The journalist, Tom Brokaw dubbed the generation that grew up in the Great Depression and then went on to fight in World War II the “Greatest Generation.” The ophthalmologist and eye pathologist Leonard Christensen is a splendid example of that generation.

He was born August 16, 1913, in Cloquet, Minnesota, the youngest of three children of working-class Norwegian immigrant parents. He graduated from the University of Oregon Medical School in 1941 and after a one-year internship at Ancker Hospital in St. Paul, MN, he served in the South Pacific as a Navy flight surgeon until the end of World War II.

He completed his ophthalmology training at the University of Oregon Medical School and received a Heed Fellowship for a one-year study of Ocular Pathology with Georgiana Dvorak-Theobald, MD, in Chicago and Algernon Reese, MD, in New York. He returned to Oregon and joined the faculty at the University of Oregon Medical School where he worked until his retirement in 1978. From 1978 until 1989 he was in private practice in Portland, OR.

Dr. Christensen began his career in clinical ophthalmology before the days of widespread sub-specialization, when the specialist took on the entire repertoire of surgical eye procedures. Thus, he was one of the last of the high-volume surgical ophthalmologists who “did everything.” Well, not quite everything. Since he often declared that his expertise in pediatric ophthalmology only included patients over age 65, he referred pediatric motility patients to his associate and department chairman, Kenneth Swan MD. Being based at the university, he was restricted to seeing only patients referred to his care by other physicians.

Nevertheless, Dr. Christensen had an extremely full practice that included retinal, corneal and cataract surgery as well as all aspects of glaucoma. At the same time, he was the working ocular pathologist, as well as director of the Eye Pathology Laboratory. He was one of a generation of eye pathologists who were essentially the founders of this subspecialty in the United States. It was a time when training in the discipline was difficult to come by and took initiative and sacrifice to obtain. He was an early member of the Eye Pathology Club, which evolved into The Verhoeff-Zimmerman Society.

Graduation portrait of Leonard Christensen, MD, MS from the University of Oregon Medical School, class of 1941. He served as a resident and faculty memer from 1951-1978 and helped create the pathology lab and eye bank for Casey Eye Institute in Portland, OR.

He was a busy man who always had time to get something else done. He established the first eye bank in Oregon, served on and was chair of the American Board of Ophthalmology, and published dozens of research articles, book chapters and symposia.

He was a shy, almost reclusive man and yet was very approachable. He had a relaxed and easy demeanor that brought him an abundance of friends and acquaintances. To them he was just plain “Chris,” to many in his family he was “Len” and for me he was “Uncle Len.” He was introspective and deeply analytical in his thinking and had great confidence in the ability to solve difficult clinical problems through a combination of basic science and common sense.

This approach to solving problems is well demonstrated when one reviews his list of publications. He had several “firsts” to his credit: first histologic demonstration of cytomegalovirus in a human eye; first person in Oregon to perform a penetrating keratoplasty; first report of a drug that when given systemically reduced elevated intraocular pressure without exerting a mechanical effect on the eye. This drug, Dibenamine, was first reported in the pharmacology literature in 1947 and considered the prototype of a particular class of adrenergic blocking agents.

In 1949, Drs. Christensen and Swan completed and published a study of this drug’s effect in lowering intraocular pressure when given systemically. These findings prompted other investigators and eventually led to the discovery and use of carbonic anhydrase inhibitors, which are widely used in glaucoma treatment today. Dr. Christensen submitted this work as a thesis and was awarded a Master of Science degree in pharmacology.

He was one of the first surgeons to show that eccentric corneal lesions not amenable to trephine isolation could be excised and the defect successfully repaired by freehand keratoplasty. The procedure is useful in corneal melting disorders, deep corneal ulcers and is especially helpful with acid and alkali burns that affect the limbus. With chemical burns, it is necessary to remove all damaged tissue while planning a lamellar graft repair. Many chemical burns will involve the limbus and adjacent sclera. In such cases those areas need to be removed as well. In his American Ophthalmological Society thesis, “The Nature of the Cytoid Body,” he presented a significant advancement in understanding the pathological changes involved by carrying out an elegant histochemical study of the subject.

Ironically the earliest of his scientific firsts nearly became his last. It occurred on one of the Admiralty Islands in the South Pacific Ocean where he was stationed with his Navy medical unit during World War II. There was a problem of severe and sometimes fatal intestinal illness, which was narrowed to a drinking water source. But which one? The only option to find out was to test the water sources on the personnel themselves. Dr. Christensen volunteered, and the problem was eventually solved but he was hospitalized for months, severely emaciated and dehydrated.

During his hospitalization, Dr. Christensen received a visit from Robert Hill, MD, who was passing through the island. Dr. Hill, who had been a college and medical school classmate of Dr. Christensen, did not recognize him initially and was shocked to learn that his former colleague’s weight had dropped to less than 100 pounds. On leave to the United States, subsequently, Dr. Hill stopped in Corvallis, OR, to visit with Dr. Christensen’s brother Bert. Dr. Hill informed Bert that that he didn’t think Chris would survive.

Multonomah County Hospital house staff, 1946-1947. Dr. Christensen is fifth from the left in the top row.

Dr. Christensen was also an iconoclast and frequently skeptical of the ophthalmic dogma of his day. He demonstrated that narrow angle glaucoma and flat anterior chambers required a component of positive posterior vitreous pressure and was not caused simply by an enlarged lens and/or wound leak, the prevailing wisdom at the time.

During his early career, it was not uncommon for some practitioners, including a few ophthalmologists, to prescribe long acting topical anesthetic ointments for corneal abrasions and other surface problems. Topical anesthetics are not appropriate for chronic use for several reasons including corneal drying, loss of the blink stimulus and its action to stop mitosis of the corneal epithelium. He reported these severe complications and even advocated abolishing their production.

A rare but devastating complication from cataract surgery is epithelial ingrowth, usually through a corneal-scleral surgical wound. One study showed about 1% incidence when no limbus-based conjunctival flap was used. By using a limbal-based conjunctival flap this complication didn’t appear in a series of 3,000 cataract cases studied. He also described numerous surgical innovations, many of which are still in use today.

Even at the end of his professional career, he was looking forward to and excited by new developments and innovations in ophthalmology. His enthusiasm was infectious to those around him. I was privileged to live in his home during my medical school years, a time during which he was widowed with three small children. Our numerous talks developed my own interest in ophthalmology. Most ophthalmology topics usually centered around procedures and recently published scientific data.

When his daughter Laurie was in medical school and it was 20 years later, his focus was on care and empathy, especially for patients who were going blind. He felt that care was more important than diagnosis and treatment in these cases, but diagnosis and treatment were still important and necessary. Also, he reminded her to retain a caring attitude with patients experiencing complications.

He never talked much about the war, but he told Laurie that his near fatal illness made him realize how frightening these situations can be and why kindness, care and empathy are so important. He was the perfect role model of the dignified, compassionate physician with excellent clinical skills and a strong science background. His keen intellect and dry wit revealed a particularly insightful view of the world. This alone was an invaluable experience, which has served me well. He had an avid interest in current events, especially political and economic issues.

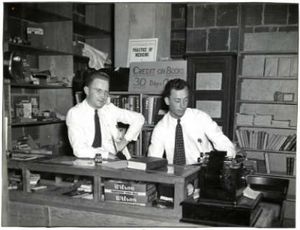

He always looked for investment opportunities, preferring those which he felt would be stable and conservative. His investment habit began in 1938 during medical school. The stable and conservative self-restrictions followed this first endeavor. He and fellow classmate Robert Rinehart decided to open a for-profit bookstore at the medical school (image below) as the students believed that the downtown stores were too expensive. It started in a large closet in the Basic Science building and was only open for limited hours.

Leonard Christensen, MD, (left) and Robert Rinehart, MD, as medical students, working behind the counter in the student bookstore, spring 1941. Note: Wilson tennis ball also for sale.

It wasn’t long before the administration responded to complaints from the downtown booksellers. When the partners were ordered to close the store, they began to operate only in the evenings and required a secret code knocking sequence to gain admittance. However, it wasn’t long before the “secret knock” turned out to be the dean. Chris was there alone but out of panic and fear he picked up a large box of pencils and asked the Dean where they would get the money to pay for all this merchandise. Eventually it was decided they could stay temporarily. When I was a student (‘57-61), the student bookstore was still going strong and was privately owned by a couple of my classmates who were required to sell their interest upon graduation. The store is still in business; I am not sure of the ownership.

You might ask what Dr. Christensen did in his spare time and what were his hobbies? Most Saturday afternoons he played golf. He had a low handicap, and one year he was the champion at his country club. He was also a football fan both as a spectator watching TV football on Sunday, and occasionally playing touch football in the back yard with his boys, the neighborhood kids, and me. Since he and I were the only adults, we were always on opposite sides. My position was usually a roving one but his was quarterback and he passed almost all the time. I will say he had an advanced skill set for backyard touch football, which usually beat my team.

Other interests he enjoyed were reading, moose hunting once a year with his brother Harold, and raising Norwegian Elkhounds. As a result, we all got to enjoy moose meat several times during the following winter as well as having bones for the dogs.

He expanded his non-medical interests in 1961, when he married Kathleen “Kaye” Mahoney, who among other things had a wonderful positive influence as a stepmother for the children. This was important for all the kids but especially daughter Laurie, whose birth mother, Virginia, had died after a long and debilitating illness when Laurie was only 4. In addition to her stepmother duties, Kaye was part of the volunteer administrative staff whenever the American Board of Ophthalmology oral exams were held.

Dr. Christensen encouraged his children to follow their own dreams and they did. His son Mark is a novelist; his other son Scott is a musician and composer; and his daughter, Laurie, chose to be a pediatric ophthalmologist. Had they elected to practice together, the office could have included motility patients under the age of 65.

Leonard Christensen, MD, died peacefully in his home Nov. 2, 1999, from cancer and complications of Parkinson Disease.

Ophthalmic History Editors: Daniel M. Albert, MD, MS and Donald L. Blanchard, MD