Lester T. Jones, MD (1894-1983), was an international authority on the anatomy of the head and neck who became known as one of the best surgical anatomists in ophthalmic plastic surgery. One key to his expansive knowledge: a lifelong fascination with and practice of dissecting orbits, both human and animal.

Born in Danville, Ky., Dr. Jones attended high school and Pacific University in Oregon after the family moved to Forest Grove in 1906. Dr. Jones was the last known survivor of the University of Oregon medical school class of 1921. Medicine was a strong family tradition as his brother, Arthur Jones, MD, and two sons, Warren L. Jones, MD, and Richard T. Jones, MD, all became doctors.

Dr. Lester Jones was an active teacher of medical and dental students, ophthalmology residents and ophthalmologists in practice. He conducted classes both locally and nationally.

To better understand the fine structure of orbital muscles, he often conducted hours and hours of lab dissections with the tissues under water. This demonstrated fine structures that had previously been underappreciated.

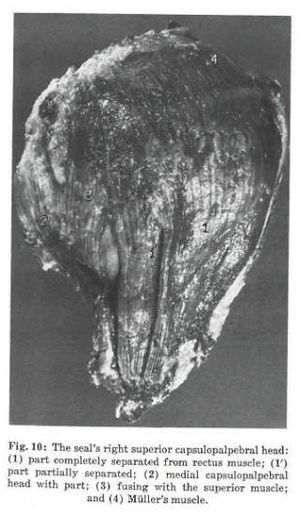

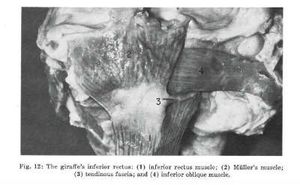

He was widely known for his comparative anatomy studies and his application of this knowledge to his orbital surgery work. Even the orbit anatomy of seals (Figure 1) and giraffes (Figure 2) held valuable lessons in understanding usual human anatomy along with variants.

Figure 1: The seal’s right superior capsulopalpebral head: (1) part completely separated from rectus muscle; (1’) part partially separated; (2) medial capsulopalpebral head with part; (3) fusing with the superior muscle; and (4) Müller’s muscle.

Figure 2: The giraffe’s inferior rectus: (1) inferior rectus muscle; (2) Müller’s muscle; (3) tendinous fascia; and (4) inferior oblique muscle.

Dr. Jones’ son, Richard T. Jones, MD, PhD, was chair of biochemistry and acting president of the University of Oregon Health Sciences Center. Richard Jones recalled that his father “worked in medical school. He was a diener in the anatomy department, and the bodies that were donated were brought to him, and he would embalm them and get them prepared for the anatomy classes.

“For internship he went back to Philadelphia to the Polyclinic in Philadelphia. (Along the way he earned extra money from Portland to Chicago by working as a shepherd. He transported a herd of sheep and would let them out at the various stops to graze in pastures. Rounding them up was then a chore.)”

In the 1920s, the Polyclinic in Philadelphia was a major center for eye, ear, nose and throat, connected with both the University of Pennsylvania and Wills Eye Hospital faculties and had distinguished teachers from both institutions. It had descended from David Hayes Agnew’s school of anatomy, which subject remained one of its strengths. Perhaps his time there added to Dr. Jones’ love of the study of anatomy.

While in Philadelphia, Dr. Jones’ son said his father took an internship and perhaps did some work at New York’s Bellevue Hospital as well. “Then he got a job as a ship’s doctor on a freighter going to South America and went down there. And then, after that stint, he came back to Portland and started in general practice group. But they needed somebody in eye, ear, nose and throat; they didn’t have a specialist.

“So Lester and his wife decided that he ought to go to Vienna to study eye, ear, nose and throat. And so they went to Vienna. They left my older two brothers with my grandparents — my mother’s parents who had come out from Nebraska — to take care of them, for somewhere between six months and a year, that’s how long it took to specialize in those days. And that was in 1928.”

When he got to Vienna, in 1928, Ernst Fuchs (1851-1930) was still actively teaching in Vienna and lecturing in both German and English.

After these studies, Dr. Jones returned to combat in World War II, rising to the rank of captain in the Navy (during World War I, he had served as an orderly in the army). At the end of the war, he was the executive officer of the Bremerton Washington Naval Hospital. After World War II, he returned to Portland to practice ENT and ophthalmology.

Dr. Jones was committed to perpetuating the “whole physician” — a dedicated professional whose primary concern focused on the patient; one who conducted research to create better diagnostics and treatment methods, and then shared the fruits of that research through publications as well as a wide variety of educational forums. Physicians who showed any interest in surgical anatomy knew he would spend as much time as needed to teach them and show them subtle inter-connections and variants of orbital structures.

Dr. Jones was boarded in eye, ear, nose and throat. This allowed him to develop significant research in the lacrimal system. He was the first to recognize how tears pumped through the lacrimal tract. This was followed by tests to diagnose obstructions in the lacrimal system.

The Jones I test consisted of placing dye in the tear film and looking to see if it appeared in the nose at the end of the tear duct. The Jones II test was done following a negative primary dye test. One slowly injected a small syringe with 1 mm of normal saline solution through the lacrimal cannula. No fluid coming out of the nose was evidence of complete obstruction. If dye appeared, the obstruction was in the lacrimal duct.

The development of the conjunctivodacryocystorhinostomy was one of his significant achievements for the tearing patient. This evolved into the development of a tube (Figure 3) that would carry tears to the nose for those who had no canalicular system.

Figure 3: Jones Tube

After many trials, his son Dr. Richard Jones, suggested he work with Gunther Weiss, a scientific glass blower. This resulted in a pyrex tube, since it had capillary attraction. The procedure was a DCR followed by placing the pyrex tube through the caruncle into the nose. At the beginning other colleagues criticized Dr. Lester Jones, but the pyrex tube proved e successful. It is still used around the world.

Dr. Jones also re-introduced the levator aponeurosis repair for acquired myogenic ptosis. This procedure lends itself to local anesthesia and anatomical defects that leave the conjunctival surface intact. It may be combined with blepharoplasty. Post-operative modification is easiest with this ptosis repair.

Dr. Jones traveled worldwide, demonstrating and teaching his procedures. He served on the volunteer faculty of the Oregon Health Sciences University School of Medicine and retired as an emeritus professor at the age of 82. In addition he was president of the staff of Good Samaritan Hospital and Medical Center in Portland, Ore.

Malcolm Marquis, MD, met Dr. Jones during his ophthalmology residency from 1964 to 1966. He remembers that Dr. Jones’ father was a minister, and the whole family (father, brothers, sons) were “remarkable people,” “strong minded, opinionated” and talented. Dr. Jones was “always honest and open” and a “perfectionist.”

He described Dr. Jones as “crusty” but modest and correct. Despite “many traumatic things in his life,” including the death of a son and his first wife, he retained a “good sense of humor” and went on to have a happy second marriage. Punctuality was extremely important to him, as he was always on time himself and expected it from residents and others.

Dr. Jones had an arrangement with the Portland zoo whereby, when an animal died, it was decapitated and Dr. Jones dissected it (presumably concentrating on the orbit) in the basement of his home. Dr. Jones’ knowledge of the anatomy of the orbit was based in large measure on his personal dissections and exceeded what was available in papers or books. “He relished minor points.”

When he operated, the OR always had a number of “visitors and spectators” and these were teaching sessions. He would often pause to allow visitors to take pictures, even though this slowed his surgery. He loved to “pass on knowledge” and cared little about compensation for his books or lectures.

Although highly regarded by his peers, Dr. Jones was most active in local ophthalmology affairs. Even so, he received national recognition by societies and institutions. In 1974, the American Society of Ophthalmic Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery set up The Lester T. Jones Surgical Anatomy Award to be given to an individual who has made an outstanding contribution to ophthalmic plastic and reconstructive surgery. The first award went to Marvin H. Quickert, MD, for his application of anatomy to surgical approaches.

The American Academy of Ophthalmology also chose Dr. Jones to write the Academy’s booklet on the anatomy of the orbit.

Dr. Jones received many other awards and some were also given in his honor. In 1980, the board of trustees of Lewis and Clark College honored Dr. Jones for his research and professional work by presenting him their annual Aubrey R. Watzek award.

Oregon Health Sciences University named the first endowed chair at Casey Eye Institute after Dr. Jones. The Lester T. Jones Chair extends the concerns and interest of this extraordinary man, but saluting his belief in the importance of healing, teaching and discovery. (Figure 4) (Editor’s Note: John Wobig, MD, was the first physician chosen for this position.)

Figure 4: Dr. Jones on the right and Dr. Wobig on the left.

I should point out that Dr. Jones had other interests and skills as well as medicine. While a student at Pacific University, he played guard on the football team. At his home, in Portland he maintained a well-kept landscaped yard, had a beautiful rose garden and it was not unusual to find him picking plums and walnuts at his farm in Wilsonville, Ore. Dr. Jones’ grandson Gary also became a physician.

Among many fond family memories, one stood out: "My grandfather was quite the gardener. He … had great pride in his blueberry bushes. I always remember the blueberry bushes, if for no other reason because, when it was blueberry season, the birds would come down from everywhere. It was like something out of Hitchcock, you know, all the birds coming in. So he had to put these big nets over it. So it was always this fantastic, huge, huge hedge of blueberries, all in netting, and you’d kind of crawl inside there and pick these fantastic, luscious blueberries.”

Down through the history of the ophthalmic community in the Northwest, Dr. Jones’ accomplishments and contributions, as well as his moral character, will be held in high esteem by fellow colleagues, physicians of other countries and all his many students and patients.