The boxing adage that “father time is undefeated” can easily be applied to ophthalmologists. At some point in our careers we will need to decide if we are desirous and/or capable of continuing to practice our specialty in full or in part.

For some, health conditions and personal economics may be the deciding factors to stop or continue, whereas for most, the decision and timing will be elective. No template matches the needs or plans for all, as most situations are very personal and to some degree emotional.

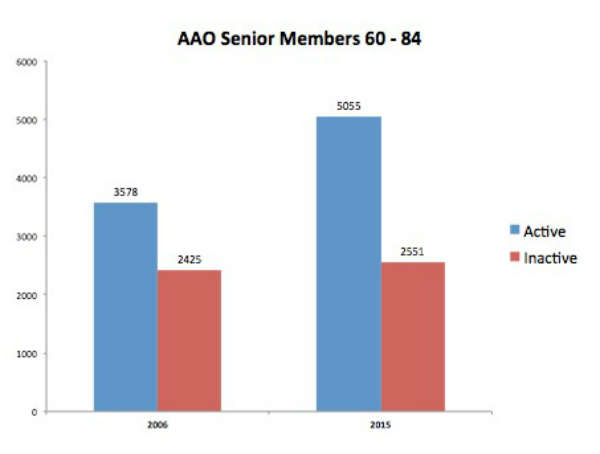

Figure 1 – Proportion of Academy SOs active in 2006 and 2015 (courtesy of Harry Zink, MD, and the American Academy of Ophthalmology).

The typical physician prepares more years, works more hours and is more invested in his/her career than are most other professionals. Many of us tend to consider our professional life as our lives. We might have fewer hobbies and “outside interests” than people in other professional groups.

Given good physical and financial health, physicians often prefer to taper our workload in stages, affording more free time and less responsibility while not “cutting the cord” abruptly.

Understandably, we face many facets to the process as we prepare for and learn to accept our “seniority,” both personally and professionally, just as we hopefully learned to accept the dreaded “Senior Ophthalmologist” ribbon when registering for the Academy annual meeting.

Consider the following dialog. Upon visiting a colleague (let’s call him Ted) who was well into his 70s, I noted a new physician’s name on his door.

Masket: “Ted, are you planning a partnership?”

Ted: “Nah!!”

Masket: “Then what is your exit strategy?”

Ted, without batting an eyelash: “Death!!”

One might consider his response an extreme form of non-exit strategy, but in fact, his plan will lead to an abrupt exit.

While I did not find his strategy an appealing one, there are several non-exit or gradual exit pathways ophthalmologists can consider. These include reducing work time or services, discontinuing or transferring their current practice, working for industry, working for health plans, working in a university or VA setting, doing volunteer or mission work, etc. Much of what follows I’ve garnered from the presentations of colleagues during Academy annual meetings.

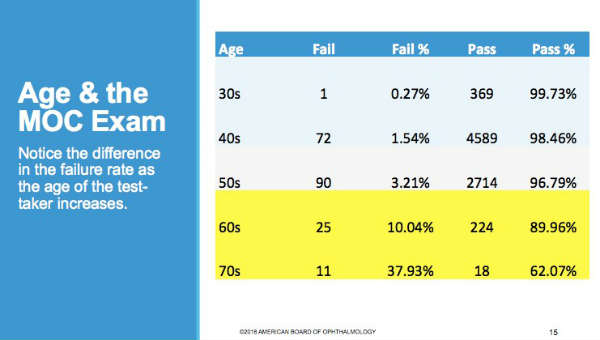

Figure 2 – Failure and pass rates over varied age groups show lower success rates for older ophthalmologists on DOCK exam (courtesy of John B. Clarkson, MD, and Meghan McGowan, American Board of Ophthalmology).

Ophthalmologists Working Longer

Academy surveys of senior ophthalmologists (those 60 and above) indicate that, as a group, we tend to stay active longer than our predecessors. Presently 50 percent of SOs aged 76 are professionally active in some form; 10 years ago, the 50 percent active mark was true for those of us age 71. In fact, nearly 25 percent of the overall physician work force nationwide is of Medicare age.

As you can see in Figure 1, the number of Academy members ages of 60 to 84 who consider themselves to be active rather than inactive has doubled from 2006 to 2015.

Age and continuing education

One concern of staying “too long” is erosion of manual and cognitive skills. Certainly, we are susceptible to age-related diseases and degenerations. American Medical Association research also suggests that physicians over age 60 are less likely to acquire new knowledge and skills over time, although they may retain their existing knowledge base. Indeed, American Board of Ophthalmology data show that older ophthalmologists have a declining pass rate when taking the Demonstration of Ophthalmic Cognitive Knowledge exam for maintenance of certification (Figure 2).

The ABO encourages all ophthalmologists to participate in the MOC process to keep their knowledge base current. In some circles (i.e. hospital credentialing), people have called for mandatory evaluation of physician competence beyond certain ages, in similar fashion to airline pilots. However, others also consider such policies discriminatory. Some European centers mandate surgeon retirement at specific ages.

Does age affect surgery?

A related and common concern is that surgical complications may rise along with surgeon age. Indeed, fear of complications and difficulty adapting to ever-emerging techniques and technologies induces some ophthalmologists to “slow down” by stopping surgery but continuing in a medical role in the same practice setting. Following a major coronary infarction, a colleague discontinued surgery, likely prolonging his life and his occupation.

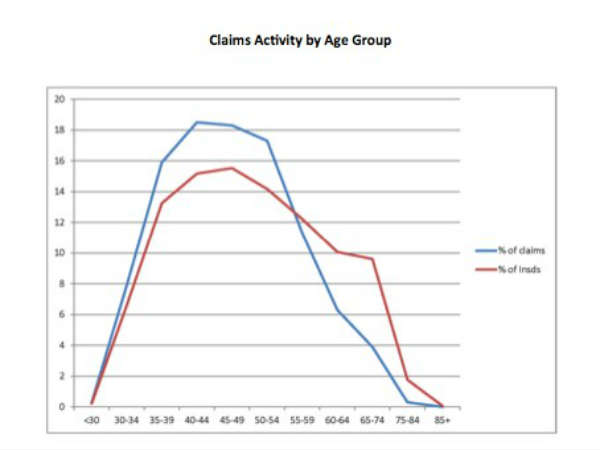

Figure 3 – Curves show similar patterns for claims made against ophthalmologists and age distribution of insureds (courtesy of Harry Zink, MD, OMIC and the AAO).

However, OMIC malpractice data on claims versus surgeon age (Figure 3) shows that the number of claims correlates well with the percentage of insured surgeons. Put another way, only 10.5 percent of OMIC claims involved surgeons between 60 and 85, while that group accounted for 21 percent of those insured.

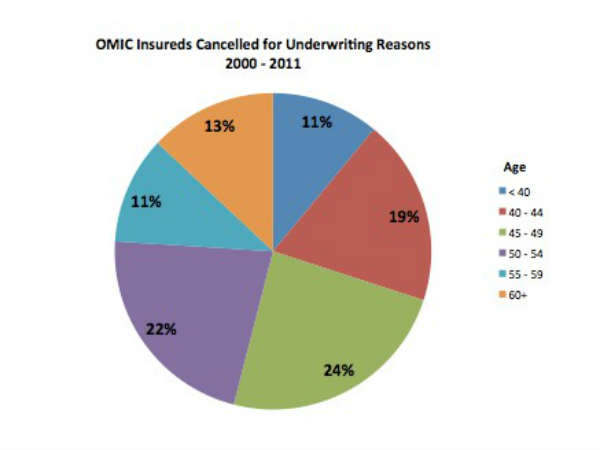

Nor does OMIC drop insured ophthalmologists for underwriting purposes as they get older. Figure 4 shows that only 13 percent of dropped physicians were over 60, although over-60 ophthalmologists represent 21 percent of those insured. In sum, it appears that ageing surgeons do not experience greater malpractice claims. Perhaps this reflects better judgment regarding case selection, etc.

Changing roles

All that said, one must accept that stopping surgery may reduce your self-esteem. As one colleague said, in another sports analogy, quitting surgery can be like “going to the bench after being the starting point guard.” Nevertheless, the reduced stress and responsibility can and hopefully will positively balance the change.

Figure 4 - Age distribution of OMIC insureds cancelled for underwriting purposes (courtesy of Harry Zink, MD, OMIC and the AAO).

Each of us must determine when it is appropriate to make that move, always keeping patient safety first in our minds. It is prudent to ask a colleague to observe surgery first hand or review surgical videos and objectively comment on one’s skills.

Some physicians adjust their work routine by sharing the practice with a new colleague, each working a month, a week or what have you, while the other takes the equivalent time off. This approach lets the doctor get a sense of life absent work and find new opportunities and interests, both inside and outside the profession. At the same time, it protects the practice from economic disruption, as it will be staffed full time.

Gradual reduction of work time and practice responsibilities seems to offer the best opportunity for many physicians in transition. However, one must also look at the business-related impact on the practice. The practice must remain structurally and financially viable while transferring ownership, workload and responsibility from the senior principal to others.

How change affects your business

Among the issues to consider is office space; can existing or new doctors fill the office lanes? The same holds true for office staff: will need for their skills remain the same or will some accept fewer work hours? New physicians may also need mentoring and assistance in filling their schedules.

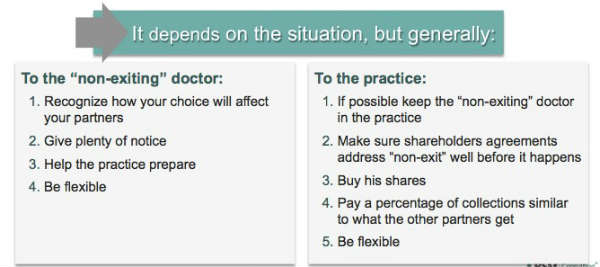

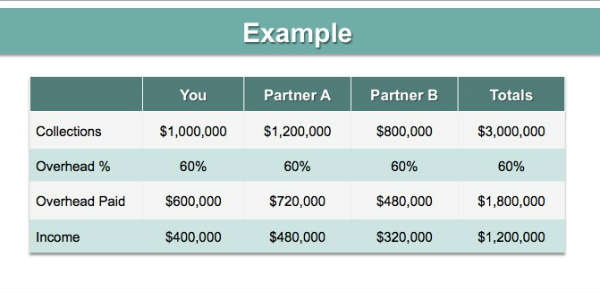

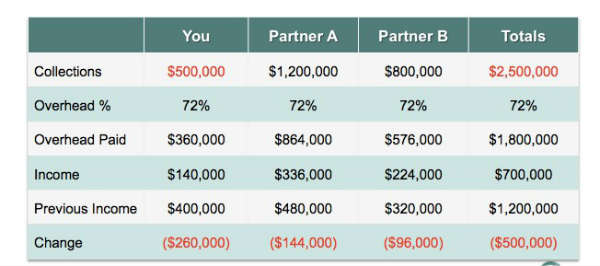

Regardless of the practice situation, one guiding principle is flexibility (Table 1). Without doubt, the projected change will affect compensation for all physicians in a practice. You will need to adjust accordingly, unless you can shift the workload from the “slowing down doctor” to others. Tables 2 and 3 show the possible financial consequence should the principal partner reduce workload without reducing overhead or having other practitioners increase their workload.

In my own case, I brought a colleague into the practice 10 years ago. As she rapidly proved her mettle, I sensed that she could and would succeed me over time, allowing a very gradual strategy — not at all like my friend Ted’s plan. After two years, we formed a partnership that allowed us to share revenues in part by production.

Five years ago, at age 70, I resigned from all insurance carriers and reduced my workload to three half days per week. That decision enabled me to continue to practice, perform surgery and generate adequate revenue while shifting the bulk of patient care to my partner and the other doctors in the practice.

Now, at age 75, I have voluntarily discontinued surgery, reduced my workload further and transferred practice ownership, while mentoring a young physician and introducing him to my patients. The most recent change has allowed me to devote time to training, to our Foundation and to the research arm of the practice.

Table 1 – Suggested approach for a gradual non-exit strategy with regard to practice-related business concerns (courtesy of Derek Preece, MBA, and BSM Consulting)

Table 2 – Income and expense flow chart using example where “YOU” is the physician about to reduce workload. (Courtesy Derek Preece, MBA and BSM Consulting)

Table 3 – The financial impact on a practice when physician YOU reduce workload and income by 50 percent without shifting workload to other practice members (courtesy of Derek Preece, MBA, and BSM Consulting).

Thanks to Amir Arbisser, MD; John G. Clarkson, MD; Meghan McGowan of the American Board of Ophthalmology; William Fishkind, MD; Derek Preece, MBA, of BSM Consulting; Paul Orloff, MD; and Harry Zink, MD; for their contributions to this article.