In 1933 and 1934, the Journal of the American Medical Association reported six cases that highlighted untoward effects of Lash Lure, an eyelash and eyebrow dye popular in the early 1930s. Blindness was one untoward effect, and one particular case of blindness drew sufficient attention to play a major role in improving the safety of cosmetics.

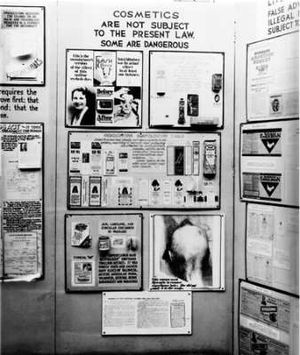

Lash Lure - 1933 FDA Exhibit at Chicago World's Fair

In the 1920s and 30s, American women flaunted makeup as never before. School administrators were scandalized by female students and teachers who appeared in class with eyelashes and eyebrows tinted inky black (and hair bobbed, and knees exposed). Preachers warned from their pulpits that “powder and paint” were condemning a generation of women to eternal damnation — and the preachers were correct in an unintended way because, at that time, nothing prohibited unscrupulous manufacturers from concocting harmful cosmetics that provided profit. Lash Lure was among them.

Lash Lure, the “new and improved eyebrow and lash dye,” was first manufactured in 1933 under a copyright by the Cosmetic Manufacturing Co. of Los Angeles. It was available only in beauty salons. Magazine advertisements said the “new and improved mascara will give you a radiating personality, with a before and after.”

The first adverse “after,” reported in JAMA in July 1933, was severe dermatitis of the eyelids and surrounding skin and exuberant conjunctival edema that began almost immediately after dying the eyelashes with Lash Lure. Complete relief only occurred after removal of all eyelashes. Four months later, JAMA reported four additional cases of adverse side effects with Lash Lure that included a vesicular eruption and marked edema of adjacent skin, as well as keratitis and corneal ulceration and necrosis.

The following year, JAMA reported a fatality associated with Lash Lure. A healthy 52-year-old woman had her right eyebrow completely removed by plucking and Lash Lure applied to the brow and eyelashes. Within a few hours, the right eyelids were swollen closed and, by the next day, the woman had a fever up to 104 F. On the eighth day, she appeared very ill, with deep ulcerations of the right eyelids and palpebral conjunctiva. She died later that day. Plucking the eyebrow had presumably provided multiple entry sites for Lash Lure; death was assumed to ensue from a secondary bacterial infection.

Lash Lure Packaging

Not only was there a rash (literally and figuratively) of reported adverse events from Lash Lure in 1933, but Franklin Roosevelt became president. Roosevelt had a major goal tp better public health. Thus, he provided a receptive ear to petitions for needed changes to the Food and Drug Act.

A 1906 statute had added regulatory functions to the FDA’s original mission of research, but only for food and drugs and to a disturbingly limited extent. When Roosevelt took office, muckraking journalists, activist women’s groups and consumer protection organizations, including Consumers’ Research, pushed a reluctant Congress to further revise the FDA, including regulation of cosmetics.

In addition, the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the FDA waged extensive publicity campaigns to promote revision of the Act, including a display at the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair to highlight the lack of regulation of cosmetics. These prominently featured “before” and “after” photos of a woman blinded by Lash Lure. A reporter dubbed the exhibit “The American Chamber of Horrors.”

Time magazine reported, “In the Department of Agriculture’s ‘chamber of horrors’ last month Mrs. Franklin D. Roosevelt discovered two photographs, pressed them to her breast crying, ‘I cannot bear to look at them.’ The photographs were of a woman who had got some ‘Lash-Lure’ eyebrow and eyelash dye in her eyes.” Paramount released a newsreel about changes proposed for the 1906 Act, which included footage about several women who had corneal damage due to use of an “eyelash beautifier.”

Despite these many efforts, it was not until 1938 that the federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act passed, which finally regulated cosmetics. The first product seized under the new law was Lash Lure, which was alleged to be adulterated with “a poisonous or deleterious substance, a coal tar preparation, paraphenylenediamine.” U.S. cosmetic manufacturers were notified that use of PPD in cosmetics would be prosecuted. The company manufacturing Lash Lure had sought to protect itself against damage suits by enclosing in each package a release to be signed by customers absolving the beauty shop, distributor and manufacturer from any blame if the use of Lash Lure resulted in injury.

Paraphenylenediamine is a white powder derived from aniline, which is a component of coal tar, that acquires color upon exposure to air. In about 1.5 percent of individuals, PPD causes an allergic reaction, ranging from mild dermatitis to an urticarial reaction to, rarely, anaphylaxis. Contact dermatitis is particularly severe around the eyes because periocular skin has the thinnest stratum corneum of all skin in the body.

The prevalence of contact sensitization to PPD is increasing in North America. In 2006, the American Contact Dermatitis Society voted it Allergen of the Year.

The 1938 Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act did not require FDA approval before a cosmetic is marketed. However, it held manufacturers of cosmetics legally responsible for the safety of their products, set standards for ingredients of cosmetics and mandated a list of “harmless and suitable” coal-tar-derived colors that could be used in cosmetics. Interestingly, hair-coloring agents were exempt. Thus, PPD use in cosmetics applied to the skin was prohibited, but use in hair dye was permitted. In1960, amendments strengthened the safety requirements for all color additives, except for those in hair-coloring agents.

Today, PPD is a widely-used component of hair dyes because it provides a natural look and permanency, and the color doesn’t fade or change with shampooing or perming. The number of American women coloring their hair increased from 7 percent in the 1950s to at least 75 percent in 2011. Now there are effective treatments for allergic reactions, which were not available in the 1930s. Nevertheless, there are recent reports of deaths due to severe allergic reactions to PPD-containing hair dyes.

Of note, there can be cross-sensitization between PPD-containing hair dye and other PPD-containing substances, such as some henna tattoos. Moreover, there can be cross-sensitization between PPD and other compounds with an amino group in the para position of their benzene ring, including sulfonamides (antibiotics), sulphonylureas (antidiabetic agents), local ester anesthetics (e.g., benzocaine, tetracaine), para-toluenediamine sulphate (a replacement for PPD in some hair dyes), and sunscreens with para-aminobenzoic acid.

Not only are hair coloring agents still a heath threat today, but cosmetics also continue to pose a risk. For example, FDA and European Union rules permit a small amount of mercury (< 65ppm) to be used as a preservative in eye cosmetics — not so in Canada and Japan.

In many parts of the world outside the United States, PPD is present in eyelash dyes. An example is Combinal, a top-selling eyelash dye, made in Austria, which is 2.38 percent PPD. Its label has warnings, including “can cause an allergic reaction…contains paraphenylenediamine…for professional use” and “use suitable gloves.” However, Combinal is available on Amazon for $19.99 with no warnings included. Thus, although designed for salon use, Internet sales of such products are available to anyone, and allergy cases involving PPD may increase as Internet sales expand.

In 2013, it was estimated that the average American women spends $15,000 on beauty products over her lifetime, nearly $2,750 on eye shadow and $3,770 on mascara. Those figures are expected to progressively increase. The global beauty industry is growing at 7 percent a year, more than twice the rate of the developed world’s GDP. In 2014, profits of cosmetic manufacturers globally were about $255 billion and were expected to reach $316 billion dollars by 2019.

Investing in a cosmetic company could be the key to becoming a billionaire. However, if investing in cosmetics for your own use, beware of dying to be beautiful.