students to consider ophthalmology as a career choice. The AAO, in partnership with the AUPO has developed the Minority Ophthalmology Mentoring (MOM) program in attempt to increase diversity in ophthalmology by helping qualified medical URM students become competitive residency applicants. Mentors are matched one-one with students to help guide them forward, promote their involvement in research, publications, etc. Moreover, some academic departments identify potential medical student candidates and encourage them. The AAO supplies learning materials and medical students have the opportunity to participate in an 8 month on-line prep course for Step 1 of the USMLE (medical licensing exam). While this program concentrates on just a few students at a time and will take years to bear fruit, it is a positive move.

Another such initiative is the Rabb-Venable Excellence in Research Program (RV) in conjunction with the National Medical Association. The goal of the program is to increase the number of URM physicians in ophthalmology and academic medicine. The program is a pipeline process to expose medical students and residents/fellows to role models, to the skills needed in medical practice and teaching, and to research opportunities while providing mentors.

Approximately 6% of the practicing ophthalmologists in the U.S. are made up of under-represented minorities that constitute 31% of the U.S. population. Increasing the number of minority practitioners would improve access to eye care in underserved communities as these physicians are more likely to practice in these communities than are majority physicians. Recruiting more under-represented minority medical students to the field of ophthalmology and supporting these already in residency programs will help start to decrease healthcare disparities and inequities in the U.S.

Author’s note: With gratitude I acknowledge image contributions from:

Anh Pham, MD, PGY-4, Stein Eye Institute, UCLA

Andrea Yonge, MD, PGY-4, Stein Eye Institute, UCLA

Andres Parra, MD, PGY-3, Stein Eye Institute, UCLA

Lynn K Gordon, MD, PhD, professor of ophthalmology and senior associate dean, Equity and Diversity Inclusion, David Geffen School of Medicine, UCLA

Stacy L. Pineles, MD, MS, associate professor of ophthalmology and residency program director, Stein Eye Institute, David Geffen School of Medicine, UCLA