My father was born on Nov. 15, 1920, at Columbia Hospital in Washington, D.C., and the city was his home for more than 80 years of his life. His parents were Swiss and German immigrants; they owned a bakery, and my father was raised in a home above the shop.

The discipline and work ethic instilled in him as a child working in the pastry shop greatly influenced his career in ophthalmic pathology. In fact, he liked to say that he chose a career in medicine because he did not want to work as hard as his parents. Fortunately, he could not shake the work ethic, determination, self-discipline and motivation that were integral portions of his personality and influenced every aspect of his life.

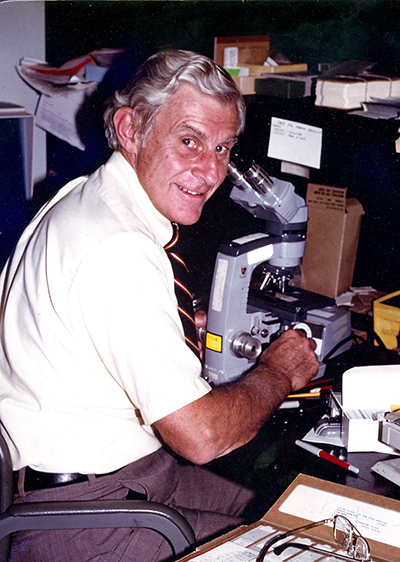

Lorenz E. Zimmerman, MD, at work at the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology.

Sports were always a big part of my father’s life. He played football and baseball in high school and considered playing competitively beyond graduation. At age 40, he was introduced to tennis. He pursued tennis in the same way that he applied himself to every other interest and became a very competitive player. Much of his later social interaction at ophthalmology meetings revolved around early morning tennis matches with colleagues and friends. Many who admired him called him “Zim.”

Physical activity as a part of a healthy lifestyle was routine for my father, even before it was in vogue. He was also a great sports fan, and in high school and college worked as a vendor at the old Griffith Stadium in Washington, D.C., so that he could observe Redskins and Senators games. He was a lifelong Redskins fan and was known to embarrass my mother at social functions by seeking out a television to watch a game. He even got in trouble along with Bob Ellsworth at Bob’s daughter’s wedding because they were caught in the bar watching the Redskins-Giants game.

Fortunately for ophthalmology, my father pursued medicine and graduated from George Washington University (bachelor of science, 1943 and MD, 1945). He entered the U.S. Army Reserves in 1943 during medical school and, because it was wartime, completed medical school in two years. After an internship at Gallinger Memorial Hospital in Washington, D.C., his original interest in the field of internal medicine waned. He stated that he realized that much of internal medicine was an “overlay of psychosomatic medicine and that, if I did not want to see patients whose problems were more in their heads than in their bodies, I ought to stick with genuine pathology.”

After serving as a general medical officer at the Pentagon, he completed his residency in pathology at Walter Reed Hospital in June 1950 and was sent first to Tokyo and then to serve in the Korean War as the pathologist in charge of a mobile medical laboratory.

Lorenz E. Zimmerman, MD, in Korea as a pathologist in a mobile army hospital.

On return to the States in 1952, he was assigned to the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology (AFIP), rotating through various subspecialty departments until he landed permanently in ophthalmic pathology, a department where he had no experience. In the early 1950s, there were few general pathologists interested in ocular pathology. None with experience were available at AFIP.

Many years later, my father wrote, “I thought it was a stroke of real good fortune for me personally, not because I had any preconceived notions or interest in pathology of the eye, but I just knew that it was a gold mine … in the figurative sense ... in terms of having a wealth of material available and having this tremendous inflow of material, not only from military institutions all over the world, but from the civilian sector.” Due to the war, many of the civilian institutions that had been doing subspecialty pathology had shut down due to lack of manpower, but he delighted in his inheritance of an instant backlog of 5,000 cases!

My father was fortunate because tackling a backlog of this magnitude in a field he knew little about could have been a disaster. But Helenor Wilder, the ophthalmic pathology technician who led the department during the war, mentored him, introduced him to the key people in academic ophthalmology and arranged for him to be her successor in one of the elite eye pathology clubs. She facilitated his acceptance into the field of ophthalmic pathology at a time when he had never written a paper on the subject. He also considered himself fortunate to have several military ophthalmologists assigned to the ophthalmic pathology department early in his tenure; these men taught him some clinical ophthalmology, as they were all learning eye pathology.

The backlog of cases meant that, by the time my father rendered a final report, it was often five to six years after the specimen had been submitted. He routinely added a comment at the end of each report stating, “We would appreciate your providing follow-up information.” It was in this manner that he developed a wealth of clinicopathologic information with significant follow-up.

My father’s willingness and enthusiasm to pursue passionately a subspecialty in pathology, about which he had no prior interest or knowledge, set the stage for a series of more than 50 years of professional contributions to ocular pathology and oncology, including the education of ophthalmologists in eye pathology. His position at the AFIP allowed him to educate residents, fellows and practicing ophthalmologists to varying degrees. He was able to do this because of relationships between the American Registry of Pathology, the American Academy of Ophthalmology, funding through the National Institutes of Health and other national eye societies, and the emphasis that the American Board of Ophthalmology placed on candidates learning eye pathology as part of their education.

Lorenz E. Zimmerman, MD, and his wife Anastasia on their wedding day.

His reputation as a teacher was unsurpassed partly due to his qualities of both humility and perfectionism. He demanded even more of himself than he did from his fellows. Dr. Fritz Naumann said of him, “I only recall one situation which would annoy him – if his fellows would not criticize a rehearsal of one of his major lectures. Not criticizing him was interpreted as intellectual laziness and lack of interest in the subject.”

His greatest passion was teaching. Daniel Albert, MD, observed, “Zim had the ability to look at slides from diseases that had been studied for over a century and make new observations and correlations. Examples of this can be seen in his reports on ocular toxoplasmosis, angle recession glaucoma, phacolytic glaucoma, hemolytic glaucoma, retinocytoma, melanocytoma, juvenile xanthogranuloma and many others. His vast knowledge and insight into the pathology of eye diseases, backed by his total mastery of the basics of pathology, made him a uniquely qualified mentor. This knowledge was combined with his gifts as a clear and precise teacher, patience, intellectual honesty, and humility.”

Over the years, his former fellows developed active ophthalmic pathology laboratories at major institutions across the country. My father noted, “My entrance into the field was made comparatively easy by the fact that I hardly had any competitors. There were very, very few people who were well-trained who were in the field of ophthalmic pathology, and really none of them doing ophthalmic pathology on a full-time basis.” But my father had the uncommon trait in great men of caring more about the success of his trainees than in his own accomplishments. Fred Jakobiec, MD, recalled, “While some leaders in their fields are threatened by the most talented young people they have trained, Zim has exhibited the trait of promoting their careers at every turn.”

In his retirement, my father continued to be concerned about the education of ophthalmologists in ophthalmic pathology, especially with the economic realities of healthcare in the 21st century. He was clear about his wish that collaboration between clinicians and pathologists continue in ophthalmology for the benefit of patients.

In his acceptance speech for the 1999 Helen Keller Award, he stated, “Many highly significant advances and the development of new concepts have evolved merely as a consequence of the comingling of clinicians and pathologists in the retrospective clinicopathologic discussions of cases thoroughly studied at academic centers. It doesn’t always require the latest in extremely expensive high-tech equipment and the use of experimental animals to make major advances towards the prevention of blindness.” It was his wish that future clinicians continue to be well educated in ophthalmic pathology by having opportunities to interact with pathologists in efforts to better understand disease processes and improve treatment for our patients.

Although my father’s professional life was busy, he was very much a family man. He met my mother in Korea, where she was serving as an Army nurse. They reconnected seven years later when both were stationed in Washington, D.C. — my father at the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology and my mother at Walter Reed Hospital. They married in 1959 and together raised six children. The last of their six children is my brother Larry, who was born in 1967. Larry’s birth begins an ironic story of intermixing of professional and personal challenges and contributions in the field of retinoblastoma.

My father’s first paper on retinoblastoma was co-authored with Marshall Parks, MD, and was published in 1960. His subsequent landmark work in retinoblastoma became intimately intertwined with his personal life when Dr. Parks diagnosed Larry with bilateral retinoblastoma at 4 months of age. This began a series of ironies and contributions, including several “firsts” in retinoblastoma science, nomenclature and treatment by three generations of the Zimmerman family.

Lorenz E. Zimmerman, MD, with his son Larry at a high school lacrosse game.

Larry was one of the first babies treated with intracarotid chemotherapy and subsequently bilateral external beam radiotherapy — both experimental at the time. Larry’s daughter, Perry, survived trilateral retinoblastoma — a rare condition even among patients with bilateral retinoblastoma. A second irony involving the Zimmerman retinoblastoma story: The term “trilateral retinoblastoma” was coined by my father, based on basic science research conducted in his laboratory in collaboration with Mark Tso and my brother, Brian, who was a student researcher at the time. Another contribution to the science of retinoblastoma prevention occurred with the birth of Larry’s second daughter, Lizzie, who was born via preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) to prevent the transmission of the retinoblastoma gene. Her birth marked the first child born via preimplantation genetic diagnosis, not just for retinoblastoma, but also for any cancer-related genetic disease.

Through this journey of compiling our family’s contributions in the field of retinoblastoma, it has become clear to me that my father’s passion for his work was driven not only by his love of science, medicine and pathology but also by his personal challenges in the field. His life’s work was devoted to a triad of clinicopathologic correlation, teaching, and research with the hope of giving others what his family had enjoyed: the ability to overcome a potentially fatal illness with useful vision to enjoy all that life has to offer.

My father did enjoy life. He cherished family time with my mother, their children and grandchildren and even their great-grandchildren. He taught all of us the value of hard work and discipline — in physical activity, competition, diet (well, except for the volume of ice cream he could consume) and keeping balance in life. He could be a fierce competitor in sports. He played tennis into his 80s and fast-pitch softball into his 60s. My brother Skip recollects, “To me, he is the greatest third baseman I ever saw play fast-pitch softball. People call him the vacuum cleaner — nothing gets by him.”

My father was known to be quirky. Growing up during the Great Depression caused him to adopt a “waste nothing” mentality. He used to entertain the grandchildren and their friends by eating part of the corncob after he had finished the corn! His soup bowl was mostly filled with bones, which he would enjoy chewing down to the marrow … and as much as he loved the meal, he cherished even more the laughs it generated among the kids. This knack for entertaining grandchildren earned him a name change from “Grandpa” to “Cool Papa.”

He had hobbies, and he pursued them passionately. He could be found almost every morning gardening or tending to the fish pond he dug himself. After his death, my daughter Stacey wrote this about him and my mother: “The most remarkable thing about Nana and Grandpa’s hands, though, was what they did for the world. The work of Grandpa’s hands in his breakthrough research in pathology is the most obvious, and that humble handshake we see in the old photographs of him accepting prestigious awards is a testament to his self-effacing character. Cool Papa took this beyond his career, however, creating beauty for everyone’s enjoyment in his garden and backyard pond.”

The Zimmerman family at a 1996 reunion.

For my father’s work in ophthalmic pathology, he received the highest honors in our field: Jackson Lecture (at age 40), Ernst Jung Prize in Medicine, Donders Medal, Jules Stein Award, one of the 10 Most Influential Ophthalmologists of the 20th Century (ASCRS), Helen Keller Prize for Vision Research (ARVO), Howe Medal (AOS) and the Academy’s Laureate Award. Although he was appreciative of all the recognition he received, it is possible that his greatest legacy is not in the science or medical advancements but in the lessons in humility, professionalism and ethical conduct he taught all who connected with him.

In the AJO tribute to him at his 70th birthday, letters from colleagues discussed these personal attributes. An example from Fred Jakobiec, MD, “His personal and professional lives have been a parable of strength, decency, and accomplishment.” And, my sister, Barb, “Whether it be an awesome performance as third baseman or winning a tennis match or the honor of another professional award, his humility has always amazed me.”

At a time when he received a string of awards, his young granddaughter asked, “Cool Papa, I forgot, what made you so famous?” He answered, “Because I’m your grandfather, Lauren.” This was Zim as we knew him.

Editor’s Note: Mary Louise Z. Collins, MD, is an Academy trustee-at-large and chair of the Department of Ophthalmology, director of pediatric ophthalmology and strabismus, and director of resident education for the Ophthalmology Residency Program at Greater Baltimore Medical Center (GBMC) in Maryland. We are grateful to her and our History of Ophthalmology editor, Daniel M. Albert, MD, MS, and his editorial assistant, Ms. Jane Shull, for contributing this article to Scope.